Lengthy car rides tend to translate into plenty of time getting lost in thought

Inspired by consecutive podcasts weighing in the mess that is the present day American Film Industry, I started to think back to the 2010’s, which was really when the whole streaming thing started to become a thing. Initially I was all in, being the one who was going around telling my friends to check out Netflix. It wasn’t that long after though that I started to question the way things were going, observing some of the ways it was “disrupting” the industry. I worried about it because I love film and care about the industry deeply, even living north of the border (as they say although our industry is unique, we are still very much operating in extreme close relationship to the AFI). I see art, and film as an artform, as an important and necessary facet of our lives, and more importantly our lives together. We are formed together through art, and art informs the way we are formed together.

Thus, around the mid part of the 2010’s I made a significant shift in my perspective based on what I was seeing and reading, going from Netflix advocate to the publically anointed “anti-netflix” guy. By and large, in nearly all of the places where I was attempting to raise the alarm bells I was dismissed as a crazy, hopped up on hyperbole and made to be synonymous with “old man yells at the cloud” memes (among other more vile things).

My theories were simple back then. Training people up to expect instant access any time they want at one low cost through a singular space that has exclusive rights to the art is not good for the art, the artists, or the industry. Further, training people up on forms of distracted viewing would lead to devaluing the artform and the decline of theaters. Along with that I suggested that, even if we like the convenience, the way streaming was disrupting the industry was not sustainable. The main response I got, and almost uniformly across the board, was people reminding me of the old system being something that needed to go and that this new system would figure things out.

I eventually backed out of the discourse to a large degree and sort of defaulted to the most reasonable expectation I could find, which was the potential of emerging services creating competition and hopefully accelerating necessary change, even if it meant needing to fight back against the expectations of viewers that the habits of streaming created in the first place. While it made some differences, it wasn’t nearly enough to tame the storm. Thus, especially after Covid, I doubled down on the only real support I felt I could genuinely give- going to the theater.

What I didn’t predict, although the likes of Spielberg did once upon a time, is the insanity that would follow the reopening of theaters. Never in my life had I experienced so many theater releases releasing on a weekly basis. Even seeing three a week I couldn’t keep up. I assumed this was a byproduct of the delays incurred by closures. And yet the trend has persisted, only now it seems to be by design, a response to an increasing number of box office failures, monetarily speaking. A perpetuating cycle that is not sustainable and is not good for the art, the artist and the viewer, even in a landscape that continues, in some respects, to make an astronomical number of films each and every year. It is easy for the few success stories to dominate the headlines (think Super Mario) and to cloud the plethora of struggles behind it (think Elemental).

Which brings me back to today and my long drive. What struck me is that here I was listening to the same pundits who spent years supporting the very same system they were now criticizing while wondering how it was that we got to where we are today. The signs were clear. None of this should be surprising. The present mess is a long ways to go just to come back to some of the basic value systems that we know to be true- systems that uphold necessary support for the art lead to greater appreciation for the art/artform, and greater appreciation for the art/artform is the best way to combat the sorts of expectations that streaming has created while also supporting artists/creatives (fair compensation being necessary) and investing in a landscape that is able to support smaller, independent players along with a whole industry filled with currently struggling creatives doing the creative work on the ground, writers included.

I am certainly standing in solidarity with the writers, whom typically have been the ones most likely to suffer from the present state of things. And their voice is simply representative of the larger systemic problem. I’m still afraid, and somewhat convinced, that the casualties will be large and significant on the other side of the shutdown, and more importantly largely unnecessary given how clear these issues were. But I’m also hopeful that smaller players (like A24 for example) can help lead the way to a healthier future. This is long past the streaming versus theater wars, which was such a shortsighted mantra. It’s not about anti anything. Rather, it’s about building an integrated system that genuinely supports the art, the artists, and the artform/industry.

