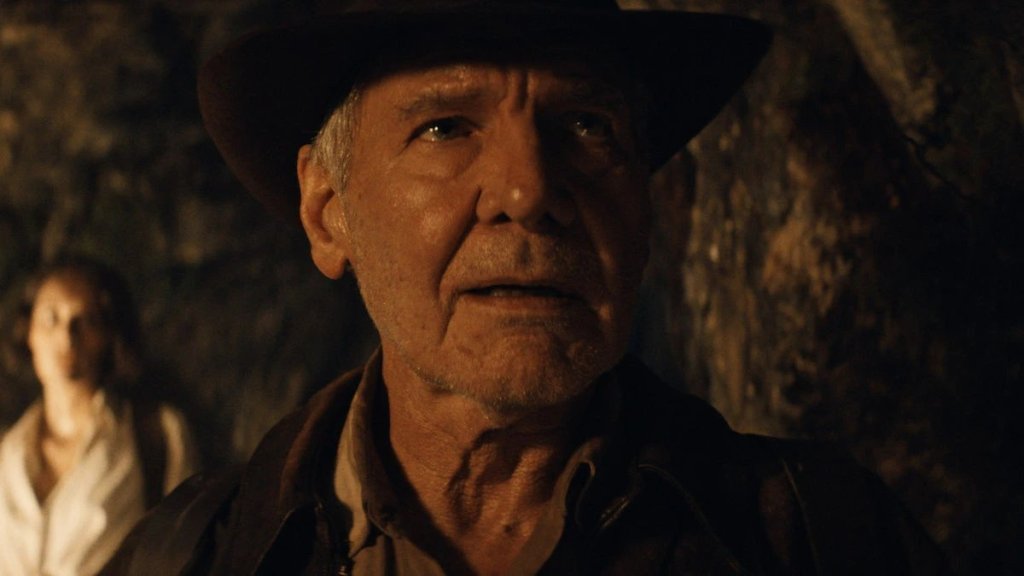

Chicago film critic Josh Larsen notes in his review of the recent Indiana Jones movie, Dial of Destiny, Mangold’s interest in demythologizing Indiana Jones He strips away the hero’s storied past and creates the necessary space for exploring who this figure is and what he is all about in light of his story seemingly coming to an end.

Where Indy was once romanticized and idolized as the young teacher inspiring bright minded students to engage with history, now he is all but ignored by a class of fresh, bright eyed students shoving him aside in favor of a “new age” of exploration. The hero has seemingly been made irrelevant by progress, his aged, shirtless body sitting in stark contrast to the fully clothe and deaged relic of the past. For the all the adventures Indy has experienced, it seems aging in the midst of an ever changing wold is too great of an opponant to overcome.

As Josh notes, the film is about time, and your place in time, and further yet “the appropriateness of your place in time”. Jones is resisting all the forces that are threatening to “move him ahead in time” while giving in to a pesistant cynicism regarding his life an this world at the same time. His typical ornery an disgruntled persona finally suits his circumstances, in a nearly poetic fashion. On the larger level of the mythos of Indiana Jones, what hangs in the balance is “his relationship to us and to the world” today.

As mentioned, Jones has always been something of a cynic. Someone who is constantly battling against the nature of his experiences, which threaten to undermine the safety and certainy of his reasoned and compartmentalized understanding of reality, as an academic and historian an as an adventurer. Such existential and theological crisis are apparent throughout the series, surfacing in different ways and in different forms. In a sort of penultimate statement, all of this angst comes to a head when Jones confesses in Dial of Destiny, “I don’t believe in magic. But a few times in my life I’ve seen things, things I can’t explain.” How does he manage this in the face of his commitment to reason? He goes on to say, “I have come to believe its not so much about what you believe, but how hard you believe it.” What is interesting about this statement is how Jones applies this to time itself. To the reality that who he is in the world no longer seems to matter or hold significance. This is, I think, what forms the existential crisis in Dial of Destiny. Does his strength come from resisting the truth of his aging by believing he still has significance, or does his cynicism hold more power when it comes to recognizing he no longer has a place in this world?

