Rewind to summer 2022. More than a little stir crazy from a prolonged pandemic, borders had finally begun to swing open, offering us an opportunity to go somewhere. Anywhere but here was the mantra. After some time deliberating, we ended up in Oklahoma City. Why Oklahoma City is a question we would be asked more times than we could count. If I sat down to explain the path to this somewhat obscure, mid-western escape, I promise it would make sense. It just became easier after a while to reduce it to a simple “why not”.

Summer 2023. Once again in deliberations, this time staring down potential flights to England as they jumped to an average price of $1500. Where to go when prices are literally sky high. We already had an early trip to Milwaukee planned around a concert, but it is a long summer- rest assured that’s not a complaint- and for as much as I love that Wisconsin cheese I was craving something more substantial.

As the summer days whittled away, so did potential ideas and options for getting away. We had some potential pieces on the table, but no significant agreement and even less that made practical sense to necessary budget travelers like us. The closer we got to the start of a new school season, the less desirable it was for Jen to venture too far off the beaten path. That’s when the idea of a potential solo trip came to the table.

Full disclosure: I had never travelled by myself before, so this was a first. I wasn’t sure how I would feel about the experience. But we started the initial thought process. Where is somewhere I would like to go that Jen has little interest in? What were the parameters?

Sky high prices continue to rule out overseas. Local flights to particular North American destinations were within reason. Places I can drive to even more reasonable. One place that had been sitting at the top of my list was Charleston, South Carolina. It often finds itself in the fray of travel magazines and site’s top places to visit from year to year. I love the ocean. There was intrigue over the history and its stated old world charm. Considering that late August would put it in the thick of that southern, summer heat, such an idea was an immediate write off for Jen.

That’s when some other potential pieces started to fall into place. I had just started reading the recently released biography by Jonathan Elg on Martin Luther King.

What about taking those other southern states and turning that into a kind of pilgrimage? Giving the biography some boots on the ground context? Birmingham and Atlanta weren’t exactly on my radar in terms of potential travel destinations, but the more I reflected on its potential the more it seemed like a perfect fit for a solo venture.

Plans started to take shape and a last minute late summer escape came into being.

Along the way- and yes, for anyone wondering, this budget traveler did decide to drive the 2300 kilometer stretch to Birmingham by myself- I used the time to reflect, making my way through Elg’s biography. As I went along, the story of MLK turned into the story of America, and in many ways began to form into a cross-cultural movement from my own context into another. That last point is significant to me. I recall the moment this really hit for me, sitting just outside the doors of the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church on Sunday morning, the day before the anniversary of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech an historic march.

Borrowing from the story behind the album, DJ Khaled’s album God Did, the preacher used Ezekiel 37:1-14 as a way to tie the story of Israel to the story of King to the story of the Black experience, to the story of the Black experience in Atlanta, to the story of Atlanta, to the story of America, to the story of the world, and ultimately to the story of me an you.The message walked through these following observations and questions:

Something happens when God changes your viewpoint from high to low.

“The hand of the Lord was on me, and he brought me out by the Spirit of the Lord and set me in the middle of the a valley; it was full of bones.” (Ezekiel 37:1)

Can these dead bones speak?

“Son of man, can these bones live?” (37:3)

Surrounded by death, do we believe in the power of the resurrection?

“So I prophesied as I was commanded. And as I was prophesying, there was a noise, a rattling sound, an the bones came together, bone to bone. I looked, and tendons and flesh appeared on them an skin covered them, but there was no breath in them.” (Ezekiel 37:7-8)

Do we believe we have this power?

“Come breath, from the four winds and breathe into these slain, that they may live… these bones are the people of Israel. They say, Our bones are dried up and our hope is gone; we are cut off. Therefore prophesy and say to them: This is what the Sovereign Lord says; My people, I am going to open your graves and bring you up from them; I will bring you back to the land of Israel…. I will put my Spirit in you and you will live, and I will settle you in your own land.” (Ezekiel 37:11-14)

The phrase that binds this portrait together as a picture of hope is this- “Then you, my people, will know that I am the Lord” (Ezekiel 37:13). If you read further in the passage this connects directly to the idea of God’s faithfulness to the covenant promise. Even in the midst of dry bones, God makes an “everlasting promise”, a “covenant of peace” (37:26). A promise that “God’s dwelling place will be with them”, these raised up bones, and “I will be their God, and they will be my people.”

I came into this service still shaken from my time visiting Birmingham/Montgomery/Selma.

