“All stories have a meanwhile- an important thing that’s happening while the rest of the story moves along.” (How To Read a Book, Monica Wood)

“But the rewards of a journey aren’t always immediate and aren’t always manifest. The point is, should we count milestones or miles? And the truth is I learned a lot from my time on the river- learned a lot, that is, about myself.” (Boogie Up The River, Mark Wallington)

The meanwhile of my story, in the plot turn that is my year in 2025, can only be found by looking backwards. Hence why I like to spend time each year engaging this retrospective process, in this case looking back on my reading year in order to try and parse out ideas, narratives, learnings, and themes that have emerged over the course of that journey.

Which also happens to be the reason why I always begin the new year with the next book in Toshikazu Kawaguchi’s Before the Coffee Gets Cold series (sadly I’ll be starting the last and final one this upcoming year, having read Before We Say Goodbye in January, 2025). This series reflects on the ongoing story of this cast of characters constantly engaged in looking back by way of travelling in time (or helping others through this process). As readers will know, these travellers cannot change the past and cannot leave the chair in this particular coffee shop (thus it can only travel back to a circumstance that happened in this space), thus the main question facing their choice of moment to return to is always about what they need to reconile or understand rather than what they can change.

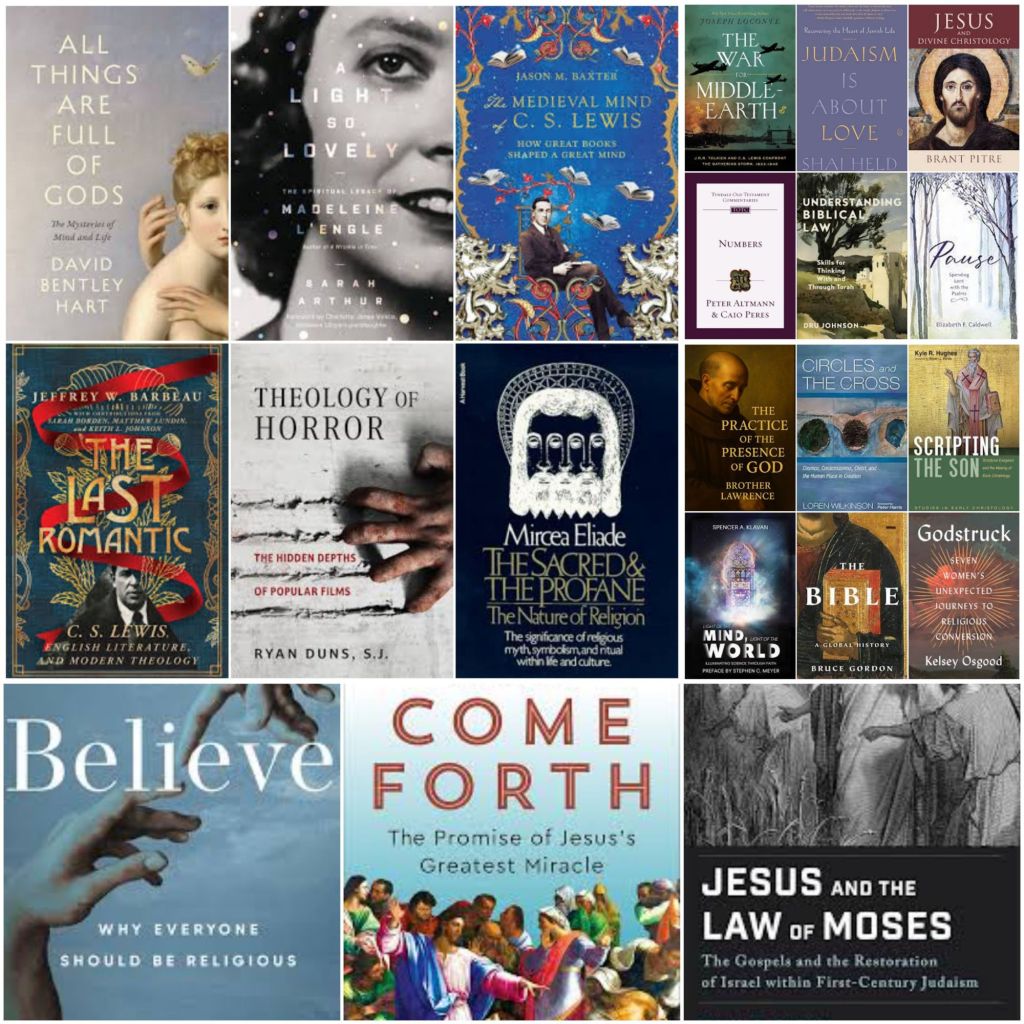

Beyond continuing this tradition, I started the year pulling random books off the remaining weeks of my month of kindle unlimited (activated to obtain some holiday reads) that all had to do with deconstructing Christianity’s allegiance to penal substitution. Not a new topic for me, and I’m not sure where these particular titles came from to be honest (its not like my algorithm was seeking them out), but where my year ended was in a far more intentional and oddly interconnected place, leaning into a handful of recently released books discussing issues revoloving around our understanding of the Jewish Law, especially in relationship to the Gospel and to the way we build our theologies (Jesus and the Law of Moses: The Gospels and the Restoration of Israel Within First-Century Judaism by Paul Sloan, Understanding Biblical Law: Skills for Thinking With and Through Torah by Dru Johnson, Paul and the Resurrection of Israel: Jews, Former Gentiles, Israelities, by Jason Staples).

