Back in December of 2019, I came up with the idea of travelling the world through film in 2020 and tagged it filmtravels2020. This would include compiling and watching films from that Country where available, researching that Country’s film history, and doing a reflection on what I learned where time allowed.

To be honest, when I came up with the idea I had no idea how far I would get with this exercise. It felt a bit ambitious, and tracking down films from all of these different Countries was certainly going to represent a challenge. But then Covid hit, and the film travels not only seemed that much more doable, but also timely. When you can’t actually go anywhere physically, what better way to see the world than through their films?

While I’m certain there are more Countries represented in the lengthy list of films I was able to watch in 2020, in terms of intention I tallied my final log as visiting 25 Countries in 12 months. Over these 12 months I feel I learned a lot about how the film industry works not just here in my own Country, but on a global scale, making this endeavor a worthwhile investment

TOP FILMS FROM MY TRAVELS AROUND THE WORLD

For each Country that I visited, I tallied and ranked my list of films. I broke this down by Country below listing my top 3 films from each Country with a brief descriptive and spotlighting one worthwhile title that I think captures the essence of that Country. The ones not included here are Ukraine, Philippines, and India.

AUSTRALIA

Mad Max: Fury Road

The Great Gatsby

Sweet Country

In the spotlight: Hotel Sorrento

One of challenges the Australian film industry has faced over the years is its over reliance on international (read: American) features. This has made it a challenge for getting Austalians to actually watch Australian films, which plays an important role in telling the story of their culture. Hotel Sorrento sheds a light on this disconnect by telling the story of a writer who wrote a book about the Australia she left behind and returns to her homeland to attempt to reconcile its modern story with the story from her memory. This mirrors the story of the Director who was trying to recapture a sense of Australian identity through this film, and the result is a passionate love letter to her country along with an examination of the relationship between art, the people and culture.

ITALY

Cinema Paradiso

Bicycle Thieves

Tree of Wooden Clogs

In the Spotlight: Journey to Italy

The list of Italian films that I could have chosen to highlight is vast. Failing to mention classic works like Umberto D. and even the more modern Happy as Lazzaro feels like a travesty. It was my favorite Country to visit, and their role in shaping the film industry on a global front while retaining their unique sense of of culture is nothing short of astonishing. The reason I chose Journey to Italy to highlight is because it functions as the perfect film both for gaining a sense of Italian culture and Countryside and for getting to know the rich legacy of Italian neo-realism. The way it gives us the perspective of these keen eyed, curious tourists brings Italy to life in its romanticized and idealized form without ever losing sight of the authentic markings of what is a very real and inhabited culture.

TAIWAN

The Tiime to Live and the Time to Die

A Brighter Summer Day

Yi Yi

In the spotlight: Eat Drink Man Woman

One of the most amazing aspects of Taiwanese film is its connection to a real sense of place. You can note much of the symmetry similar to Japanese film, along with it’s tendency to balance this framing of intiimate living quarters with the larger backdrop of the culture, country or city. Taiwanese films tend to be much quieter and much more specific than Japanese films though despite these similarities, something you can see even in one of it’s most recent works, this years A Sun, a sauntering journey through the life of a fractured family. I easily could have picked any of the above films to spotlight as they all shed light on a specific moment in Taiwan’s history, including the epic A City of Sadness. The reason I chose Eat Drink Man Woman is because of the unique way in which it offers us a sense of the culture through its food. The human drama is just as compelling, but there was something special about considering the connections between this family through the simple nature of dish, of the cuisine that helps them locate themselves in the comfot and familiarity of their traditions.

SOUTH KOREA

The Wailing

The World of Us

Secret Sunshine

In the Spotlight: A Taxi Driver

America was thankfully awoken this past year to the wonder of South Korean film through the immensly popular Parasite, a film that managed to find its cultural moment in an unparalleled fashion. Which is great, because there are rich treasures that await anyone willing to dive into the Country’s rich catalogue of directers and films. One of these films is Jang Hoon’s A Taxi Driver, a film that is equal parts devastating and heartwarming as it journey’s through South Korea at a pivotal point in their history. What might have been most compelling to me about this film is the way it shed light on this Korean man’s willingness to see his collective family (his community) as valued as his immediate family. This feels like an afront to Western sensibitilies where the value of the individual tends to be elevated above all, but this is part of the power of watching international films is that it can open you up to to the sensibilities, world views and assumptions of other cultures.

