Anatole: Does your Bible oppose slavery?

Liesel: I oppose slavery.

Wes Anderson’s films are no stranger to exploring philosophical and existential questions. Beyond the dark humor, the quirkiness and the singularity of his unique style, lies much bigger questions about life, the world, and at times God.

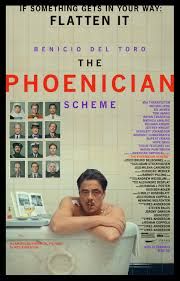

His latest film, The Phoenician Scheme, follows the journey of Anatole Korda, someone we meet in the throes of repeated assassination attemps on his life due to targeted business practices which place capitalist pursuits over human welfare. Here we are thrust into the mind of a man who’s near death experiences are leading him to evaluate his priorities. Priority number one is securing a successor to his business and estate, and although he has numerous sons, it is his estranged daughter, Liesel, whom he has in his sights. An unlikely candidate given she is currently immersed in her pursuit of becomming a nun.

It is this clash of worldviews, including the opposing moral centers, that becomes the framework for this very human journey. The father is as worldly as they come as a self declared atheist, while the daughter is in the process of denying these worldly pleasures for the sake of her devotion to God. Here the story arc bends towards these two estranged persons finding a way to bridge this divide and forge a connection in ways that can make sense of their competing values and convictions.

What’s striking then about how Anderson plays these two interconnecting stories into a similar search for meaning and purpose is how he finds these two competing visions being brought into conversation. At the heart of this journey is uncovering the mystery of Liesel’s mother’s murder, a fact that lies at the root of their estrangement. Over the course of the movie Liesel becomes more and more worldy, while Anatole moves closer and closer to a kind of spiritual awakening. On the part of Anatole we have these sequences which reflect his near death experiences, which continually contront him with the reality of his own choices. Liesel on the other hand is found to be wrestling with her untold doubts, something she is buried under the convenience of assumed duty. Eventually these paths intersect, finding a kind of redemptive picture in their mutual acts of giving up control in their own way. Discovering what truly matters within their divergent searches for meaning.

There is a point in the film where Liesel is talking to mother superior, insisting that she is ready to take her vows. Mother Superior denies her this appointment, but includes this caveat- this need not be a sign of weakness or failure. She finds in Liesel tendencies that seem bent towards being in the world, not removing herself from it. There, mother superior insists, she can find God.

On the part of Anatole, a world in which he does not expect to find God is precisely where he encounters this spiritual awakening. This leads him to abandon his allegiance to the worldly pleasures. He sells that which he has been enslaved to and reinvents himself in a more modesst living expressed not by gain, but by virtue.

What lies at the heart of both of their journies is a reclamation of what it means to be in this world as people shaped by something other than the world’s base material function. Here the film quietly breathes in notes of transcendence which do not fit neatly into any of their constructed journey’s, let alone the reductionist view of Micheal Cera’s character, the “scientist,” someone who’s own sense of needed control seeks to find meaning and value in a rational assessment of nature. All three of them reflect the need for a foundation, a foundation that is deeply dependent on the narratives that are shaping their lives and their participation in the world. A narrative that needs to attend for this transcendence in order for their lives to make sense.

Which is to say, narrative matters precisely because we are participants in this world. We cannot escape this. This is why the questions they each are asking from their individual vantage points matter. At one point Liesel makes a powerful concession. When I pray, she states, I never actually hear God. I pretend to. And then I act based on what I think God would say, and usually that’s in alignment with what I need. A reminder that if God exists, we would expect to find God in the lives of people seeking to live in the world in ways that run counter to the world. This is how she finds God in the world. This is also how Anatole, living in his own godless universe, learns how to pray. In both cases this brings us to the point of seeking- having both a passion for the truth and a willingness for the truth to transform. A transformation that represents itself in the acts of living, and indeed praying, truthfully.