As Kate Riley fleshes out in her intriguing book Ruth, so often the way into any inneral or internal critique is our ability to critique the critique, which she applies to the story of her main character navigating the thorny ground of religious community. Which simply means, a proper critique must always belongs to that larger conversation in which these different streams can grow and develop. In this case, Sloan, Johnson and Staples are all occupying space within a stream of theological concern that stems back to the original voices of the new perspective. What stood out to me in 2025 was simply the excitment of seeing the fruits of that conversation really beginning to taking shape in what is now a robust and dynamic debate.

If critiquing the common allegiance to penal substition is often a place to start in pushing back on certain western theological tendencies, the natural outflow of this conversation is the recontextualizing of the images and conceptions of Temple, Law and sacrifice within their ANE and second temple context, which is arguably the much harder work of reconstruction. Over the course of this year, these books and others have accentuated the fact that so much bad theology comes from a failure to understand these things (and I would throw in the terms exile and exodus) in their world. And this has massive implications for many areas of our thinking, our beliefs and indeed our living, from how we understand and apply a term like salvation or justice to how we understand larger conceptual frameworks like hope and transformation.

At its heart, the law and the temple, exile, exodus, and the sacrificial rites are narrative constructions that tell a story that, for those of us who hold it to represent a true representation of a God revealed in history, has the power and authority to inform our own. Who I see myself to be, who I see others to be, what I understand the world to be, is intimately tied to who I see God to be, particularly because this becomes the lens through which I understand and thus relate to the world I observe and experience. The story we bind ourselves to matters immensly to the story we tell through our participation in the world. And one of the beautiful things about entering into the story of Israel, which all three of the above books help us to do, is the way it opens up the patterns of life itself. Indeed, the way to understand a story is to understand the patterns contained within, and these patterns are so often attached to this constant movement between spaces and the engagment of cycles.

Perhaps the most ready dynamic of this discussion of ones partticipation in the world applies to my encountering ongoing discussions in the books I was reading about understanding and reconciling the relationship between our constructed world and the greater reality that this belongs to, often given the name “the natural world.” Barbara Brown Taylors An Altar in the World: A Geography of Faith expressley parallels our life in God and Spirit with our connection to the natural world, seeing it through the framework of the movement and within the cycles of its seasons as being accessed through a necessary retreat from the constructed world (society) into nature.

I have often expressed the fact that I am an odd one in this regard, as I am most at home where I find human participation (society and culture) existing in relationship to what we might call the wilderness. I have never been one to find solace in the wilderness, which of course is always an idea worth unpacking, but for this moment, if Taylor’s vision sees the wilderness as a somewhat antithetical space to the societies we inhabit, there were three books in particular that took a different angle. They were expressely about our ability to expand our understanding of nature to include the whole of human participation (Timeless Way of Building by Christopher W. Alexander, The Myths We Live By by Mary Midgley, and perhaps one of the most definitive works I read this year Circles, and the Cross: Cosmos, Consciousness, Christ and the Human Place in Creation by Loren Wilkinson). Each of these books imagines a marriage of wilderness and city as opposed to setting them over and against each other.

In all three books one of the central critiques is the way our modern tendency to replace the old myths with new ones (such as environmentalism and other natural philsophies), myth here being used in the proper sense of a story that anchors us in what is really true about this world and our existence, create this problem of narrowing our conception of nature in ways that cannot speak to the whole. What we need is a myth that can give meaning to both the idea of human particpation as co-creators (or subcreators) as well as to the larger reality of the wild world that this belongs to.

We need to explan our understanding of nature in ways that include the whole.

Unfortunately in a modern world that has sought to distance itself from religion, one of the outcomes is this grabbing at meanings of the word “natural” that distances itself from any inclination of metanarratives, especially concerning the percieved notion of the supernatural but also including the particular human experience. We either find ourselves then swimming in the waters of our necessary but largely irraitonal applications of humanistic concern, which act and function in this sense without approprriate defintion of logic, or we just end up diminishing the natural world altogether. Both Wilkinson and Midgely offer powerful arguments to this end, both seeking better stories through which to make sense of this world by seeing them as parts of the whole. And that begins with broadening our usage, our understanding and our defintion of the word “natural.”

To this end, I’m reminded of this quote from Susanna Clarke’s The Wood at Midwinter, a book I read in the early days of January this year.

“A church is a sort of wood. A wood is a sort of church.”

If this quote evokes this marriage between the wilderness and its human participants and its subcreations, which I think connects back to the prominnance of the parallel images of city and wilderness in the story of Isreal (something Peter Altmann helps bring to life in his commentary on Numbers which I finished this year, a commentary that was initially going to be titled “into the wilderness”), three travelogues also helps accentuate this idea.