Film Journal 2023: Cobweb

Film Journal 2023: Cobweb

Directed by Samuel Bodin

Such a fascinating film to unpack on both a technical and experiential level. Full disclosure: I don’t think I fully appreciated the ending. Given the journey this film takes us on (and it’s a journey), it doesn’t really bring that to a satisfying conclusion. At least on an initial viewing. That might change on a rewatch knowing what this story is and where the story goes

But I found the journey itself to be wholly interesting and engaging. While the central character is a young boy with, as it states, a “big” imagination, so much of this film revolves around how the Ditector positions his parents. Their presence is meant to ground the film on one hand while keeping the whole thing just ever so slightly off kilter at the same time. It employs a slow burn approach, which means a good half of this film operates in this largely undefined space built on a lack of clarity when it comes to who this family is and what the heck is going on. We get a smattering of traditional horror notes along the way, but, by design, this is meant to unsettle us with a sense of uncertainty regarding the potential threats out there and the threats lurking on the inside. What we know for certain is that there is something tangibly off with the kid, which is played through his less than ideal schoolyard experiences as well as his chronic nightmares/experiences at home. What we are meant to feel though, if undefinable in the moment, is that something is off with the bigger picture.

It is around the halfway point that things begin to come into view with a bit more clarity. Its here where the Director really begins to flex his horror muscles with some genuinely effective and creepy sequences. Loved his attention to the practical effects and the way he uses the camera movement to play with differing points of perspective. MSome really impressive work for a debut.

Taken together, these two halves do ultimately table some key questions regarding the larger story’s interest in the source of the horror. This is where the ending I think falls a bit short. The clarity of the second half needed to speak more directly to the experiences of the first half. It almost felt like the Director was so eager to get where he wanted to go that the journey itself becomes an afterthought. This leaves those questions swimming around with nothing concrete to attach itself to. Perhaps most notably this is felt with the ultimate development or transformation of the young boy, who struggles with the real world and translates this to the fears residing in his imagination. The pieces are there to break open his story and anchor it in a larger sense of reality concerning how it is that we both face and shape these fears, especially where it intersects with the trauma of our past,, but they are never fully pieced together.

Even with those imperfections this is nonetheless an exciting project that unearths an exciting new voice in the field of horror.

Film Journal 2023: Barbie

Film Journal 2023: Barbie

Directed by Greta Gerwig

If you’ve seen Gerwig’s previous films then you know she has a unique and signature style. Given that Little Women was a direct adaptation, then you also know her interest in potential subversion of the text/IP. Barbie comes out of the gate swinging, leaving little doubt that Gerwig is all in on the IP’s endless potential for color, fun, and over the top zaniness while also leaving little doubt that this is hers to shape and mold in line with her vision and her style. Unlike Little Women, where there is a history of adaptations and source material functioning as the necessary foundation of what becomes a larger conversation with and about the texts place in history, with Barbie the foundation is more an idea. If both Lady Bird and Little Women tackled the challenges of being a young woman growing up into the modern world, Barbie functions as a broader and often meta take on the systems themsleves, especially as it pertains to history.

It might seem weird to suggest that an IP like Barbie would function as a foundation for such lofty ideas, but Gerwig leaves little doubt that for careful readers of the text this is exactly what we would find. That she wraps this in a careful and respectful celebration of the iconic doll, and has a ton of fun doing so, is simply who she is and what she does so well. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Barbie is the way Gerwig has crafted a film that speaks across the lines of our constructed ideas of gender roles and expectations. She cleverly notes the irony inherent in the idea of a Barbie world where Ken is an afterthought and men are facing the oppressive and powerful forces of an alternative feminist imagination, and the real world governed as it is by the patriarchy. The film uses these constructed realities to explore the interplay between the messiness that the doll represents as both idea and ideology, caught between selling the promise of liberation on one hand and perpetuating stereotypical and impossible images of perfection on the other. True solutions to the problem must find a way to cut underneath or to run inbeteeen the clutter and the noise.