If Jone’s passion for history rings true, what seems abundantly clear is that he now finds himself wondering whether his own history had any worth at all. The question “does the past matter” and the subsequent question “does my past matter” seem inseperable when it comes to weighing a world defined by inevitable progress. On a more meta level, the film wonders about a world that no longer seems to have room for Indy and this franchise as well. What the film lingers on and lets perculate, is the idea that Jones has finally given up. He has to reckon with “who he is now, and whether he wants to be a part of this world”, as Josh surmises. Late in the film this point of crisis comes to a head when Jones literally wants to stay buried with the past, faded from the world’s consciousness. Given the mythology of Indy, this seems fitting. Given the demythologizing of Indy this seems tragic. As Josh Larsen suggests, “It’s okay for him to be done.” But even as we say this, something about this statement feels to be not quite right. In truth, if we do say this, we must then wrecken with where this character goes when his time has come and gone and why it mattered at all. Lest we think we are immuune to such things, those of us who grew up with Indy then become bound to the same fate and to the same point of crisis. Who is Indy becomes a question that then gets turned in on ourselves: who am I. A question that we can dial up even further in the grander scope of this film: what then is the meaning of existence.

It is not dealing with a “dial”, not unless you count the internet in a post dial up world, but Celine Song’s much celebrated indie film Past Lives also happens to be dealing with some of these questions as it explores matters of destiny. As the official synopssis outlines: Nora and Hae Sung, two deeply connected chilhood freinds, are wrest apart after Nora’s family emigrates from South Korea. 20 years later, they are reunited for one fateful week as they confront notions of love and destiny.

Through this contemplative and richly thematic exploration of our relationship to time and to the passing of time, Celine Song pushes us as viewers to think about our lives in terms of story. The motif of past lives is functioning on multiple levels within the film, digging underneath the what if’s of all our past choices and potentialities, all of which intersect with the different moments, people, possibilities and actualities inherent in the story of our lives. Song seems to differentiate the stories that we are given by way of living in the present time from the stories we tell outside of time by way of the past. The now that we occupy brings us into relationship with all of the past that has brought us to where we are, making memory less than static as a function. It develops. It grows. It emerges within our storytelling. It can help us to mark one path from another, even as these paths are ultimately connected and bound together, the ones we take and the ones we diverged from. We are different things to different people, and within this hangs all the myriad sides of lifes pontentiality, be it realized in the now or lost in time. There is a real sense that hidden in the passage of time is a deeply rooted anxiety regarding the possible lives that have indeed passed us by, leading to an inate sense that the story we are living now is the story we have, and yet how we make sense of this story in light of the past is a much harder notion to wrestle down. How do we keep the story we are occupying in the now from locating its true measure in the stories of our past. This question seems to be, in a very real way, at the root of how it is we figure out this thing we call a life.

This blogspace was birthed out of my own existential crisis over turning 40. As I’ve written a few times over, this was a real dark point in my story. The story that I was occupying at that time felt deeply uncertain when I set it in relationship to my past. If I’m honest, I’ve made efforts to recover, but I’m not sure how far I’ve actually come. With every new year my experience of turning 40 becomes more and more indebted to the past, the story of now more and more freighted. That is how this life seems to go: forever forward with the baggage in tow, leaving us only with the uncertainty of the now.

Perhaps the more difficult thing for me to process is that these ruminations reach far beyond “my” place in this world. Not unlike Indy, these personal questions tend to push further into questions about the nature of existence as I wonder about whether this world still has room for “me” at all. Much harder to reconcile is the idea that so many of the things that once made this world matter, things that my younger self would have insisted were necessary to the now, no longer do. Opinions. Knowledge, Truths, Pursuits, Convictions, Investments. Experiences. Many of these things have become relics of a story now lost to history, in danger of at least feeling like they are becoming increasingly given to insignificance and irrelevance as time pushes forward. In truth, in my most cynical an struggling moments, this raises serious questions about what truth an reality even is. The longer I live, the more I find myself living in a world that I no longer share a language with, the past erasing the necessary lines of communication that can enable me to live into the now with much significance and clarity. And the more these feelings surface, the more I tend to retreat into the handful of equally fading relics that surround me, feeling like a passive observer stuck in time as the world grows narrower and narrower.