Walking Home by Lynda L Wilson is a striking memoir that documents an aging individual whom finds herself randomly setting out to be first to walk this new trail connecting two parts of Southern Ontario. Not only is she not prone to camping or one to really revel in retreating to the wilderness in the traditional sense, but this trail that she embarks on brings her through the different communities that populate its way, actively bringing the city and the wilderness together. That is the memoirs true beauty. As she says at one point, part of what she discoveres is that she is indeed, as it is for all of us, the center of her world, but the truth she awakens to is that the world is everywhere.

Equally true for the journey Matt Savino takes and documents in a Land Without a Continent: A Road Trip Through Mexico and Central America, albeit a journey marked by a greater intent and purpose Here his journey takes him through the different wildernesses that become the pathways into different communities and homes and cultures. Or the enigmatic (and very Canadian) The Smiling Land: All Around the Circle in my Newfoundland and Labrador by Alan Doyle, which becomes a pilgrimage based on his desire to understand what a place, and this specific place, means to our (and his) stories. If ever there were a place where community and the great wilderness meet and coexist, it would be Newfoundland and Labrador, and the way he brings this to life is both meaningful and magical.

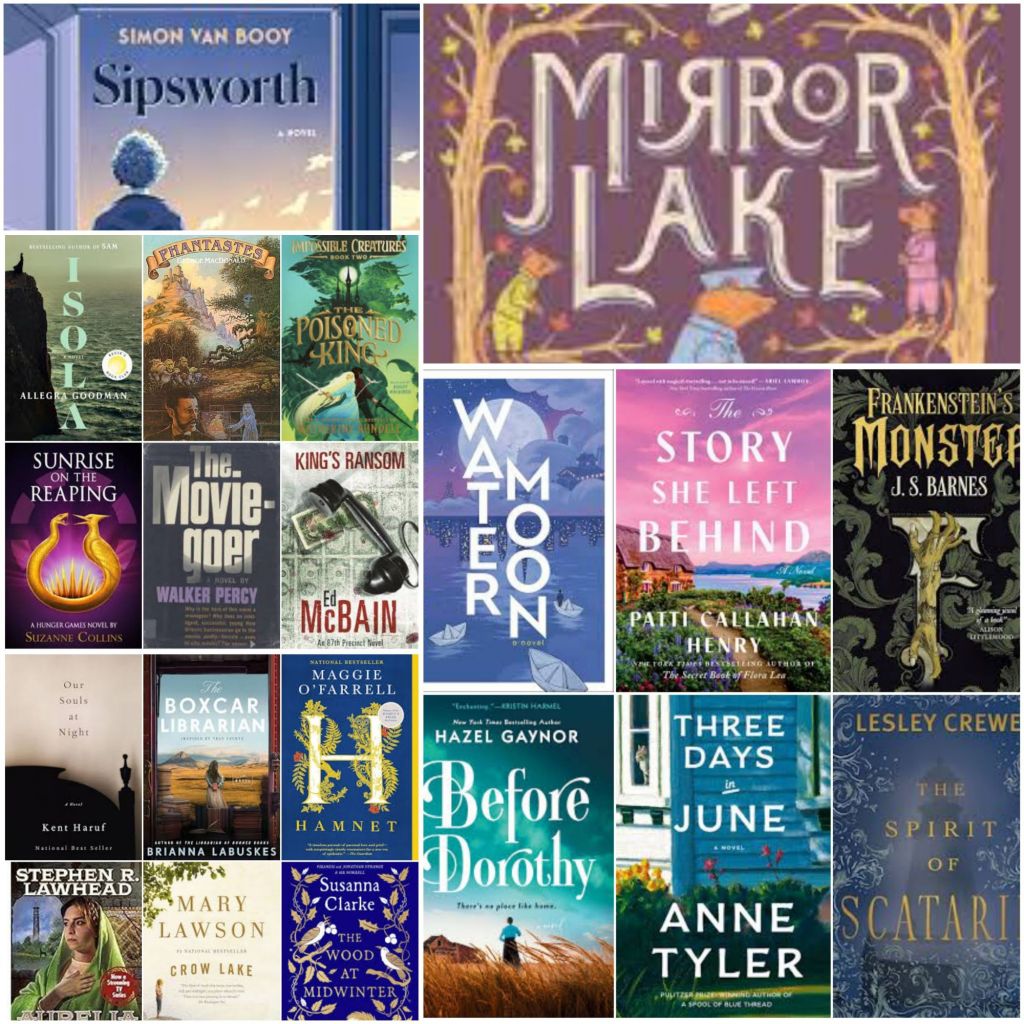

This theme, of finding a way to name the world that we are participating in, and indeed finding a way into the world by way of the wildernesss, I found opened up into these subsequent threads of how it is that we then occupy the spaces we encounter and inhabit as we go. As Walker Percy exposits in Signposts in a Strange Land, when we travel in life, be it in the figurative or practical sense, we engage myth-making and its outflow, truth telling. We tell our stories, we become aware of our stories. we become aware of the tensions that the stories reveal. And we do so in intimate relationship with the space and land we occupy, land and space that is perpetually changing with time. As Frances Mayes suggests in A Place in the World: Finding the Meaning of Home, a book I finally managed to pick up and finish this summer, we explore the meaning of home wherever we go. It’s as we go that opens up this sense of meaning. Or Mary Lawson in Crow Lake, a book set in northern Ontario which explores the tension between the human ambitions of the big city (the construction) and the identity that her main character finds rooted and contained within the isolated pages of this town in the northern Ontario wilderness she once called home. A town that she returns to with the realization that change applies as much to her as it does to this place. A story that digs into some of those bigger questions regarding why it is we sometimes want to escape and what it is we are escaping to, be it in a geographical sense or in an internal sense, and indeed what happens when we return to the once familiar spaces. For Lawson’s character and story, its largely about the expectations of what a place wants to be veruss what a place actually is, and how it is we occupy this space with our expectations in tow, moving towards notions of becoming.

Or, from the perspective of another Canadian author, Lesley Crewe’s book The Spirit of Scatarie, which explores this transplanting journey from life in the big city to life in this foreign and isolated island in Nova Scotia. It’s a stark reminder that the spaces we occupy and how we occupy them matter immensly to the stories they tell, especially in the way, as the book imagines, these stories are enchanted by . A sentiment made vivid in one of this years most celebrated titles, Wild Dark Shore by Charloote McConaghy, a book that is all about movement between spaces, between society and the wilderness.