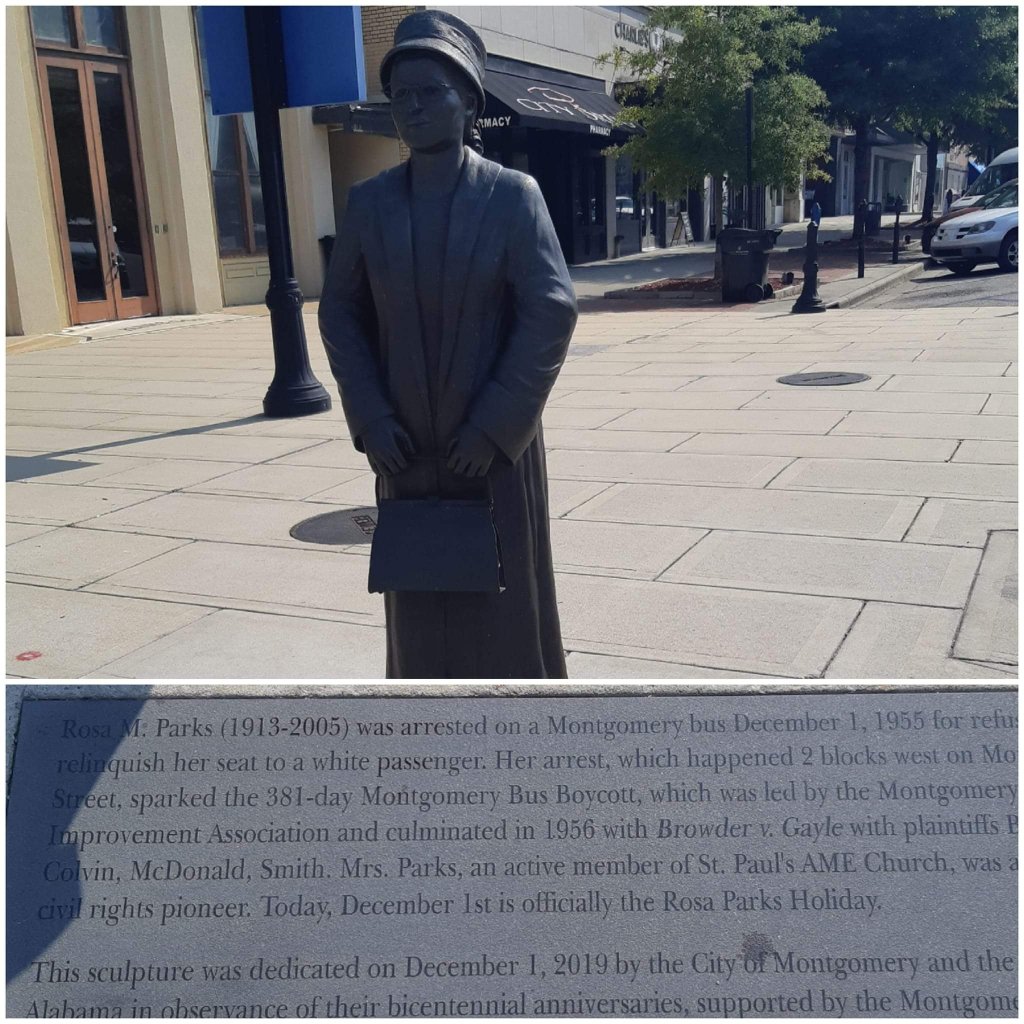

If there was one thing I was struck by, and to be sure there were many revelatory moments, standing in the spot where Rosa Parks boarded that bus, traversing the path of the freedom riders, walking the Edmund Pettus Bridge, or experiencing the EJI’s (Equal Justice Initiative) incredible museum and memorial, it was just how much of a cross cultural movement this was for me. As a Canadian I tend to encounter two primary responses to things going on south of the border. Either I encounter those who, on the grounds of Canada’s tendency to major in American history and minor in our own, want to distance our story from theirs claiming full understanding of what that story is, or I encounter those who want to shine on a light on the story of black discrimination north of the border, resisting those moves to distance ourselves from the problem.

And yet what became clear to me was, this is not my story. This is not Canada’s story. And the story I thought I knew was not the one I encountered. Not unlike the sentiments in an opinion piece on the anniversary of the march on washington penned by Jamelle Bouie for the New York Times titled The Forgotten Radicalism of the March on Washington, it was clear how easy it is to reduce the civil rights movement to a quick list of popular touchpoints, kind of like a tourist hitting all the necessary sights. And yet, as Bouie points out, “less well remembered… is the fact that both the march an King’s speech were organized around much more than opposition to anti-Black discrimination.” Bouie goes on to say that the “march wasn’t a demand for a more inclusive arrangement under the umbrella of postwar American liberalism… it was a demand for something more.- for a social democracy of equals, grounded in the long Black American struggle to realize the promises of the Declaration of Independence and the potential of Reconstruction”, defined as they were by the official ten demands given to Washington.

Which is to say, this is a distinctly American story with an American context and a very real concern for the oppression that existed an exists on American soil. Which is also to say- this is not my story. This is not the story of Canada. Canada has its own story. If I am to know this story I must resist the tendency to make the story synonymous with my own.

