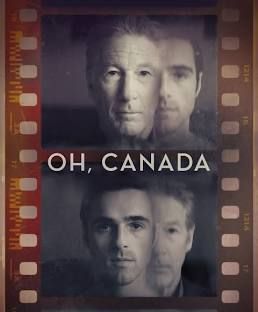

Paul Schrader’s latest film Oh Canada tells the story of a dying artist (a film Director) with a considerate legacy looking back on his life in an attempt to distguish which parts or versions of that legacy, if any, reflect the actual truth of who he is. Behind this film is Schrader’s own legacy, giving a fascinating layer to the on-screen story as he seemingly uses it to flesh out the uncertainties and perhaps disillusionment with his own legacy and career.

If I gleaned something from subsequent interviews with him on press tour for this film earlier this year, it would be that his own wrestling relates directly to how he sees the way in which his art appears to reflect a disconnect with his actual lived life. Almost as though these two things are at once inseperable but also seem to exist forever in tension, and almost seemingly irreconcilable on the surface. Especially when filtered through that illusive thing that is our memory.

Here the presence he holds in the consciousness of the aging generation is set in conversation with the new and emergent one, a fact that, when turned inwards, seems to push such wrestling into the realm of the exisential crisis. And yet what results is something hopeful. A semblance of coherency within the disonnance that suggests somehow and in someway these versions of himself matter. Perhaps, even, they matter precisely because, as legacy and life would suggest, we are never the true authors.

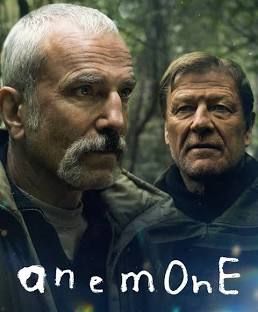

In Daniel Day Lewis’ latest character study, Anemone, which is directed by his son Ronan Day-Lewis in one of the most profound and impressive debuts in recent memory, tells the story of two aging and estranged brothers who’s sudden reconnecting becomes a means of exploring those larger connections which bind a life to generational patterns and cycles of the past. Here the film, incoporating a highly visual approach to the storytelling, asks us to examine the shape of our own lives within the complex interplay between our choices and our need for such choices to be shaped into narrative trajectories. This, it seems, is what affords us the measure of a life, even if it tells the story of failure and regret.

Part of what Anemone is, in my subective interpretation of course, seeking after is this suggestion that we are all a product of these lived spaces. And these lived spaces exist in relationship to that which it desperately seeks and desires beyond ourselves. Here the visual nature of the film alludes to the transcendent nature of this journey, rooting legacy not in accomplishments or successes, but in our awareness of the tension.

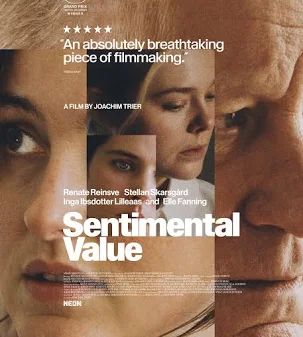

In Joachim Trier’s latest, Sentimental Value, it is the lingering presence of a single house that functions as a window into the story of the estranged family whom occupies it. Inside this home are the captive memories of muted joys, held and misunderstood secrets, and buried struggles which continue to echo far beyond its walls. Outside of this are the threads that, when pulled on and followed, lead one back to these shared and formative spaces which inform how it is that we are occupying the present, often in search of what prompted one to pull on that thread to begin with.

An aged filmmaker also occupies the heart of the story in Sentimental Value, in this case it is the father, who’s potential final film comes with a pointed and intentional request for one of his duaghters to play the lead. On the surface the film’s mystery revolves around the question of why, a question that brings us through all of the interconnecting characters/family members that surround them. On a broader level, this mystery plays out into the thematic nature of the film within a film motif. The question regarding who is the one speaking in the film bleeds into the subsequent question of to whom is the film speaking to. It is only through answering these questions that we can begin to unpack the why of this particular story. Here it becomes clear: the narration matters.

One of the most dynamic and powerful aspects of Sentimental Value is the way the process of these characters seeking answers to these questions about the film within the film ultimately becomes part of our own process watching Sentimental Value. Even more so as the film seeks truth beyond the confines of the screen in drawing out the portrait of a life. The particular shape of these individuals quietly gives way to something more universal, and it is when we find oursleves in that story that the full weight of it comes crashing down all at once. Where it ultimatley leads us to is that uncomfortable and unsettling and often uncertain question- who is telling our story and what’s it about. That is the real question that legacy or memory seeks an answer.

All three films have left their mark on me over the course of 2025. I loved Schraders honest grappling with such questions. There is something comforting, even hopeful, about the idea that all possible answers are necessarily complicated and even, by their nature, obscured.

There was something extremely affecting about the ways in which Daniel Day Lewis’ character in Anemone finds in our stories that necessary need for reconciliation. To be reconciled to our stories is to be reconciled to one another, to this world, and to God.

In Sentimental Value, it was the daughter whom I connected to most deeply, especially where I was reminded that so often these questions leave us without the means to communicate what it is precisely that we seek or feel or experience. Where our stories need words but words do not suffice or aren’t available. Where we are not capable. Sentimental Value reminded me of why art matters to this end. It gives sense to those spaces where we cannot act on our own. It becomes a way of telling our stories, precisely because art exists external to us- it can tell our stories because it exists in relationship to us. Even more, it can bridge those gaps where reconciliation is needed. It can speak on our behalf by saying what we can’t.

Here there was something about the buried darkness the daughter carries, having occupied similar spaces myself in the past regarding the depth of depression and the deep rooted tendency to retreat and cut onesself off from all the chaos, and even contemplate conceptions of imagined endings. And how into all that story, art, can be a powerful healer. Stories that are at once not our own, but that become our own. Stories that allow us the ability to see beyond ourselves and towards the great Other. The Divi