On a broader level, I also found my reading year leading me through questions regarding the greater nature of this world which these spaces occupy. To tell our stories and to engage the story of any place or any life is to equally find ourselves seeking something outside of ourselves, calling us to remember the once enchanted world of our childhoods we have forgotten exists (Impossible Creatures/The Poinsoned King by Katherine Rundell, The Mythmakers: The Remarkable Fellowship of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien). A sentiment echoed in Meg Shaffer’s The Lost Story, declaring that “what is lost can be found.” A sentiment embodied in the journey of the main character in Patti Callahan Henry’s The Story She Left Behind, a narrative about a young mother having her world expanded and thus reenchanted as she seeks her own story in the midst of a her own figurative wilderness, a journey that finds her moving from the isoalted American midwest to the city of London, and then once again into the wilderness of the English countryside.

This gets a philosophical/theological bent in something like Mircea Eliade’s Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. Here she observes that “Even the most desacralized existence still preserves traces of a religious valorization of the world.” And indeed, as the travelogue Monsterland: A Journey Around the World’s Dark Imagination by Nicholas Jubber inadvertently shows, such a need to seek the image behind the reality is embedded in all of the worlds stories, something the above mentioned Mythmakers unpacks through its examination of the friendship between two of histories greatest thinkers on the nature of myth.

As Eliade suggests, the Sacred (defined as differentiation) and the profane (defined as homogenuity) gives way to this idea of the sacred sanctifying the profane. Mythic language begins with the cosmic at its center and then it moves out into the stories that shape our world, the people and places that occupy them. On this same note, I had something of a revelatory moment when I finished the quirky travelogue Go to Hell: A Traveler’s Guide to Earth’s Most Otherworldy Destinations by Erika Engelhaupt. The journey she takes in this book is geographical, but it is a journey through history., that being the history of the idea of hell as a conceptual metaphor and language. What I found so intriguing and profound about this was the simple observation that in the early going of telling this history she is firmy postioned in the old world and its myths. And it was rich and exciting and alive. It is when she gets to the later places that suddenly she is trying to shoehorn this idea of hell into a modern mythology and landscape which has stripped the language of any metaphorical power. This is a micocosm of this idea in play, to be sure, but it was the sheer emptiness of the modern lens that struck me in this regard. She might as well have abandoned the word altogether at this point, because it no longer had any meaning or power or ability to evoke anything beyond the empty descriptives of a place. It just felt the spaces she was now describing had no metahpor to appeal to. That it had lost its intrigue or meaning or depth in this transition is what struck me the most in this moment.

From the cosmic to the personal.

This might apply to something like an Empire, such as the question Alizah Holstein asks in her absorbing memoir My Roman History: What does a place do when it is no longer an Empire, when it finds itself being lost to the arrow of time yet somehow still existing within it at the same time. Such a question applies equally to the struggle of the individual, such as the feeling of being lost as an aging person in an aging world. (Sipsworth, Simon Van Booy), or a book like Water Moon (Samantha Sotto) and its emphasis on feeling like we don’t belong in the spaces we occupy. Which once again brought me back to that central concern of how the stories we tell in the present shape our lives in light of the past and the future, a question on the mind of the novel What You Are Looking For Is in the Library, Michiko Aoyama, where lost people are driven to seek some semblence of truth and coherency.