IRAN

Certified Copy

A Seperation

Children of Heaven

In the spotlight: 3 Faces

It was tough to single out one film that could accurately reflect Iranian film history and culture. Iran proved to be such a fascinating culture to travel through precisely because of the ways in which so many Iranian Directors are writing Iranian stories from the outside looking in. Iran’s history has this interesting mix of progressivism and traditionalism that are at once in contest but also seemingly in conversation. And while it would be impossible to talk about Iran without going through Asghar Farhadi, represnted above in the spectacular and emotional film A Seperation, Farhadi is far from the only filmmaker doing incredible work. I toyed with the earlier classic The Cow, a film that brings Iranian culture front and center, and one of my favorites, Radio Dreams, which tells the story of an Iranian writer using music as a way into the Country’s ethos. But I landed on more recent film called 3 Faces because of its ability to shed light on the plight of women in Iranian cinema, and likwise the incredible strength Iranian women have had in finding and retaining their voice.

FRANCE

Certified Copy

Au Hasard Bauthazar

The 400 Blows

In the spotlight: Playtime

In contest with Italy as one of the most relevant film cultures in cinema’s history, France’s lengthy list of films feels as endless as its influence. They have consistently demonstrated an ability to experiment while also valuing the artform as something accessible, culturally specific and universally applicable. Perhaps there is no greater example of this than the joyous romp through Paris that is Jacques Tati’s Playtime. The interest in capturing a place in time and amidst change is as brilliantly imagined as it is thrilling to experience.

SPAIN

The Skin I Live In

The Orphanage

Timecrimes

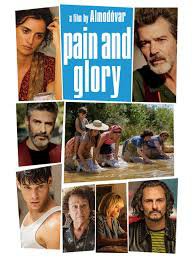

In the spotlight: Pain and Glory

As history goes, often understanding the influences of one place can help shed light on the character of another. This can come from the reality of conquest and colonization. It can also be because of the ways in which certain cultural trends flowing inwards came to define a dominant Country’s own ethos. Spain is both of these things, being a window into much of South America while also understanding itself through the influences of surrounding Countries, including Fance and Italy. Although Spanish film certainly reaches further than Antonio Banderas and Pedro Almmodovar, it is near impossible to overlook their presence in the local industry and abroad. Pain and Glory is their most recent collaboration, and it is not only visually wonderful and ambitious in its narrative structure, it is a window into the story of the Director, shedding light on what it is to live and embody Spanish culture

MEXICO

Pans Labyrinth

Tigers Are Not Afriad

Amores Perro

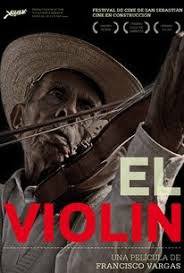

In the spotlight: El Violin

Del Toro is my favorite Director of all time so it would be easy for me to highlight any of his work as a staple of the Mexican cinematic identity, but one of the Mexican films I saw in my travels that blew me away in its ability to narrow in on the culture’s nuances and sensibiltiies is El Violin (The Violin). It takes place in an unnamed Latin American country that clearly is meant to symbolize Mexico, and by telling its story with a generational focus it is able to give us a picture of the Country and its challenges and its people that feels more aware and intimate than any other film I saw on my travels.

SOUTH AMERICA

The Film Critic

Behind the Sun

Wild Tales

Embrace the Serpent

Aquarius

Monos

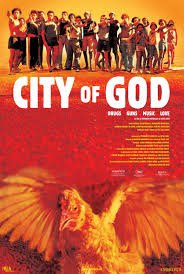

In the Spotlight: City of God

I included five films here because the area encompassed by South America is vast and diverse. I narrowed it down because I included it as a collective body of films in my travels while researching the distinct cultural flavors of each Country during my travels. The unifying language of revolution runs through these Countries, with another common narrative being Mexico’s distinguishing presence sheltering them from the invading force of the American Hollywood industry. There is a more modern presence in the film industries I encountered, and thus much of the films available are from this perspective. City of God actually tells a story from the 80’s, but it is without a doubt the film that comes to mind when I think of South America. It tells the story of a place, but in the way it focuses on the people helps to make this a great window into this exercise of learning to see the world and struggle through the eyes of others.