Perhaps this is what makes the ending of Dial of Destiny so poignant for me personally. Not because it answers this point of crisis directly, but because it locates the singular space where we are able to wrestle with such feelings and thoughts. Its no accident, in classic storytelling form, that this singular space is the very thing that ties the ending of Dial of Destiny back to its beginning: the relationships an experiences that hold this world together with some semblance of meaning, however illusive it might become. The journey Indy takes towards recognizing, or perhaps reconciling, when his story definitively goes from one that is “being told” to one “that is finding its completion” is worth reflecting on. Attached to this is Past Live’s exploration of a similar and parallel process, linking this quesetion to the increasingly narrowing gap that exists between our present potentiality and its gradual loss. The more time pushes forward the narrower this gap becomes, begging the sorts of questions that we find surfacing in Dial of Destiny relating to Indy’s aged self navigating an unfamiliar world: How long do we fight to stay relevant, and when does time begin to pull us back into the past and tell us to stop. This has real implications for how we navigate the now, especially when we begin to attach this to questions about truth and meaning.

That poignancy surfaces for me all the more as I face down 47, my birthday having just passsed me by on August 4th. If my 40 year old self imagined my story 7 years later I’m not sure if its the cynicism or the optimism that wins out. I’m not sure which belief is the strongest, and likely that changes day by day, week by week. As my 47 year old self, the one who occupies the now, reflects on the past 7 years, I’m not so certain I know what to do with this story, especially as I think about the ever narrowing gap of between my own potentiality and the loss of it. The only thing I can say with confidence is, something sustained me. I was 40. Now I am 47. And if I look hard enough there is a story to tell, and maybe one worth telling. And the more days I live, the more need there is, I feel, to reflect on both sides of that story, spending less and less time on the now and more and more time on the past that led up to the now. Which of course feels antithetical to how I was always taught to live: in the now. This is why such ruminations are a fearful and uncertain exercise, to be sure, as such truths leave me uncertain about the power of the now to shape my story. As I continue to wrestle with my anxiety surrounding the act of living in the face of my own aged self, the past has a way of unsettling the things that seem important to me today. And I don’t know if that is a defeating thought or a liberating one.

Thinking about Celine Songs film though, one thing that seems to unsettle that picture for me is this: as long as I’m reflecting I’m still living somewhere. On my best days I can relate to Indy’s dilemma. I get the past. In many ways I feel like I belong to the past. It is a story I know and know well. This is my mythology. Am I fooling myself into thinking that this story matters? Those are the doubts that anxiety fuels, and the reality of the now and its unfamiliar terrain has a powerful tendency to stoke these flames. The world can be a lonely place when you can’t speak its language and when it seems to have little to no interest in learning yours. This is just the honest places that my mind sometimes goes to when I confront these yearly markers. And yet, as Past Lives seems to suggest, time is not a concept that can make sense of the problem of infinite regress on its own. That’s why it attaches itself to the passage, to the idea of beginnings an endings as a conception that our minds can handle in the now. But Song never lets that cannibalize the nature of reality itself. She leaves room for mystery to weave its way into the tendency to comparmentalize and rationalize our experiences away. Likely for the same reason Indiana Jones can’t simply rely on reason alone: because he’s experienced things. Things he can’t explain. If we are being honest, I think we all have. And often it is that mystery that sustains us, even if it is against the powerful efforts of our cynicism to undermine it. That’s not always enough. On August 4th I wasn’t convinced it was. But today is different, and for now that’s enough.