Part of the answer here of course comes down again to the question of our participation in this world, or how it is we participate in this world, forever traversing these paths between the wilderness and the city. Such as the call in Brother Lawrence’s The Practice of the Presence of God to engage in a life of prayer as acts of daily surrender, and the invitation towards participation in the liturgies of the daily life in Soul Feast: An Invitation to the Christian Spiritual Life by Marjorie J Thompson. And once again Barbara Brown Taylor’s call to make altars in the world as we go, marking the spaces as we encounter them so as to give this journey its shape. Adam Ross’ frustrating but fascainting and alluring romp in Playworld through a particular period of America’s history as an act of preserving memory. The preservation of customs and Traditions in Eliot Stein’s fantastic Custodians of Wonder: Ancient Customs and Traditions and the Last People Keeping Them Alive, a book that is bursting with that needed desire to constantly re-enchant the world as we go, where magic tends to be forgotten. The desire and need of Lewis to be reenchanted by the English Romantics (The Last Romantic by Jeffrey W. Barbeeau) on his own journey through the wilderness. Or the quiet power of my number one book of the year, Isola (Allegra Goodman), which follows our main character as she carves out and creates a liturgy of the everyday in a wilderness and circumstance that presses back on her in every corner of her experience of the world. Robert Macfarlane’s journey of finding the world reenchanted through its rivers (Is a River Alive), a sentiment shared by Mark Wallington’s Boogie Up the River, Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat, and Olivia Laing’s To the River: A Journey Beneath the Surface. The journey of seven women finding God in the wildernesss of their own worlds in unexpected ways (Godstruck: Seven Women’s Unexpected Journeys to Relgious Conversion).

And yet I was also struck on my own reading journey that for as much as this appears to define the shared quest of our existence, forever seeking the light in the dark, finding wonder in a world framed by cynicism, how it is we find this thing Pope Francis calls in his memoir “hope” (Hope: The Autobiography) in the wilderness requires one to constantly be willing to reconcile the world they are enountering with the specific narrative lens they are applying in any given moment. Again and again it seems to come back to the necessity of narrative or story as the driving foce for how it is we make sense of any of this thing we might call existence. Something James Monaco helps personify and embody in an artform in his monumental book How To Read a Film, an artform that is all about attending for the observer and giving defintions to the lens through which we filter the world we observe and experience. Spencer Klavan argues the same thing from the perspective of physics in Light of the Mind, Light of the World, one of the most definitive defeaters of materialism that I have encountered yet.

Here my reading journey kept coming back to that same question of how it is we understand our lens, both in what it is and how it is shaping our perspective. For example, in The Banquet of Souls: A Mirror to the Universe, Joshua Farris asks, what if we took seriously the existence of the soul- how does that lens shape everything else? His book becomes a philosphical exercise in teasing that question out. Or in Paul Shutz’s book A Theology of Flourishing, his thesis is built around the question, what if we made a theology of flourishing the lens through which we make sense of everything else. It reframes the world entirely. It leads us to ask different questions. Hopefully better ones,

Or in a really practical way, what if, as James Martin imagines in his book Come Forth: The Promise of Jesus’ Greatest Miracle, we understand the beloved disciple in John’s Gospel to be Lazarus (something he makes a really strong case for leaning on Ben Witherington’s work). How does that reshape the Gospel we are encountering, the words we are reading? The world behind the text? For me that became a powerful exercise in seeing how a simple lens can change ones entire perspective on the truth of a thing. What would it be for this story, these characters to be expressed through this lens.

Or, in one of the most defining books I read this year, what if, as Loren Wilkinson says in Circles and the Cross: Cosmos, Consciousness, Christ, and the Human Place in Creation, Christ is found at the center of all of our stories. This notion of Christ as our primary lens is not unfamiliar, including being represented by another wonderful scholarly work I read this year, Scripting the Son by Kyle Hughes. But here Wilkinson provides a unique and sweeping vantage point beyond the interests of reading and encountering the scriptures, something that brings in the whole of the cosmos and the whole of history. And for me, what made this more powerful was reading the monumental work, Jesus and Divine Christology by Brant Pitre alongside that, which for me makes an incredibly strong case for being a definitive defeater for the whole quesiton of whether Jesus saw Himself as the incarnate Christ shaping the middle of history or not. Pitre leaves little doubt for me that this is the strongest explanation for the evidence, that the reason we find this in the Gospels is because Jesus saw and understood and represented Himself to be precisely this. And if that is the case, then adopting this lens takes on far more than a theoretical exercise.

If Timothy Caulfield is correct, and I think he is, there is a caveat to all of this. His premise in The Certainty Illusion: What You Don’t Know and Why it Matters is a qualifying reminder that what upholds any lens is the necessary tension and paradox that accompanies any knowledge of this world. Here knowledge is not information but rather reflects our true awareness and understanding of the world we observe and experience. Just as the Kings Ransom (Ed McBain) imagines the moral tension that shapes and accompanies any social and societal construct, often over and against specific western appeals to this concept of certainty, so does any appeal to a given and applied worldview. In a specific Christian sense this gets unpacked in Suprised by Paradox by Jen Pollock as an essential rule of the life of faith and belief, but in a way that we find inherent in all things.