DENMARK

Ordet

The Hunt

As it is in Heaven

In the Spotlight: Pelle The Conqueror

For as interconnected as all of the scandinavian/eureopean industries are, it was also a lot of fun getting to know some of the distinctives that set them apart. As I learned, much of this has to do with how events such as the war impacted the Countries in different ways, with Denmark’s history bearing more weight to this end than a place like Iceland or Sweden. What also becomes very aware when moving through Denmark’s cinematic history is an emphasis on the rural/urban relationship, with Pelle The Conqueror being a distinct example of a film that sheds light on the intimate nature of this relationship as one full of hope and struggle, particiticularly from the eyes of an immigrant family.

POLAND

Ida

The Mill and the Cross

Loving Vincent

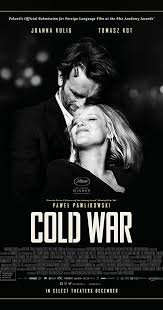

In the Spotlight: Cold War

I loved reading about the journey of Poland through the history of its cinema. It would be nice to read of these industries as a unified story of its birth, its development and its success, but that is not the story of every industry. Poland’s struggles are a great example of how a Country’s film industry can both mirror and impact a Country’s socio poliitical reality and its sense of identity. The films that have emerged from this struggle, especially those who have managed to gain an international presence, have proved to hold immense power as cinematic storytelling. Cold War is no excpetion. From the Director of Ida, it really takes us inside Polish culture in a way that feels honest and deeply connected. It’s a beautiful film on a visual and narrative level, but it is the smaller things like the music and the people and the setting that made this one so memorable. Truly felt like I went on a journey there and back.

Germany

Phoneix

Stations of the Cross

The Last Laugh (1924)

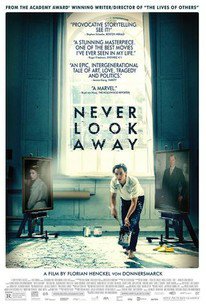

In the Spotlight: Never Look Away

There is a wonderful war film named Land of Mine that tells the story of a particular group of soldiers in post war Germany. It’s one of the best war films I’ve seen this year, told with humanity and tension. The film that best captures Germany to me though is the recent Never Look Away. It’s emphasis on the relationship between culture and art not only helps to shed a light on the German people and their heritage and history, it speaks to the German Expressionism that came to define its long cinematic heritage. One of the challenges for Germany is finding a way to tell their stories that doesn’t simply do away with or dwell on the darkness of its past. Making their past a part of their fabric while also capturing a people able to emerge from those shadows in a renewed sense of reform is what these more modern films aim to do, and thankfully they have a rich history reaching back to the ealry 1900’s to pull from for inspiration.

JAPAN

Departures

Millennieum Actress

Tokyo Story

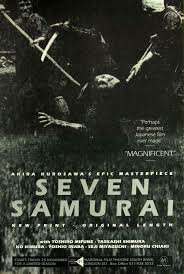

In the Spotlight: Seven Samurai

Japan was a relatively easy Country to travel through because of its strong presence abroad in North America, a well established industry, and a wealth of great and important films to see. This accessibility shouldn’t neglect the necessary conversation about Japanese culture though. Researching Japan’s film industry revealed a complicated relationship, especially where it exists between Japan and China and Japan and America, two economic giants. The same relationship that makes Japanese culture so accessible in North America leads to necessary diligence in assuring that their film industry doesn’t simply get assimilated into foreign ideas and structures. The biggest way they have done this is by using their films to anchor their identity in their sense of history, which reaches much further back than America. This history then translates into a sense of celebrated identity. This is the story that surrounds the making of Seven Samurai, a film that intended to break into the American industry by telling the Japanese story. It remains one of the most well known international features and one of the great classics of Japanese cinema.

CHINA

Ash is Purest White

Shadow

Long Journey Into Night

In the Spotlight: The Assassin

China’s industry is a discussion of seeming contradiction. It mirrors the American industry in may ways, dividing itself by it’s wealth of high budget blockbusters and historical dramas/high art. The overall aesthetic of Chinese films tends to be quite different than Taiwan despite the relationship between the two, with China’s film’s being busier with higher budgets and a more sweeping sense of history. The Assassin is a great example of this kind of film on the high art end of things. It’s a beautifully drawn epic that is rich in history and features expansive landscapes. It offers great insight into the cultural nuances as well, entrenched in the tradtion, worldview and cultural practices.