The film also embodies this conversation in a mother-daughter relationship from the real world, which allows Gerwig to explore the generational gap that exists between the idea and the evolution of an idea. Binding these two things together is the idea of “stereotypical” Barbie, played with gleeful commitment by Margot Robbie. The original idea set in contrast to the evolution. There is a line in the film uttered in its climatic moments that explores the relationship between “becoming” (changing and evolving and experiencing and growing in time) and “being” (those ideas or realities that stand outside of time and are eternal). This provides a fascinating exploration for how it is that we relate to the eternal (the idea) through these acts of becoming. I’m not sure Gerwig is quite able to flesh this out to the level that it needed in order to be really and fully substantive, and she ultimately takes some of the easy roads around what are in actuality big and messy and complicated ideas. This typically results in a tendency to romanticize mortality rather than facing its complications and conundrums head on. There is an irony that exists here in the fact that it is tackling the messiness of an idea (the perfect, stereotypical Barbie) by avoiding the full implications of a messy reality, but this is unfortunately a familiar characteristic of a lot of Hollywood films.

There is no doubt however that she is able to locate the emotional core that lies at the heart of the questions she is asking, and she does the work to make it visible and accessible. And the work she does to transcend the lines of our social constructions and speak to everyone at the same time has real payoff. Even further than that yet, Gosling’s iconic and off the rails performance as Ken, the nod to Barbie’s nostalgic pull, the incessant in film references to other films (there’s even some odes to Elf with its imaginative take on a journey between worlds and the search for ones bonded human), the exhuberant dance numbers, it all pays off by being a whole lot of fun. Especially with an interactive and hyped up crowd decked out in Barbie outfits.

Reading Journal 2023: John: Responding to the Incomparable Story of Jesus (New Testament Everyday Bible Study Series)

Reading Journal 2023: John: Responding to the Incomparable Story of Jesus (New Testament Everyday Bible Study Series)

Author: Scot Mcknight

Mcknight’s commentary on John is part of his ongoing Everyday Bible Series. These are accessible commentaries that aim to blend an emphasis on current scholarship and pastoral concern. By design, these commentaries go verse by verse, breaking passages into bite size and digestible chunks via chapter breaks that can encourage a daily devotional approach.

One of the great things about these commmentaries is how deep they manage to dig in a fairly short amount of time. The format does face some challenges given John’s lengh; all the others I have read, save for Acts, have been on the epistles, which are considerably shorter. Unlike Acts, the thematic weight and sheer breadth of John’s Gospel is a lot, and you can feel the attempts to wrestle it down to fit and serve its format. I do think he finds success, relying largely on teasing out the patterns and points of repitition, but this does demand a bit more work and investment on the part of the reader.

Mcknight begins by noting the uniqueness of the Gospels in terms of literary text and genre in the sccriptures. He notes how the closest parallels are portions of Moses’ biography in the OT, or the different viignettes of the key figures in Israels story. This distances the Gospels from the prophetic texts in terms of interests and focus, an important distinction given how the Gospels exist in the tall shadow of the prophetic history. It represents a shift from “what the prophets said” to an obsessive take on “what Jesus did”. Given the Gospel allegiances to ancient biography and the Caesar Gospels, this becomes one of its most distinctive elements. When one considers how absent this emphasis on what Jesus did is in Paul’s letters, it becomes an even bigger point of consideration.

Mcknight then moves to explore the counter-intuititive nature of John’s Gospel. He suggests that in common approaches we come to the text with “a good idea of who God is” and then ask how Jesus fits into that given the nature of his actions and words in the Gospel. What John wants us to do is gain a good idea of who Jesus is and ask how that fits in to our conceptions of God. This is how faith is formed and expressed in the Gospel of John, faith which operates in conjunction with belief, which in the ancient mindset is understood as “ongoing abiding in who (Jesus) is. For John this is what it means to enter into the grand narrative of the “logos” made flesh. The very logos whom tabernacled amongst us. Here it is important to note how John’s Gospel is composed to reflect a new Genesis, or a new creation text. Less overt to modern readers is how it is also designed around the story of a new exodus. Mcknight does a good job of anchoring us in the ancient story of Israel as we go, the purpose of the Gospel being “to promote believing” in this story.