Or, what if the typical globalization of the western lens which gets applied to America at its cener gets applied to historical narrative stemming from India as its applied lens instead. This is what we find in The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World by William Dalrymple, a book that equally brings the tensions of its own narrative to the table by way of this transplanted lens. To put it succinctly- the imagined world in The Golden Road looks a whole lot different than the imagine in a book like Shadi Hamid’s The Case for American Power (one of the worst books I read this year).

We can equally step out of the particular stories of Empire and look at the larger reality of how the world itself works in The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle AGainst Fate by Robert D. Kaplan. A book that throws into question all of our narrowed assumptions and narratives regarding any occupation of our space as the center of world history.

For example, in The Great Divide by Christina Henriquez, and equally in The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal by David McCullough, we are brought straight into the geopolitical tensions that played a central role in the rise of the West. If the Western narrative of progress becomes our lens we cannot escape the fact that we are equally upholding a history laden with such stories of oppression and conquest and power and politics. This finds a particular Canadaian context in Tanya Talaga’s The Knowing, which is a writing of our history through an Indigenous lens. Or a local interest in North End Love Songs by Katherean Vermette, writing a story of my neighborhnood with all of its tension filled history.

Ths would be equally true on a more sweeping level for the book Ocean: A History of the Atlantic Before Columbus, John Haywood, a book that brings us into both the prehistorical landscape and the recent history shaping the modern world by way of these interconnectingt tesnsions between the old world and the new, divided by the worlds most important body of water (embodied as well in the more personaly and narrowed story of The Waters by Bonnie Jo Campbell, which imagines these two worlds its characters are inhabiting poetically divided by the waters).

Or the tensions contained within a reading of our global history through the lens of coffee (A Short History of Coffee by Gordon Kerr). Or, as Bruce Gordon wonderfully unpacks in The Bible: A Global History, even in the creation of the Bible. As he writes,

“What defines the Bibles worth is the tension that shapes it… For Christians there is no greater fear than getting the Bible wrong.”

Gordon goes on to describe the Bible as “a book without end,” a notion that contextualizes its presence into the source of the tension- the fact that our human participation in this greater reality that informs the world behind the text finds us on this path between the human constructions and the wilderness. This is the same tension that we find in the story of one of the great living filmmakers (and one of my personal heroes), Del Toro (Guillermo del Toro: The Iconic Filmmaker and his Work, Ian Nathan). Here Nathan unpacks his journey of being caught between the dogmatism of his grandmother’s catholicism and the cynicism of his nihlistic father, which becomes the tension that fuels his storytelling and his own seeking to reenchant a world that he sees “destorying magic everyday.” A sentiment echoed in the storied journey of the main characters in Amy Sparkes A House of Magic.

These tensions aren’t just contained to feelings and experiences. They are are also, as my reading journey would unpack, contained in the fabric of our evolutionary and cosmic history. For Jeff Hawkins, A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence, the tension is personified in the image of the new brain literally wrapping itself around the old brain, a definitive and emblematic sign that explains our movement from the old world to the new, arguing that what was once necessary to survival of our species in the old world (emotions) now becomes a detriment to a new brain world built on technological advancement and information. Hence why the brain evolved the way it did. In James Kimmel’s book The Science of Revenge: Understanding the World’s Deadliest Addiction and How to Overcome It, he unpacks the tension that exists in our social evolution, between the natural seedbed of revenge as a survival mechanism and our perceived efforts to locate a coherent understanding of an emergent world that acts against it. Or the social realitites of a modern world in which we experience exhorbitant amounts of new found and emergent forms of anxiety rooted in the new and emergent constructs of this new world (Chatter: The Voice in Our Head, Why It Matters and How To Harness It). These are the same questions being posed in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and this years sequel Frankenstein’s Monster (J.S. Barnes) writing a story that sets the old world questions of our nature against the modern emergence of this new technological shift.

This would be the same tenion I found in Iain McGilchrist’s book The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, where he reclaims the old mistaken idea of the left and right brain by recasting it and reframing it within the emerging science. Here this echoes strongly with the experience of Donna Frietas, whom descrbies herself as feeling like a left brain person caught in a right brin world in her book Wishful Thinking: How I Lost My Faith and Why I want to Find it. A sentiment that once again pushes towards this notion of reenchanting a world seemingly purged of its magic and her self defining as one who deals with a chronic and perpetual restlessness towards this end.

Which brings me back in my reading journey as one that finds me along the way of rediscovering a world that contains magic. “Surely there is such a sea somewhere,” George MacDonald writes in Phantasies. Something that echoes with the grassroots nature of the convictions anchoring narratives like The Boxcar Librarian, Brianna Labuskes and Three Days in June by Anne Tyler, both of which marry ones investment in this participatory sense of life lived in relationship to a broader reality with the specifics of their own contextualized concerns, one social and one personal.

