Bi Gan’s latest creative venture once again finds the visionary director playing with the subject of perspective, seeing through the lens of this liminal space between dream or illusion and reality. If Long Day’s Journey Into Night reflected on how these transparent spaces translate to cinematic storytelliing and its relationship to form, this film takes that idea and blows it wide open. I wrote in my review for Long Day’s Journey that the film, in all its abstractness, is woven around this clear sense of a gradual and persistant movement, one that is captured in this progression through the uncertain spaces in time where things are never quite right but where there is hope of finding something complete. Something real. Something transformed. And more than simply telling a story, it invites the viewer in as a subject to be part of it.

Those same themes and ideas and processes and approaches are applied here, this time given an apocalytpic proportion. Where it becomes about even one of those ideas, it similtaneously finds a way to be about all of those ideas at the same time.

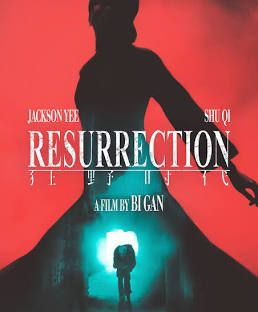

In Resurrection the journey is framed by the films structure, told as it is in six parts, each revolving around a different sense (beginning with vision and ending with mind, moving through sound, taste, smell and touch). Each part is set in a particular section of Chinese film history, beginning with the silent film era and moving through to modern expressionism. Here it is as much the story of cinema, seen through the lens of the Chinese cultural imprint, as it is the story of this enigmatic figure whom dies and rises as someone new in each period (all played by the same person within the film). In fact, one of the most signficant factors of Gan’s film is the way cinema becomes a character in and of itself. Resurrection is, in a very real way, telling the story of the dying and rising form through the ages, leaving us with a very real existential question in the wake of its final composition- what do we do when cinema dies? What does cinema itself do? Will it always be resurrected?

Could there be a more timely question for the present state of the American industry, something that many of us are feeling north of the border as well where we struggle to regain a focus on our own regulations and vision for the arts and this specific form? It feels like this could be necessary viewing for anyone looking to recover some sense of what that is in a world where the artform is gradually being reduced to a war of content and politics.

Gan leaves an unsettled and largly haunting sense of potential paths or futures lingering in the backdrop of the films historical narrative, but this isn’t devoid of hope. This isn’t hyperbolic doom scrolling through the inevitable collapse of all things. It’s also not being told through an american lens, thus it is bringing its own set of questions to the table regarding its examination of this universal language. In some sense it wants the liminal space it is creating, between what we hope for and what is in a world that is hard and where suffering is ever present and where death appears to have a final word on beauty, to bleed out into the functional questions of our own lives. If we are trying to locate where this character called cinema is in the course of this film, to make sense of its arc through the history the film is telling, we are, in a very real sense, looking to locate ourselves as well. As silent film in all of its potential starts to disintegrate in front of our eyes, giving way to the technology that drives the form forward into a new era of film theory, where do we root ourselves? Where does the truth persist outside of this aimless thing we might call “progress?” What is this thing called cinema and what language does it speak? Is it still, as it was born into this world as, a visual form? Can we detach it from the embodiment that we as viewers give it in relationship to the “experience” of the artistic creation? Some of the most startling images here involve the disintegration of that embodied form. The erosion of that interconnectedness.

It’s a fundamental question regarding the nature of cinema, and given that the history of the modern world follows this history, it raises fundamental questions regarding the nature of modernism and film. Where the film really digs in is seeing both of these things as affectijng our understanding of the nature of our own humanity. All of these things get intertwined. The death of cinema is always the death of ourselves. The question thus posed is one that can only get told through the act of mythtelling. Or it’s more accurate phrasing, Truth-Telling.

What Truth is underlying modernism? An age where the line between technology and experience is not only getting blurred, but reconstituted as a disembodied form- where we become products of progress. Wherein do we locate the form, the art, that becomes the question when it comes to telling a different narrative. And if Gan is emblemetic of the forms power to transform, regardless of the grip modernism holds, this is a celebration of that marriage between form and experience, the very thing that gives us the capacity to know anything at all. And one of the things that historical memory can awaken, in this case through the history of cinema, is that the way forward through such history is always through the necessary embodiment that connects form and experience to place. That’s the real magic trick here, something that sneaks its way through the overarching narrative and hits so powerfully in that final sequence- that while we are watching the story of cinema unfold, we are in fact watching our own story unfold. It’s one of the most startling meta-elements I’ve seen captured in a long time, where we see cinema looking at the world looking at the cinema has created on screen, and suddenly we realize that this character named cinema is interpreting us, sitting there watching this film. That’s the real power of the films lingering questions.