“When someone dies or disappears, we can tell stories about only what might have been the case or what might have happened next. And perhaps it is simply a question of control, but it is easier to imagine the very worst than to allow a space in which several things might be true at once.” (The Homemade God, Rachel Joyce)

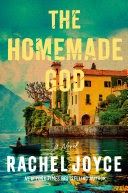

Joyce’s recently released novel follows a disjointed and entirely dysfunctional family (aren’t we all) on a journey to deal with the sudden passing of their father. At the heart of this story lies two great mysteries- what happened to their father’s allusive and non-existent final painting, a project that was intended to define his legacy, and who is this much younger woman he recently married. As this cast of siblings comes together, these two essential mysteries begin to pull at the fabric of their collective and seperate pasts in the way the loss of a parental figure often does. As the story progresses, it becomes more and more clear that the grater mystery is in fact not this enigmatic figure that was their father, but whether they themselves can be reconciled both to him and one another against the push and pull of their individual stories.

It’s a book that is largely about the shifting nature of our perspectives, especially where these differing vantage points are brought into conversation. Who their father was to each of them matters to who he was as a singular entity to the whole. In many ways these are competing stories, competing stories that, as the above quote suggests, wrestle with how it is we imagine our perspective within the framework of past hopes and regrets. Is my perspective true? In one sense yes. This is the story we bring to the table, a fact that demonstrates the simple observation that all of us then are beholden in some way, shape or form to the perception and memory of others. This is something we cannot ultimatley control. It does however underscore the immense responsibility we hold in having the power to define and shape the story of others.

Here in lies an important facet of the novel, contained within the above quote. It is always easier to imagine the worst, especially where relationships are stained, estranged or distanced. This is precisely where imagination becomes our most powerful tool. Not because we are imagining something that isn’t true, but because our imaginations open us up to greater possibilities, challenging the limiting nature of our individual perspectives. It hands us an ultimate and necessary irony- we shape who others are, but it is the collective that shapes how we are able to see who others are. In the language of Joyce’s novel, this same notion applies to the creative or participatory acts we put out into the world as expressions of our selves and our limiting perspectives.

As I’ve been thinking about this idea over the last couple of days, I’ve actually found myself thinking more about the people in my life who are alive rather than the ones who are no longer around. I mean yes, in many ways this process is shaped by those legacies that get left behind. Legacies that are less defined by what we accomplish and more by the simple fact of our existence. But the only way to have a legacy is for that thing to exist in relationship to the world in the first place. In many ways this feels like a freeing thought. A liberating thought. I am free to embrace this experience in the moment for what it is while also knowing that this story is not bound to the moment. To feel bound, or to bind something to a given moment is where we are failing to engage that imagination.

The power of this thought, for me, is that this applies not to how I shape my life necessarily, but to the responsibility I have for shaping the stories of others. To learn to live this way is to learn how to see beyond myself, and to see beyond myself is to be free to see myself as a necessary part of this collective picture. This doesn’t dilute and devalue how it is we live in the experience of a given moment, as though what we do doesn’t matter or have an impact. It actually liberates those moments to be wrestled with and therofore eventually transformed. It makes space for several things to be true at once. Which of course flows from that necessary foundation- that which we can say is inherently true about this reality that we all share.

This probably needs its own seperate thread, but I can’t help but think about the ways I find this best expressed in the Judeo-Christian narrative. The idea of the homemade god is always seen and understood to be an image, a shadow, a representation. Where this is defined as worship of something inherently false (idolatry), leads to stories that are bound to a given moment. In the biblical narrative this is the language of exile- the dysfunctional and estranged family. Where this is defined as worship of something inherently true, this leads to stories that are liberated by the language of fulfillment. This is the language of new creation. The language of Jesus. It is this christological lens that allows the writers to re-imagine the story of exile-new creation in the sense of several things being true at once. In the language of Paul, evoking the already-not yet nature of telling our stories in the light of the risen Christ.

Now, this is where my imagination not only participates in the stories of those still here and shapes the stories of those who have passed, but entrusts these stories to the reality of the resurrection. The ultimate vantage point.