There is no escaping the long history of anti-semitism and bigotry that follows John’s Gospel in the pages of history, and Mcknight faces that head on. And he tackles this by employing one of this most popular forms of exegesis- learning how to read the story backwards. Here the point and context for the Gospel is stated in 20:30-31 and its emphasis on belief as a whole journey, as the living of the Gospel story. It is within this story then that John is interested in connecting the logos to God by way of consecutively drawn out relationships- John the Baptist, the world, to the coommunity of faith. Here John is using a Greek term and idea (logos) to evoke the timeless and eternal nature of the story of Israel. The Logos in John doesn’t “descend upon or enter into Jesus, the Logos of God became the human nature Jesus bore.” This is crucial to understanding the way the text “baptizes” the Greek term in the Jewish story. The Logos is alligned with the creator. It is “the light” and the very source of life. And in John, the relationship between the baptizeer and the son becomes a key part of the structure in terms of how these relationships function as signposts. This becomes important too when it comes to John’s emphasis on the “world”. So often people read John to suggest God against the Jews and God against the world. Not surprisingly this then results in common perceptions within Reformed circles that John is suggesting that the flip side is God’s sovereign purpose in narrowing the emphasis of God’s love to a “chosen” and select few. The faithful. Those who believe. But this misses what John is saying altogether, which is precisely why we need to learn how to read the Gospel backwards. To hold the Gospels aim and interest in view as we navigate the particularities of Johhns language. In John’s Gospel the “I am nots” parallel the “I ams” as an internalized structure meant to reveal Godself in Jesus. The same applies to the way the Gospel functions as in inward critique (speaking to and from the inside) pointing outwards. What tends to happen is that Christians come to this Gospel and assume an external position looking from the outside in towards the Jews and the world and the non-elect. But if they truly understood the nature of the internal critique they would recognize that such a reading only condemns themselves. And yet the purpose of the Gospel is to believe in a much different truth and a much different story.

“Who Jesus is also changes what it means to be human.” This is why the “all” phrases matter so deeply to John. “to callJesus Messiah is to affirm him as the consummation of Israel’s story”, and this consummation understands that this story is one that speaks to and for the world. We either trust this story or we don’t, and both postions have implications for how we then see not just the world around us, but what the nature of humanity and God. This is what is at the heart of the high priestly prayer. The implications of this, according to John, is quite literally what is behind the reactions to Jesus’ words and actions which send him to the cross. That Jesus is God afffects everything else. “What surprises the disciples in the midst of their chaos is Jesus’ word that they know the way, for they seem to think they don’t.” This is the very thing that should suprise us as readers. And its a surprise, if John has his way, something he hopes to root in the arrival of the Spirit, that should unsettle and disorient us from one perspective into another based on its revelatory force. “To serve Jesus” in John “means walking toward the cross of his death, but with the consciousness that the “Father will honor” that way of life. Not just honor, but redeem in the truth of Jesus’ resurrection and ascencion. A truth that can only truly be underestood in the paatterns and motifs of the story of Israel. A story that is for the world, not against it.

Reading Journal 2023: The Desolations of Devil’s Acre

Reading Journal 2023: The Desolations of Devil’s Acre

Author: Ransom Riggs

This final book in the beloved series, and one I was finally able to check off after numerous efforts to pick up and finish (not due to the book, but due to getting distracted by other novels), ends the now sprawling tale in what arguably could be said the only way it rightly could; by bringing us back full circle to where we started. If the individual books reflect different levels of good to great, The Desolution of Devil’s Acre demonstrates that the strength is in the whole. It was sad to see my time with these characters and in this world go, but satisfying to see Riggs committed to bringing resolution to every plot line and character that the series has encountered on the journey.

The previous books were noted for their abililty to take the contained stories of the early entries and use that to break the world wide open. In Desolution the stakes are at their hightest, but things are also dialed back down into the central characters whom form (and inform) the story’s heart- Jacob, Noor. Hollowgasts, Caul and Miss Perigrine. The book strikes a comparitively intimate tone in this regard, but one that acts as the stepping stone into the larger world of Peculiars. Because as has been made clear, they are who they are together. The arc of these individuals is largely attached to the community; Devils’ Acre if you will.