And yet, as the sermon that Sunday demonstrated, it is at the same time a story that is not contained to such boundaries. To hear and to learn how the Black experience approaches an applies the story of Israel, for example, is to invite me to consider how I read the same story from my own vantage point. For me, the a portrait of a prophet speaking to an enslaved and divided nation, offering a word of hope to those dry bones, who are being raised up and given power to enact change and declare liberation, was an invitation to know this same God in my own context. standing as I was on the outside looking in. To know that this story is not simply about an oppressed people being afforded liberation and life, but that such liberation and life comes with the invitation to bear witness of this knowledge of God to the whole world is the thing that invites me in as a participant.

Talking to one Atlanta resident prior to the service, I noted how the weight of my experience in Birmingham, Montgomery and Selma, an experience that evoked similar emotions to visiting Auschwitz, contrasted with the hopefulness that I felt travelling this path from King’s childhood home and boyhood neighborhood to his final resting place and Church. There was something in the air here that helped turn immense tragedy to life, even in a climate where, as the sentiments they shared seemed to echo, the dry bones of this present moment felt more like witnessing to zombies wandering around in a zombie land (to borrow the language of the preacher).

Right before I left on my trip someone sent me a timely article. It was also from the New York Times, and it represented two different opinions on the subject of travel. In one article, penned by Agnes Collard titled “The Case Against Travel”, the general sentiment was that “travel turns us into the worst versions of ourselves while convincing us that we’re at our best”. The target of this sentiment was this- travel as a status symbol. This can equally be applied to being well read or well educated. Collard conjures up the great philosophers of the past and contrasts them with this emergent idea called “tourism”, locating the greatest ideas and most fruitful accomplishments in those who disdained the idea of turning other places into shrines. When we are at home we tend to avoid touristy spots like the plague. When we travel, touristy spots become the portrait we find of places not our home. And the only thing travel really tends to foster are people who love to talk about their travels and those who hate to listen to travellers talk. As the writer puts it, “forms of communication driven more by the needs of the producer than the consumer.” The primary question becomes this: “(One) might speak of their travel as though it were transformative, a once in a lifetime experience, but will you be able to notice a difference in their behavior, their beliefs, their moral compass? Will there be any difference at all?” And then they pose this question:

“Imagine how your life would look if you discovered that you would never again travel.”

Collard suggests that what would become immediately clear is all the ways in which travel functions as an illusionary practice breaking up the monotony of life in a singular place, “obscuring from view the certainty of annihilation.” And just to dial this down even more, Collard accentuates this with the following sentiment: “You don’t like to think about the fact that someday you will do nothing and be nobody. You will only allow yourself to preview this experience when you can disguise it in a narrative about how you are doing many exciting and edifying things…. Socrates said that philosophy is a preparation for death. For everyone else, there’s travel.”

Ross Douthat penned a responsive opinion piece to this article titled The Case For Tourism: “Community and Sublimity on a European Vacation”. He sums up his opinion in this way.

“Seen clearly, one might argue, the entire world is shot through with majesty, which is why the perfectly enlightened need never practice tourism. But there are places where the sublimity is especially strong… Going in search of such places is no substitute for seeking deeper forms of conversion an communion. But neither is it just a detour or distraction from those obligations. The sublime justifies itself.”

I had these dueling think pieces lingering in the back of my mind for most of my trip. I wondered about what the sublime means, what enlightenment means, what it means to distinguish between a traveler and a pilgrim or even if we need to, and how my own sense of wanderlust relates to this. For me I returned, as a I typically do, with a greater appreciation for my home. But I also returned with a greater awareness of what travel means for me- it broadens my world. It broadens my awareness of the world. It helps me to see how this place I call home is indeed a microcosm of the bigger picture of this story we call the world, one pertinant an aware with its own particularities and questions.

One of the things that Elg’s biography did, being the first to incorporate the recent release of a mountain of information and documents along with testimonies of eye witnesses now free to speak this many years later, is demythologize King in the public eye. He was a complicated human with very real shortcomings. And yet it is in the demythologizing that we are able to see the true power of his accomplishments. As travelers, we romanticize the places we have not been to and have not seen. To traverse these places is to have them stripped of their mystery and cast in a new light. The real question becomes, is a demythologized figure someone we can still find wonder in? Is a demytholgoized place somewhere we can still find wonder in? The true worth of travel for me is its ability to encourage us to do just this. To recover the sort of wonder that is willing to reclaim the mystery of the myth in a world that threatens to redefine these stories as mere illusion. The problem with demythologizing is that things like wonder an hope tend to be tossed out the door as well. And yet thats not what I experience in the doors of this church. Rather, what I found was an inate desire to allow the God known in the demythologizing of these dry bones to reveal the greater reality of the resurrrection, hope in a world often thrust into darkness. In this sense the myth becomes a truer representation of their reality. In this sense travel opens us up to a greater awarness of the world and its genuine mystery an wonder. That we can appreciate and enjoy the art of good travel at the same time- good food, good sunsets, the joy of an ocean front, good company, interesting and awe inspiring sites- is simply part of the wonder.