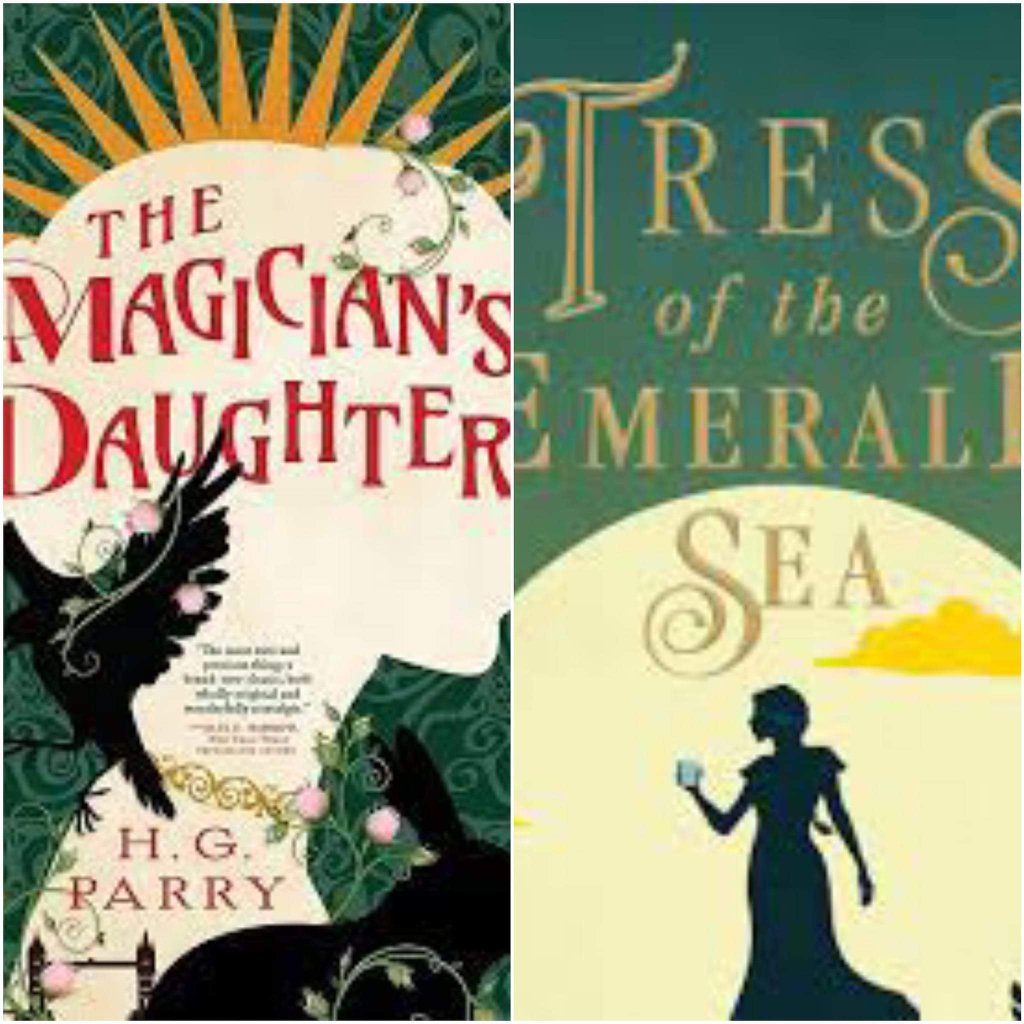

Reading Journal 2023: The Magicians Daughter by H.G. Parry, and Tress of the Emerald Sea by Brandon Sanderson

I paired a reading of Sanderson’s Tress of the Emerald Sea with H.G. Parry’s The Magicians Daughter. Tress was a recommend, The Magicians Daughter a blind buy. The synopsis seemed to suggest some potential shared qualities and interests, and they both appeared to occupy the YA genre or something slightly older. Thus the pairing. Turns out it couldn’t have been more perfect. Both stories focus on a central female protagonist who, as the books begin, have spent their lives in isolation on an island. In the case of Tress it is a fictionalized island reminiscent of somwhere like Ireland. In The Magicians Daughter it is set in Ireland. Both stories follow their protagonist off the island, albiet for different reasons, and both books detail a world that is governed by magic.