Riggs stays commited to the central plot device, the real world pictures taken by anonymous photographers which inspire and create the different plot turns in each book. By now it is second nature and so ingrained in the process that it is easy to simply read these photos naturally into the story without being distracted by it. One of the effects this has is it shapes our imagination of who these characters are, as these are flesh and blood images that define who these characters look like within the story. It also tends to take a fantastical story and ground it in that flesh and blood imagery, although even the grounded and real world images require an interpretive lens, which is part of the device that Riggs uses to push the boundaries of what we see and read. This is what sets this series apart from other YA series, and there is little doubt this is a huge part of its charm and effectiveness, even this many books in.

Of course, it should go without saying that if you’ve made it this far in the series you are bound to needing to finish it, and rightly so. Rest assured if you are like me and dragging your feet unecessarily despite an eagerness to return to this world one last time, I think this ending will leave you satisfied. If you have yet to read even a single book in the series, I will say that uncertainty in the early going (I was on the fence with the first two books) proves worth the investment as the series goes on. It only gets better as it goes.

Film Journal 2023: Oppenheimer

Film Journal 2023: Oppenheimer

Directed by Christopher Nolan

Every so often a film comes around that feels impossible to describe in its details but also feels subsequently monumental in its presence. Oppenheimer occupies this space, with the only true certainty I could glean from it being that I was in the presence of something profound and excpetional.

To suggest that this should come as no surprise given the pedigree of its Director is to sell this film short as arguably Nolan’s best work to date and, in other ways, a return to form. By which I mean his inention to dial things back, which feels like an oxymoron given the pure scale of Oppenheimer’s story, and focus on the conversational and dialogue driven nature of the script rather than the visual spectacle. In truth, this actually makes the visual direction on display here stand out all the more with its allegiance to large screen Imax format, black and white/color contrasts, and a subtle visual storytelling approach. Where this perhaps gets the most mileage is in the way he manages to weave a universal, cosmic narrative reach with the intracacies of and its interest in demythologizing a larger than life character, ultimately locating the intimacies of such world shaping moments. Every ounce of this not only feels relevant and important to our present moment, translating across different scenarios and premises big and small, it feels meant to unsettle individual complacency concering conceptions of good and evil.

So much of this also feels like a throwback to an older cinematic style where the simple, barebones and grassroots level backroom drama carries the films undeniable charge and tension on its shoulders. The sort where it is easy to feel transported to a world ripe with a ferevent anticipation and optimism colored and cloaked by a heavily disguised sense of fear. In Oppenheimer, to say that the world hangs in the balance is to feel all the push and pull of its titular stars personal and familial crisis. That is what makes it so powerful as an experience.

Structurally speaking, which is one of Nolan’s greatest attributes and strengths, the films narrative finds a way to weave its 3 hour runtime into a fascainting fusion of narrative contrasts. On one hand a good section of this film is narrowed in on the progression of events that lead to the successful testing of the atomic bomb. This features and culminates in some of the most invigorating and edge of your seat cinematic moments in recent memory. The third act then revists this sequence of events from the perspective of an unfolding and working political thriller/mystery. Suddenly all the sublte work the film has been doing to build and establish the handful of characters as layered and dynamic and complex comes to fruition, effortlessly lending its ground work to an even more explosive finale. It might feel or seem like a daring move to structure the film in this way, but the true magic of the narrative structure comes from the way Nolan has been using a well formed set of moral and even spiritual questions to build out an overarching thematic interest, binding these two sections together with a powerful adherence to the moral quandry at its heart and its appeal to not simply the philosophical questions but to the relevance of such questions to its assumed human responsibility. A responsibility to ask the right questions. A responsiblity to see how these questions play out in the different aspects of our lives.

And let me just say, the film is chalk full of great performances, and everything in this film should be challenging for their respective Oscar categrories in 2024, from score to cinematography to script to production. But is there anything more memorable here than the handful of scenes between Oppenheimer and Einstein? The film reaches moments of transcendence throughout, but it was in these moments that the astounding nature of this achievement really struck me with full force.

Book Journal 2023: Flood and Fury: Old Testament Violence and The Shalom of God

Book Journal 2023: Flood and Fury: Old Testament Violence and The Shalom of God

Author: Matthew Lynch

The tagline on the back cover poses the question “what do we do with a God who enacts and condones violence”. Narrowing in on two of the most essential narratives in the Bible associated with violence- the flood story and the Canannite conquest- he works to transform that question into one more in tune with how scripture itself functions as both a sacred and literary work. If the above question is relevant to many of us today attempting to engage this work as a cross cultural movement into an unfamiliar language and worldview, learning the questions the authors and readers of scripture were asking in their world can be helpful in navigating the “challenge of violence in scripture”.

