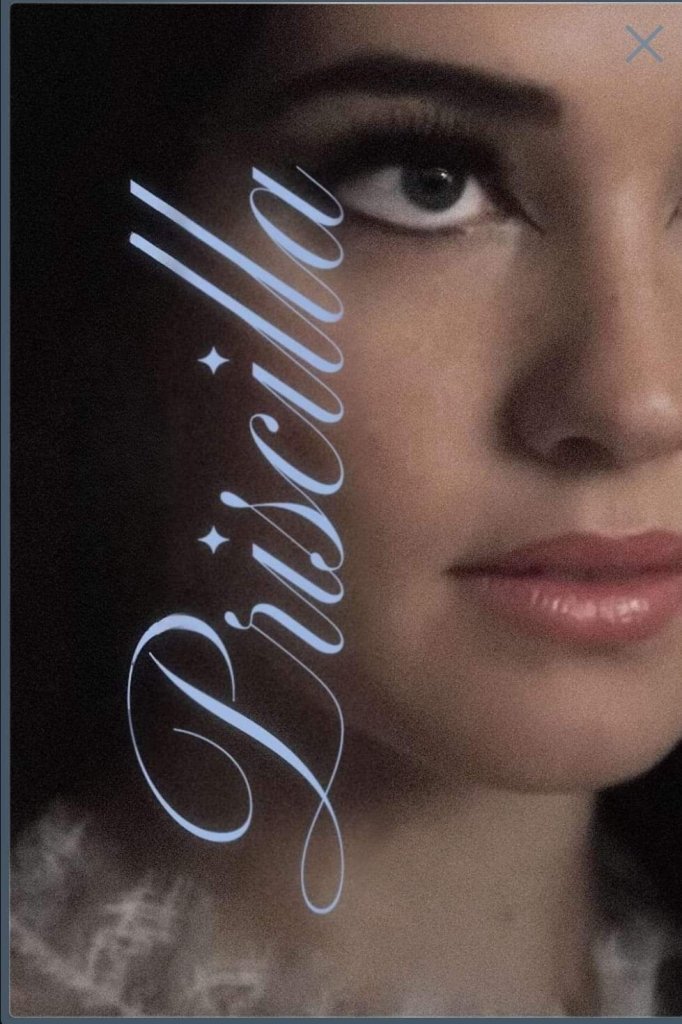

Film Journal 2023: Priscilla

Directed by Sofia Coppola

One of the things that Sofia Coppola’s films tend to ask of viewers is to expect to have a complicated relationship with an iinitial viewing, but to also trust that subsequent viewings will ultimately bring the pieces together in a coherent fashion. She is not prone to catering to easy tricks of the trade or telling simple stories. Often her films will create a dance between certain genre placements and narrative approaches (biopic/character study) while using metaphor and allegory to become something else entirely. This has a tendency to create certain illusions within the experience, while simultaneously allowing those illusions to challenge ones perspective on both the subject matter and its aims.

One of the tools Coppola uses to achieve this is a willingness, or tendency, to play around with a scattered narrative. In Priscilla, part of the ebb and flow of the film is its abrupt editing, alluding to things and then never showing or addressing them, randomly jumping forward for unknown reasons at different times. And yet this scattered sense is part of what allows those identifiable arcs and themes to take root in far more subtle ways, emphasizing certain scenes and shots and moments as a means of redirecting our attention towards what the Director really wants us to see.

Priscilla of course comes on the heels of the extremely successful release of Elvis last year. The two films couldn’t be more different in style and approach, but this actually sets them up to be a perfect compliment to their different points of perspective. Elvis sees the story of Priscilla from Elvis’ perspective, and what’s super interesting to note is the positive light he places Priscilla in and the weight of the blame he places on his own shoulders for their eventual decline. In Priscilla, Coppola identifies Priscilla as the one with a rise and fall arc, bringing into the mix questions about her own self blame for the situation she finds herself in. One big difference as well, is that while Elvis uses its arc of the famed singer to evoke a degree of empathy for his downfall, in Priscilla there is no other surrounding characters on which to place culpability and blame, such as the agent who is manipulating things in Elvis. The figure of Elvis is presented in an even worse light in Priscilla, identifying again the differences in perspective. Two people telling the same story from different vantage points, and it results in partial pictures that gain their fullness when brought together.

The frenetic, mile a minute depiction of his dramatic rise and fall in Elvis is contrasted directly with Priscilla, who sees Elvis primarily in the context of Graceland, out of sight of the craziness of his public life. What she knows of that side comes from the media and newspaper clippings and magazine articles. Thus when Elvis leaves, her life essentially submits itself to the slow, mundane realities of a life now confined to the gated premise of an empty Graceland. What this results in is a film where the action takes place largely within the internal transformation of its lead. One might be tempted to say this is ultimately a transformation from innocence towards its loss, and from idealistic young woman with the world seemingly at her doorstep to enslaved housewife with all sense ot agency effectively stripped away. But I actually think it’s not quite that straightforward. She’s not presented as innocent as it might first seem, and the things driving her towards this singular obsession feel largely undefined and complex in nature. The film raises interesting questions regarding her manipulation of her parents and Elvis’ manipulation of her parents, quietly attaching this to these moments in the film where the power dynamics between themselves ultimately shift back and forth within the dynamics of their relationship.

One of the great things about Coppola’s choice here is that this is a larger than life story about larger than life characters that seems to tell a story that anyone could find themselves in. Coppola does some really interesting things with the way she crafts this film, using the absence of Elvis’ music and the absence of his performances, save for a momentary television segment and a brief backside shot (the way the film captured the quiet and subtle interactions between the two of them in this moment was cinematic perfection) to play this as a relationship drama. And one of the things I latched on to, and it’s one of the more subtle and sub-textual elements to be sure, is the way it depicts the relationship between Priscilla and her parents. Anyone who has ever had the experience of wanting to protect their child from the potential consequence of certain decisions, but where they also know that child is going to make the decisions they have settled on no matter what, I think can find something in this part of the story to connect to. The parents know somethings not right, even outside of the 10 year age difference between Elvis and a young woman in grade 9, and yet they also know that that she has made up her mind and they have lost all point of influence on their daughters decision. They are up against a much more powerful force. And while the film leaves no doubt that this force at least in part lies in the powerful enterprise that surrounds Elvis, Coppola smartly writes in these subsequent observations about how it is that we understand liberty to begin with. Part of what Priscilla is clearly chasing after is an illusion of liberty, and what becomes unmasked is the power of those worldly draws- sex and power being at the forefront, to frame this illusion within an inescapable draw. This blurs the line between liberty as “the right to be and do what I want”, and the ensuing question that emerges from the idea that we are all always shaped by some external force over our lives. And certainly this adds to the complexities of what it is that drives her into this relationship to begin with. We never do see any sort of reconciliation with the parents, so that is left in the air for us to consider, but it is a part of what makes Priscillas innocence or lack of it difficult to define.

It might sound odd to say this too, but even with all that, somehow Coppola manages to evoke this sense of the evil forces that hold this relationship in its grip, imploding it bit by bit, without ever completely condemning the relationship itself or the persons themselves. We will no doubt make our judgments, as the film invites us to do, but it steers clear of making them on it’s own. It’s a fascinating way to hold the two things in tension, making for a film that is filled with the Directors sensibilities while possibly being her most mature effort to date.