Google the question “can we trust our memories”, and the answer that comes up is an emphatic no. Despite memory being the only tool we have to recollect the past, it is notoriously untrustworthy in the way it reconstructs facts and conceals the truth.

My earliest memories reach back somewhere into the recesses of my childhood. I have vague imprints in my mind of old houses and neighborhoods, old faces and experiences from around 4 years of age. Beyond the persistent and chronic nightmares of my preschool self though, which linger in my mind with a striking degree of clarity, my earliest and most vivid memories come from grade 1 and 2. I can remember one particular morning riding to school in the backseat of our old station wagon. My younger brother had just started attending school, and on this particular day was excited to bring his hula hoop to play with during recess. Only, as we both exited the vehicle he promptly realized that he had left it in the car. The devastation on his face was immediate and palpable, and my instinctual reaction was to take off down the street after the car. To no avail of course. Perhaps most acute is the heartache I carried with me for the rest of that day. As his older brother I had failed to solve the problem, and it is a moment that remains imprinted in my memory to this day.

In her book Remember: The Science of Memory and the Art of Forgetting, author Lisa Genova notes that

“most of us will forget the majority of what we experience today by tomorrow. Added up, this means we actually don’t remember most of our lives.” (P3)

Which of course begs a further question in light of my noted experience above; why do we remember certain parts of our life and forget others?

At least one thing seems obvious; experiences that hold the most emotional weight seem to stick around the longest. Genova does a great job in her book of answering this question with observations and insights from science, ultimately rooting the ebb and flow of this remembering/forgetting exercise in the necessary narrative of our lives. She suggests that

“memory is the sum of what we remember and what we forget, and there is an art and science to both.”(p9)

The science then is the observation of brain function while the art is the act of rooting this function in a sense of identity and story. Both of these things together can help us locate the why of our inherent human need to both forget and to remember, while also helping us to understand the how. Genova writes,

“The significant facts and moments of your life strung together create your life’s narrative and identity. Memory allows you to have a sense of who you are and who you’ve been.” (P2)

And yet this still doesn’t solve the essential conundrum of personhood and identity when it comes to the unreliability of our memories. Echoing this problem, Genova writes,

“Much of what we do remember is incomplete and inaccurate… our memories for what happened are particularly vulnerable to omissions and unintentional editing.” (P3).

So if memory is necessary to who we are, how then do we reconcile this with the idea that who we are seems to be reflective of a false version of reality? Genova asks the question this way:

“So where does that leave us with respect to our relationship with memory? How should we hold it? Do we revere our memory as an omnipotent monarch, or do we throw rotten tomatoes at it, denigrating it (and by extension, ourselves) for its inconvenient shortcomings and foolish mistakes?” (P228)

What seems clear is that this problem is made more complex when we consider our relationship to both positive and negative memory. As scholar Robert Vosloo writes in his article Time in our Time: On Theology And Future-Oriented Memory,

“Narrative memory is never innocent. It is an ongoing conflict of interpretations: a battlefield of competing meanings.”

Vosloo points out that remembering is, historically speaking, a Judeo-Christian idea. With the Greek gods, and in the long standing myths that precede them, remembering and forgetting are in fact expressions of gods at war, relating specifically to how we engage what we perceive to be positive and negative experiences in contest. In this light, positive memories do not so much hold a true correlation to reality as much as they exist to control the negative. This is how we live forward through forgetfulness. If for Genova we forget so that our brains can process, forgetting reveals something crucial about how we process and what we process. Memory seems deeply tied to meaning making, and meaning making wrestles with the negative realities of our existence.

In fact, Vosloo also argues that acts of forgetting have come to define the modern landscape as a sort of virtue finding that guards against the past and helps feed progress. Thus,

“the apparent power of this thought, namely that memory of the past impedes our wellbeing, points in the direction of the necessity to ask about the rightful place of memory in our moral and theological discourse, particularly when one argues that the past is not dead, but is present as triumph and as trauma, as gift and as ghost.”

In other words, to speak of memory in a theological sense means to remember differently than our nature seems to allow. Memory becomes a necessary spiritual discipline.

Elie Weisel in his annotated Nobel prize speech, offers his own observation on the subject of memory, suggesting that,

“Remembering is a noble and necessary act. The call of memory, the call to memory, reaches us from the very dawn of history… And yet it is surely human to forget, even to want to forget. The Ancients saw it as a divine gift. Indeed if memory helps us to survive, forgetting allows us to go on living. How could we go on with our daily lives if we remained constantly aware of the dangers and ghosts surrounding us…”

He then affords the conversation this subsequent question:

“How (then) are we to reconcile our supreme duty towards memory with the need to forget that is (or seems) essential to life?”

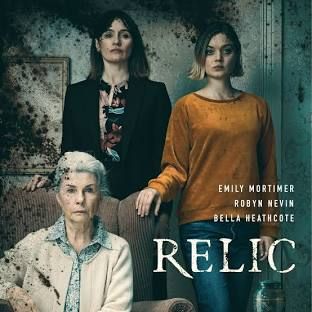

Natalie Erika James’ film Relic is a film I have long championed as an underseen gem, and i think it has a lot to add this particular conversation about memory. The reason this film is important to me is because of the way it tackles the theme of memory from the vantage point of its decline. It tells the story of two daughters moving back home to care for their ailing mother who is sick with alziemers. As they return home we see the daughters engaging in an act of remembering, which contrasts with the mothers struggle with forgetting. This becomes a powerful juxtaposition that leads them towards a crisis of identity. In a very real sense their act of remembering leads to a need to forget what is a painful reality, while the mothers act of forgetting leads to a desperate need to remember in light of her painful decline. In both cases this posits a discussion of identity; what does it look like to still be a person in the absence of memory.

It is here that this quote from psychologist Alexander Luria emerges, echoing the struggle while attempting to cast it in a fresh, redemptive light. He writes,

“People do not consist of memory alone. They have feelings, will, sensibility, moral being. It is here you may touch them and see profound change.”

In other words, people are located in the act of living in the present, not in the echoes of the past. A present that is nonetheless shaped by the past. All memory serves the present. Thus is why our brains continually rewrite our memories to serve the narrative now. It’s far less important for those memories to be accurate recollections as it is for them to be necessary applications

As Weisel suggests,

“If dreams reflect the past, hope summons the future. Does this mean that our future can be built on a rejection of the past? Surely such a choice is not necessary. The two are not incompatible. The opposite of the past is not the future but the absence of future; the opposite of the future is not the past but the absence of past. The loss of one is equivalent to the sacrifice of the other.”

There is far more to flesh out here in terms of how these different voices see a way forward through the challenges that memory presents, especially when it comes to our indebtedness to it as persons, as ones seemingly needing this notion of a true and real identity.. But I wonder if Weisel ‘s theological wonderings about the meaning of memory and Genova’s detailing of the science of memory is less about the accuracy of facts we remember and far more about our ability to say that something simply is. We experience something. We come to know something. Therefore It means something when it comes to declaring who we are now in light of the past. And if there is a place to begin in rooting this in some sense of a truthful reality, in beginning to learn what it means to remember differently, or to remember rightly, perhaps it begins with an even greater concept and realization- the idea that we remember together. This is an idea I will explore further in part 2 of this post.