There is a good deal in Lynch’s analysis of these two central narratives that was familiar to me in terms of approach and information, albeit being one of the most concise and accessible treatments of these approaches and ideas that I have come across in a good while. And then there were some wonderful surprises. Some truly paradigm shifting surprises that left me wishing I could put this in the hands of as many people as possible. This was especially true when it came to the conquest narratives. I’ve spent a whole lot less time there than I have with the flood narrative, so that’s where I was most fully engaged.

A quick and cursory summation: central to his claims about these texts is the basic concession that part of the challenge of engaging the text is the existence of contrasting views inherent within the text operating in dialogue. This is of course the result of differing points of perspective being contained and retained and preserved with intention on the part of the Biblical editors. One of the central concerns that emerges from this process is, if God indeed spoke into and acted within history, how does this shape, and indeed reshape their understanding of their present circumstance when it comes to knowing who God is by the way God acts in and for the world.

This becomes especially complex once we begin to contrast shifting points in Israel’s own formation, locating within their story majority-minority points of view. This becomes a stepping point for navigating an important facet of scripture for us reading from our own vantage point as foreigners “into” the culture and language of their day; the role of internal critique. This becomes hugely important for engaging scripture from the outside looking in, as so often the tendency is to assume our role as judge and jury of the other, and such an act of othering, of which assumptions of our being “more” evolved and civilized and them more archaic belongs, is the best way for us to ensure that we miss and misappropriate what the text is doing in its world. A crucial point of perspective is to remember the movement present in the biblical narrative- enslavement, liberation, exile- and to understand that someone looking at this story from the point of exile is to going to be asking particular questions that a liberated or enslaved peope are not. When it comes to being good readers of scripture, and when it comes to learning how to allow these stories to shape us from our present vantage point this side of Jesus’ resurrection, we have to allow these different realities to exist in conversation.

One example when it comes to being good readers of Joshua. Noting how it speaks from the perspective of having arrived in the land and having been unsettled from the land, and how this perspective writes, using an intentional literary design, the “conquest” story in the light of the Exodus narrative, can help bind us to the bigger picture of a people contending with both promise and failure. This only becomes more apparent when connecting the conquest with the flood narrative, illuminating how it was that the ancient readers and authors saw a world to be in contention with the enslaving “spiritual powers”. This plays the connection between Joshua and the Exodus in direct relationship to the true conflict. It also gives us a way of teasing out how it is that we make sense of seeming points of contention when it comes to violent acts commanded by and attributed to the hand of God and a voice that witnesses to the character of God pointing to a different and opposing way of acting in and for the world, including the Canannites. If God did indeed speak into and act within the world in a revelatory fashion (as their convictions held to be), the question that follows, in line with the flood story (itself connecting us back to Geneis 1-5), is how does this character shape the way we live together in our present context. This is what we find in careful readings of the ever changing rules that follow an established people being prepared to take residence in the land within a world filled with violence. As readers of scripture it might feel puzzling at first glance to imagine a seemingly violent text being opposed to such violence, and yet as careful readers such a vision can come alive in transformative ways when we become attune to the larger narrative at play. Not least of which is reckoning the “”liturgical” presence of Joshua, a liturgy bent not on the story of displacing a people but in displacing the idols that hold the world in the grip of violence. Joshua on this front becomes a story of the completed Exodus, one that leads straight into the reality of exile on the basis of these same idols shadowing the greater vision of a liberated creation. Which of course leads to a new Joshua (Jesus), which careful readers can note is told through a Gospel story patterned after the Exodus and the Exile, the very thing that translates it as a “new covenant” story. A completion of both stories brought up together in God’s liberating work for the whole of creation.

