I have a confession

Back in June I decided to join a number of facebook atheist debate/discussion groups. The words debate and discussion being contained to a necessary air quote variety of terminology.

As a few of my friends noted upon vocalizing my confession- “everyone’s got a calling I guess.” I’m still trying to parse out whether these were words of judgment or absolution.

In any case, I knew what these spaces were before I joined. I guess I now know what they still are. They represent the lowest form of rational discourse (proof arguments), they obsess over uninteresting questions and demands (can you prove a god exists), and every post follows the same inevitable pattern- two sides calling each other idiots until one or both block the other.

I knew this. I know this. And I got sucked right back into it. For 6 straight months. I’ll be honest- better to be distracted by the mind numbing, soul sucking, time wasting threads than deal with my anxieties the second half of 2024 represented. Or so my subconscious told myself.

The first order of business for the new year- unfollow/unjoin (times 10)

It’s been 2 days. I can feel the detox already.

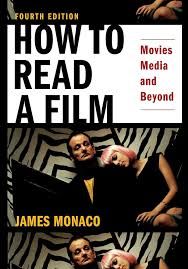

Why do I bring this up? Because I can also feel the natural instinct raising it’s ugly head when I come across a decent piece or quote or idea and immediately want to go and tandem post. I had such a moment today breaking open one of my Christmas presents- the book How To Read A Film: Movies, Media and Beyond (Fourth Edition).

I’m 10 pages in to tackling the 700 page beast and I’ve got two pages of notes reflecting on how the history of the word art mirrors the history of modernism and the enlightenment, shedding light on how it is we have come to see and know the world we observe and experience (these 700 pages are clearly going to take a while). Which of course connects directly to our ability to give langauge to the abstract and parse out how it is knowledge relates to our ability to interpret the abstract using symbols (art, at its core- imitating reality)

I’m hooked. I wish I could sit down and talk with someone about these 10 pages into the late night hours.

I can also tell you exactly what the response would be if I posted any of these observations and reflections for consideration in these groups. Then again, never mind, i won’t go there. That’s in the past. This is now. The second order of business- remembering that I have this space to get these thoughts out of my head and on to the page where, at the very least, I know they are somewhere safe and I can feel free to continue on.

So about this book:

It starts with a quote by Robert Frost

If poetry is what you can’t translate, then art is what you can’t define.

And yet what is an investment/interest in art (or the arts) but the attempt to do precisely that, always with the knowledge that such interpretations can only ever remain subjective, not objective.

Isn’t this how knowledge of the world, of reality works though? After all, if reality could be reduced to a handful of data points derived from the scientific process we wouldn’t need art. And yet art remains as critical for our modern world as it was for the ancients. It has simply become a present casualty of that modern development. The book talks about how the boundaries for what is seen as art has progressively expanded, while that expansion has simultaneously narrowed and diluted it in other respects. Much in the same way modern society has narrowed and diluted its relationship to culture here in the West.

An important observation from the book- for the ancients the arts could be broken down into 7 categories (History, Poetry, Comedy, Tragedy, Music, Dance, and Astronomy). These categories were unified by a “common motivation: they were tools, useful to describe the universe and our place in it… the performing arts celebrated the rituals (of human existence), history recorded the story of the race, astronomy searched the heavens.”

So what changed precisely? The arts got coopted by the enlightenment. The arts were reconstituted as a purely “practical” means of making sense of the world, following this movement in the West towards reducing knowledge and truth to the scientific process. Art becomes the social sciences, the modern sciences, historical criticisms, mathematics, “structural” sciences.

The only two that remained unchanged- music and astronomy. More on this in a bit.

Art becomes so diluted that it gets applied to nearly any practicality- hence the moniker “artistry” or making. What ultimately emerges- a separation between art/artist as one who studies and gains knowledge of the world and the scientific disciplines that reduce this world into utility and function. Along with this comes a differentiation within the category of the arts as well, between the one who creates (artist) and the one who makes (artisan). The artist held the lower standing, the sciences and the artisan held the higher standing. And even within the arts this hierarchy took hold (the visual makers versus the abstract creators)

As the book states,

The arts were no longer simply approaches to a comprehension of the world; they were now ends in themsleves.”

And even then, the entire existence of avante garde, an idea that sees art as necessarily progressive in line with the enlightenments allegiance to scientific progress as the sole proprietor of knowledge and truth, ensured that this separation would persist- art had to become something, it had to conform to a set of visual and structured rules in order to coexist in this new world of practicalities, and eventually this new world of politics (modern art can almost be reclassified as political discourse).

Remember when I said that music and astronomy were the only two that remained unchanged? Here’s what’s interesting about that. The book notes how both astronomy and music occupy the same prersistant grasp on the abstract and the same stubborn refusal to let go no matter how much “progress” we find. They are artistic elements that cannot be tamed or reduced by nature of being fluid and requiring movement, and thus they anchor, on both ends, this notion of the arts in the experience of the abstract. They require artistic interpretation the same way it did in the ancient world. Pick up an astronomy book and you can see this to be true. They often read like religious texts. Try to grasp and understand what music is and how and why we experience it the way we do as a transcendent, religious type of encounter, and you see this to be true. As the book quotes, citing Walter Pater,

All art aspires to the condition of music

The condition of music- the pure abstract being formed into knowledge.

As I stated above, historically art imitates life. In the modern world, life increasingly imitates art. What’s the difference? One is seeking to understand the world by way of applying symbol (interpretation) to sign (observation). The other conforms our symbols to the sign, effectively collapsing sign and symbol together into a singular way of knowing and seeing the world (science, or form, function and utility). It’s the difference between seeking to understand the image of the world and believing we can make the world in our own image. After all, what is science but the accomplishments of humanity.

And yet, what does it mean to encounter a film. To be moved by a song or a score. To be transformed by a story. To reflective on and ponder the grand mysteries of the universe. It means the barrier between art, artist and participant has been transcended. It awakens us to knowledge and truth that we did not obtain ourselves. It seeks to make sense of that which we cannot make sense of ourselves.

It reminds us that this world is not reducible to simple matters of form and function. Even to say that it is would require art- an act of interpretation. These things emerge from that which precedes it, from its source, thus it cannot be understood without that necessary foundation to interpret its meaning, its value and force. And it is that foundation that art seeks to discover and to reveal.

Art, therefore, doesn’t just imitate life, it imitates the transcendent. It makes the invisible visible. Hence one of the great lies of the modern age being this- that any amount of scientific disciplines and discoveries can erase the necessary need for art. Science is but one way of knowing. The ancientss understood this. We have come to see ourselves as better and smarter and wiser and more knowledgeable than those primitive folk way back then. Art can remind us that we are, in fact, not. If anything, we’ve simply taught ourselves to see and think more narrowly about knowledge and truth.