Like the touchpoint of the 1960’s that John Hendrix describes in Mythmakers describing the hunger of a generation seeking to identify with story in a culture of consumption, something they found in translating Tolkien’s universal appeal to the power of myth to their own time and space. Or Paul Kingsnorth’s Against The Machine: On the Unmaking of Humanity, where he deconstructs the modern myths and the impact they have had on a world that both seeks and desires real and true meaning. These religious yearnings are something these tensions reveal all over the place in human, social and societal structures, beckonging us on what is ultimatlely a shared religious quest. There is the idea of the sacred discourse as a conversation between the knower and the known in the already mentioned Godstruck: Seven Women’s Unexpected Journeys to Religious Conversion, Kelsey Osgood. Or the question in First Ghosts: Most Ancient of Legacies by Irving Finkel, which is why do we seek anything at all. The reshaping of our understanding of the Medieval world (and indeed the reductionist world the Western narrative has handed us) in They Flew: A History of the Impossible by Carlos M.N. Eire. Or the question and claim in Ross Douthat’s Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious. One of the key things I took away from this is the differentiation between the idea of hostile agnosticism (which is a product of a culture of certainty) and a yearning or seeking form of agnosticism (which defines the essential need and desire of the shared human experience). The latter understands that it is possible for someone else to know truth, the former operates on the underlying assumptions that such truth can never be known.

Here I am also reminded about the difference between knowledge and information once again. We have altered every aspect of the world that life, however undefined it has become in the modern lens, has occupied for all of its emergence in time (thus is the claim in A Briief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived: The Stories of Our Genes, Adam Rutherford). Which leaves us with the tension of a world which now sees and assumes in a contrary fashion, and often in a contradictory fashion to what we observe and know to be true about life in this world. If this is the case, what we have then is a battle within the modern consciousness between the tendency to want to reduce the world to something that we seek to control or find in the oberved world something that accords with our experience of it, which is an exerience of something that illuminates that which is outside of our control. This is what we find in Maggie O’Farrell’s experiment in this marriage of facts and possiblities in Hamnet, finding a way into the trancendent nature of a formative historical narrative by way of this buried historical voice. Or in the need to constantly recast the the stories of yesterday into new and fresh context and questions. (Frankenstein’s Monster by J.S. Barnes, R.M. Bouknight’s Cratchit, Hazel Gaynor’s Before Dorothy).

All of which bridge that universal concern that informs the human experience as an existing tension between life and death, light and dark, with the changing nature of our contextualized realities. Something that Sarah Arthur unpacks in A Light So Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy of Madeleine L’Engle, a historical presence whom held an astute and unique awarness of this tension and the transcendent reality that permeates the whole (made alive as well in the meandering Bright Evening Star: Msytery of the Incarnation, Madeleine L’Engle, one of my advent reads this year). She is someone who found herself caught between some of the trappings of progressivism and the problematic conservatism she was constantly critiquing. Ultimatley resting on the power of story/myth as the only proper way through the tension. An idea that Ryan G Duns plays out in his book Theology of Horror: The Hidden Depths of Popular Films, one of the more powerful narrative arguments for the Christian lens as the true myth that can make sense of all the worlds stories I read this year. Here he frames the universal tension embodied within the genre of horror and finds the mystery we are drawn towards called the holy. If the problem is a world or creation burdened by the frag-event of Sin, an enslaving force that impacts the whole of creation, Duns is specifically concerned with capturing the idea of knowledge as revelation. The revealed truth that God promised and did and still is liberating creation from the Powers of Sin and Death (the active or meta-paradox of it all). Moving through the tension we are able to move from the seed of horror towards the seeded desire for the Creative other in the incarnation. This becomes the means of bringing forth newness and transformation. It’s worth mentioning another book I read this year which offers similar insights, Joseph Loconte’s The War for Middle-Earth: J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Confronts the Gathering Storm, 1933-1945. Here the horror is war, and the hope the power of the truth myth that makes sense of all the world’s stories.

Perhaps this can be embodied on a broader level as being a bridge between the questions we find in a book like Sean Carroll’s From Eternity to Here: The Quest for the Ultimate Theory of Time, and the specific concerns of a book like The Invention of Good and Evil: A World History of Morality by Hanno Sauer. If, as Sauer argues, morality is a construct, something that emerges from societial and social function (which itself is a construct), this informs the essential tension that then informs all of life. Which is simply the question, how is it that we find both that which emerges in time and a reality that is, logically speaking, eternal or infinite. Meaning, there can not be a time when reality wasn’t. And yet the entirety of the human experience rests on this notion of the arrow of time. This is the language we understand from the position of our finite nature- things come into existence and they cease to exist. In our attempts to justify the time inbetween we then appeal to conceptions that we see having inherent meaning. We give a name to that which we suppose all of life is responding to as a way of reconciling this finiite nature of reality with its eternal or infinite quality. Take this away and the finite has no anchor. It is that act of naming that allows us to participate in (or with) the tension. And how do we name? As Will Stor says in The Science of Storytelling, through narrative. The key question that moves all of this however is, what Truth do these narratives seek to unveil and reveal.