A brilliant book, which blends important scholarly interest with pastoral intent. Especially formative for those who struggle to reconcile the sacredness of scripture with pertinent and important questions about the problem of its seeming violent depiction of God. It appeals to a narrative approach mixed with literary and historical criticism, but in a way that upholds the central conviction in the revelatory act of God in and for the world. It holds scripture as sacred, and is intently interested in the question of who God is based on how God acts in and for the world. The character of God should be at the forefront of the narrative, and when we allow the text to speak on its own terms it should draw us closer to knowledge of who this God is. Books like this are an extremely helpful resource then for learning how to become better readers and more faithful adherents to the story contained within in.

Film Journal 2023: Godless: The Eastfield Exorcism

Film Journal 2023: Godless: The Eastfield Exorcism

Directed by Nick Kozakis

A gut punch. Not something I expected from an exorcism film that, for all appearances, seems like your run of the mill genre film.

I don’t know how it was pulled off, but the way the Director tows the line between retaining a respect for religion and faith while digging deep into the potential of its abuses was quite profound. This will leave you unsettled, uncertain, angry. All sorts of emotions.

Equally impressive how it uses elements of the genre, employing many of the classic staples of horror to evoke scares and an entertaining ride, to bring out something so rooted in the real, earthy nature of its context.

This would make a fascinating double feature with the Pope’s Exorcist, or even the Exoricsm of Emily Rose. So much potential for discussion. And I say that as someone of faith. This is the sort of dialogue that faith needs.

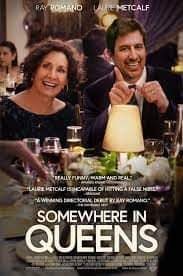

Film Journal 2023: Somewhere In Queens

Film Journal 2023: Somewhere In Queens

Directed by Ray Romano

It’s not unusual to talk about right time, right place when it comes to viewing film. This is the subjective side of film critique, and I think its fair to say this carries more weight than any objective measure. True objectivity is, after all, something of a fallacy, and most objective critique remains in the realm of social construct.

If it’s true, and time and place can play a central role in informing a given experience with film, the fact that the ending to Romano’s directorial debut hit me like a ton of bricks probably reveals more about my life in this present moment than it does about the film itself. I needed to hear its affirming message,

The film certainly earns the emotional beats however, soaked as it is in Romanos penchant dry humor. He smartly allows the film enough breathing space for the whole cast to develop as fully fleshed out characters, each with their own distinct personalities. The strength of the film is in the way these different characters come together, clashing at points and complimenting at others. It offers an intimate and endearing portrait of famijy, exploring generational dynamics, the role of tradition, trauma, expectations, healing, forgiveness. Within that we get a film that astutely navigates the simple ebb and flow of every day life, where small things become big and big things are made small within the context of familial connection. From this comes these striking redemptive moments within the individual characters, each traversing their own paths through these shared spaces.

Just don’t be surprised if your right time, right place elicits some necessary tears.

Film Journal 2023: The Eight Mountains

Film Journal 2023: The Eight Mountains

Directed by Felix van Groeningen and Charlotte Vandermeersch

I remember when Broken Circle Breakdown released I was championing it everywhere I went to as many people as possible. I found the films writing and it’s thematic focus, along with the central performances, to be a profound revelation, especially considering it was the Directors debut.

I had been eagerly awaiting his follow up for a while, excited to see what he would come up with next. Perhaps the most striking feature of The Eight Mountains is the way it reframed a similar dedication to the performances and the thematic weight within a much broader cinematic presence and scope. The story is here is sweeping, tracking its main character, a young boy named Pietro from Turin, not only through time, but through the grand backdrop of the mountains employing a contrast of weighty, existential questions and intimate concern.

There is a cast of characters present in the film, all of whom form the backdrop of Pietro’s journey. Given that Pietro’s voice, reflecting on his life’s story from a time and space years removed, is the narrator for the film, we get all of these stories from his perspective. If I had a slight criticism, it would be that this limits our ability to really get to know these supporting characters from their own points of view. This is especially pertinent when it comes to Bruno, a childhood friendship which ends up experiencing distance after Pietro’s father offers to adopt him and aid him in his future studies. Much of the film is interested in the clash of worlds that this relationship represents, Bruno introducing and opening up Pietro to his upbringing in the mountains away from the city, and Pietro challenging Bruno with his more cultured outlook. As the film unfolds, the early action of his father in adopting Bruno from the mountains and anchoring him in the idea of the city becomes a source of conflict between father and son, which, as we also come to know early in the film, expresses itself through this same necessary clash between mountain space and cultural realties.