All of these shared points reflect what I appreciated about one and what I didn’t about the other. Of the two books, The Magicians Daughter is the one that stood out for me. In fact, it ended up being a new addition to my permenant shelves, which I save for those stories that I find especially impactful. Tress started off strong, but ultimately it faded, and sharply so, in the second half.

So what did I like/dislike? Part of what I need to concede with Tress is that it does gear younger, and intentionally so. Its protagonist is the type that you might expect from a teen novel, especially the way she is bound to the titular love interest. The set up does at least seem like its going for something a bit more ambitious, but the way Tress’ adventure plays out is essentially hampered by superficial motivations. Given the way the story merges from the intrigue and mysteries of this beginning into a full scale adventure into a world where the sea is made of dangerous spores and where this space is controlled by pirate ships and the like, the potential for this mysterious persona to be interesting falls by the wayside pretty quickly. Which makes the entire second half a slog, as its committed simply to world building, giving these underdeveloped characters an intersting landscape to exist within, but no compelling reason to navigate it.

The Magicians Daughter on the other hand takes the opposite route. It gears a bit older, but it also takes its time establishing the characters and a real sense of place. By the time she leaves the island I was able to feel its departure. The stakes also exist far beyond simple romantic interests. Here we find a world that once was fillled with magic and wonder and which has since lost its magic. From this unfolds a mystery- where did the magic go, how do they get it back, why does the magic matter and how does it operate, and how does all of this relate to the council which rules the lands and the cast of characters whom seemingly exist as its resistance, fighting back against its corruption. Parry has layered the story with different elements that allow the world building to unfold much more subtly and gradually than it does with Tress, letting the natural tension of its characters and its circumstance drive the plot forward.

The other issue with Tress is that it starts off by seemingly anchoring itself in a real world setting that just happens to have fantastical aspects. As the book pushes forward any sense of familiarity with the world these characters occupy goes out the window. It becomes more and more fantastical. Which is not a problem in and of itself, except that it required a readjustment after I entered into the story. Full disclosure- apparently this book fits into a larger universe of books I have not read, so that could have made a difference. I had allowed mysef to be drawn into one thing, and then it proved to be something very different, and that ultimately pulled me out of the story for a good quarter at least. In The Magicians Daughter, the realism and familiarity of the world they occupy is certainly filled with magic and is fantastical, but it never loses that sense of familiarity. This is a world just like our own, only it imagines such a world from the perspective of this magical source or power being the thing that gives it life. The strength of its story then is its ability to allow this to function as an allegory for the world we know. A world shrouded by darkness and which needs to recover the magic and wonder it once had. Its a story about hope that plays into many facets of our present day.

The other strength of the Magicians Daughter is the way the prose allows each character their own unique vantage point and struggle. While much of the mystery plays on these character’s identity and motivations being held in question, this never undercuts the value of the real time relationships and the relevance of their experiences shaping them in the moment. We are learning as we go, and everything that we learn becomes part of the necessary interpretive practice once the puzzle is fully put together. And even then, the book’s conclusion leaves plenty of room too for our imaginations to play this story further an outwards in our imagination. If Tress contains us as readers to the basics of its plot points, The Magicians Daughter opens us up to the expanse. It becomes a kind of fairy tale rooted in reality. A commentary on modernity where the power of myth has increasingly lost its force, leaving much of what we do without a necessary foundation. That this commentary reaches from the personal into the fabric of our social and political realities is certainly where it gains its full force of power and draw. An invitation to believe again that magic exists and has the power to transform the darkness of our world into light.