If Ethan Kross is right (Chatter The Voice in Our Head, Why it Matters and How To Harness it), and “we spend upswards of half our lives not living in the present,” then this seems to point us towards that key and central idea and observation: everything comes down to narrative. As Olivai Laing writes in To the River: A Journey Beneath the Surface, ; “The present never stops no matter how weary you get. It comes as a river does, and if you aren’t careful you’ll be swept off your feet.” We are born into a story, we are born as a plot point within that story, and we live in concert with that story. This is the image of the river. It becomes an interesting question then; is being swept off our feet a good thing or a negative thing? A liberating force or a danger? Life or Death? Finite or eternal?

Narrative always points us outside of ourselves, precisely so that we might make sense of ourselves in this world. And what do we find when we look outwards?

“Life, they were surrounded by life- death’s instant and glorious opposing truth.” (The Poisoned King, Katherine Rundell).

“Surely there is such a sea somewhere…But I could not remain where I was any longer, though the daylight was hateful to me, and the thought of the great, innocent, bold sunrise unendurable… What distressed me the most- more even than my own folly- was the perplexing question, how can beauty and ugliness dwell so near… But it is no use trying to account for things in Fairy Land, and one who travels there soon learns to forget the very idea of doing so, and takes everything as it comes, like a child, who, being in a chronic condition of wonder, is surprised at nothing.” (Phantasies, George MacDonald)

“I believe in two things- God and time. Both are infinite, both reign supreme. Both crush mankind.” (Guillermo del Toro)

“Does a scientifically minded person become a romantic because he is a leftover from his own science… There was this also: a secret sense of wonder about the enduring… The enduring is something that must be accounted for. One cannot simply shrug it off.” (The Moviegoer, Walker Percy)

“The beginning of faith is not a feeling for the mystery of living or a sense of awe, wonder and amazement. The root of religion is the question what to do with the feeling of the mystery of living, what to do with awe, wonder and amazement. Religion begins with a consciousness that something is asked of us.” (Circles and the Cross: Cosmos, Consciousness, Christ and the Human Place in Creation)

“We will recover our sense of wonder and our sense of the sacred only if we appreciate the universe beyond ourselves as a revelatory experience of that numouos presence when all things came into being. Indeed, the universe is the primary sacred reality. We become sacred by our participation in this more sublime dimension of the world about us. (Thomas Berry)

“This book is a journey into an idea that changes the world- the idea that a river is alive. (The river is) “the drive to “reach the ocean.” (Is A River Alive, Robert Macfarlane)

A world full of information, and humans observing and experiencing such a world as part of the universal seeking for something beyond themselves- true knowledge that awakens us to the true nature of this reality. And yet, for every narrative that we find ourselves lost in, the lens through which we interpret the true nature of this thing we call reality, we are also confronted with a world of different and contrasting narratives. This is the source of that tension. That we have this universal experience of being human in a world filled with information, and yet also contrasting interpretive lenses. I think of Joyce’s contemplative narrative in The Homemade God;

“When someone dies or disappears, we can tell stories about only what might have been the case or what might have happened next. And perhaps it is simply a question of control, but it is easier to imagine the very worst than to allow a space in which several things might be true at once.” (The Homemade God by Rachel Joyce)

One of the questions this paradox, this tension seems to engage is, does this keep us at arms length from actual knowledge of this world, or is this somehow part of the process, the way in which the world that we inhabit can be known. Truly known. I think part of what my reading year has unpacked for me is, it is precisely because everyone sees through a lens that we can then also say that all people naturally believe that this world can be known in some way, shape or form. Not in the sense of aquiring scientific information but as an interpretive process we are all free to engage and must engage in order to be full participants. Participants who hold beliefs and convictions, beliefs and convinctions that we trust enough to allow us to step into something outside of ourselves. And indeed, even to go inwards and engage ourselves as well.

It is simply a matter of what world our lens is revealing and what the implications hold for our particpation in a world with the tensions of both Life and Death, ugliness and beauty, time and eternity. That’s the thing our differences engage. That’s the shared tension. That’s what it means to seek and then to be brave enough to also believe. It is the difference for example. between something like Hawkins old brain/new brain view in which reality is defined by technological advancement (A Thousand Brains), and David Bently Hart’s appeal to a metaphysical reality in which All Things are Full of Gods.Two different stories emerging from the same observed and experienced world.

One final practial note. It was in reading Mandy Smith’s Confessions of an Amateur Saint: The Christian Leader’s Journey from Self Sufficiency to Reliance on God, that I was left grappling with a very real example of this kind of tension. Entering into a new job informed by a contract containing a statement of (religious) beliefs. Having to confront the idea that we are at all times and in many ways living in a world shaped by such social contracts. The question this bring up for all of us is, where do we locate the integrity of a life in a world where we both find ourelves signing on to such contracts (figuratively or actual) while also upholding the tension of our necessary critiques and the nuances of our beliefs? Can we both sign our name and participate honestly in this world as those seeking after the ongoing revealing that life represents? In some ways we don’t really have a choice- this is how life works. And one of the things Smith helps liberate is that thought that if we enter into these “contracts” that we cannot actually live honestly. In fact, such a suggestion would leave us unable to live at all.