Thematically speaking, these things become fully realized in the symbolism of the eight mountains, an ancient cosmological image in Buddhism and Indian philosophy. It is the thrust of this imagery, which surfaces at a crucial point in the film as a named concept, which moves the clash between lifelong friends and estranged father and son into that cosmological vantage point. The intimacy of the human struggle becomes a matter of existential concern.

The way that the camera captures the mountainscape is similar to the way it captures the intricacies of the city. It imagines it in minute details, lakes becoming meeting places, rocks becoming destination points, mountains becoming buildings and skyscrapers grassy outlooks neighborhoods. Which is what makes the mountain both an escape from the world and a meeting place within the world, an idea that presents a fascinating juxtaposition. What it means to be alone, what it means to be togther, two portraits of existence and meaning that loom large against lifes persistent struggle. And the film never answers this tension, rather it lets it linger.

What it means to make a life, or to make a succesful life, is a question very much ingrained into the fabric of this story. To make a life against the struggles then becomes the focal point of the films own deep rooted longing and desire for some sort of reconciliation. For me, my mind kept wandering back to the story of the Israelites in the Judeo-Christian scriptures, and more specially the metaphor of the nation being depicted as a first born son. I reflected on the questions we find the nation asking in the midst of their own exile. At one point, Pietro wonders through the narration, “what do I do with a failed dream and a promise that is not my own.” It’s one thing to say that the failed dream is mine. It’s quite another to say that my life is shaped by the failed dream of another for me. This points to that idea that we are intimately connected to the story of another, and when the dreams for us by those whom believe in us and see us for who we truly are fail, that’s when our ability to trust this world and the nature of our existence really gets rocked. For Israel, it was the seeming failure of God’s promise to make right what is wrong in the world that held them captive to their exile, chasing after all manner of idols in exchange. For Pietro, it is the failure of his father’s dreams that leads him and Bruno to a kind of shared exile.

And yet, the story of Jesus intersects with this narrative in a powerful way, ringing through the noise, and in the case of this film a lot of silence, to remind us that the promise is not ours, it is rather found in the faithfulness of God. It is in Jesus that we find the promise fulfilled, just as Pietro finds on his journey the fulfilled promises of another.

Subsequently, I also found a lot of prodigal son story embedded into the subtext of this film, framing the different relationships from within their differing vantage points, the two childhood friends often swapping roles. The notion that time and distance does not disconnect them from the dream becomes a powerful throughline. Ultimately though it is about the friendship that develops between these two kids become grown men. Given that we see this from Pietro’s perspective, the film has a way of moving quickly through time when we find him speaking with the greatest degree of confidence about his past, and then slowing down at points that force him to stop and reflect and linger, often on the mountaintop. In that sense this is a very spiritually laden film that pays a lot of attention to changing and shifting vantage points in space and time, much like we might find moving from the low ground of civilization to the silence of the peak.

There is much more that the Director embeds into that idea that pays off nicely within the larger narrative, but stripping it down to its most essential and basic idea, The Eight Mountains wants us to consider how the center remains even as one traverses the circle that makes up the broader world and experiences around it (to use the framing device). Eastern philosophy tends to frame it’s stories in circular terms, but here the Director adds a subsequent thought; Can we return to where we were once we’ve left to explore the circle? Certainly the temptation is there to want to do just that. And there is a sense in which the journey to the circle is meant to bring us back to where we started, only as different and transformed persons. Perhaps then what the Director is getting at is that the promise inevitably points us towards something new, something transformed. To return to where we started is not only to return as someone new, but to return to a place that must look and feel different as well. Further yet, it is to look forward with a different frame of reference, just as we do within the story of the person and work of Jesus. But we do so with that foundation firmly in place. The thing that reminds us that there is a dream and that the promise is being carried through the belief and action of another, a belief and action that claims the power to shape who we are and what this world is.