SWEDEN

Wild Strawberries

Let the Right One In

The Sacrifice

In the Spotlight) Force Majeure

One of the reasons I chose to spotlight Force Majeure in light of Ingmar Bergman’s illustrious and storied career is because of the opprotunity it gave me this year to compare the Swedish version with the American remake. This is a window into the specific ways in which two different cultures can approach the same narrative with an entirely different set of questions and concerns in mind. The existenstial nature of Force Majeure that is willing to sit in the tension stands as a contrast to the need for the American version to present its story as a more progressive structure with something concrete to say. The collective focus of the original also stands in constrast with the individualism of the remake. This existential quality is of course written all over the Swedish culture, with The Sacrifice being another great example. These films are always challenging, and offer great insight into the point of view of a culture and their experiences.

I also need to give a nod to a Swedish film called The Phantom Carriage. It’s such a great window into the Swedish landscape and culture, a film that utilizes its sense of place and time as well.

NORWAY

A Man Called Ove

Oslo, August 31st

The 12th Man

In the Spotlight: King of Devil’s Island

Compared to other European Countries, Norway’s film industry didn’t develop until much later, putting it’s development in line with World War 2 and thus putting it in a good position to recreate itself in the post war period. Documentaries and documentary style is big in Norway with the later developments following after the French New Wave and American modernist movements. The stories that did emerge were a mix of culturally dark material, cynicism, and social commentary. The King of Devil’s Island is a good example of these kinds of qualities, especially given how it tells a part of Norway’s history, but with a modernist flare for also telling an entertaining story.

IRELAND

Brooklyn

Calvary

Hunger

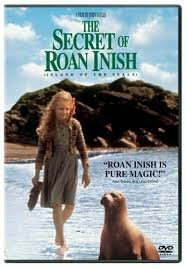

In the Spotlight: The Secret of Roan Inish

Anyone familiar with Ireland and Irish heritage will know that Ireland knows how to tell a good story. It’s written into their DNA, and although Irish film are entrenched in social reform and resistance, one doesn’t need to look far to find the beauty of their tradition, their land and their people being captured through their film. The Secret of Roan Inish is a great example of this kind of magical and often highly romatic storytelling. It sweeps you away into is lore and asks you to imagine a world where the secrets of the land and their lives as people exist in an intimate and expressive relationship, always ready to reveal itself to the other in its necessary timing.

UK

The Souvenir

Never Let Me Go

A Matter of Life and Death

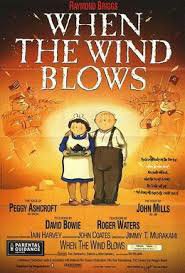

In the Spotlight: When the Wind Blows

The U.K. isn’t exactly the biggest leap from my home Country of Canada, but there are still some very specific differences that emerge in terms of culture. The uninhibited nature of Canadian films which tend to be small in focus and big on that northern anything goes mentality, gives way to a slightly more high minded and sophisticated brand of film. When the Wind Blows is a perfect example of this kind of sophistication, which displays this same kind of uninhibited appraoch just with a greater rootedness in their history and intellectual vigor. All of the loveliness of the Biritish spirit comes alive in this animated film, while its dark edges also refuse to be polished. You get the sense that stories like these emerge from somwhere concrete and visible, something that British history is able to afford its films in a very real way.

AFRICA

A Screaming Man

Atlantics

Cairo Station

In the Spotlight: I Am Not A Witch

Not unlike my trip through South America, my trip through Africa brought together diverse cultures with a common identity and experience. The reason African cinema has taken so long to develop mirrors the reasons for its current resurgence and development- colonization and oppression that worked to disconnect them from their story. Building their film industry means recovering and telling their story, which is precisely what they have set out to do. There is a celebratory nature to films from South Africa that is aware of its past but also hopeful for its future, and gaining this perspective is a big part of what is driving these storytellers forward. Being able to capature this on film through language, experience, worldview, spiritual belief systems, and pariticular politics and revolutionaries represents a world of untapped potential ready to take visual form. The harrowing feature I Am Not a Witch takes us inside a culture and language in a way that gives it presence, urgency and life. It’s a beatuful if difficult portrait of a people and their struggle.

RUSSIA

Leviathan/The Return/Loveless/Banishment

Beanpole

Hard to Be a God

In the spotlight: How I ended This Summer

Cold and harsh might be a recognizable distinctive of Russian culture, but it is also highly intellectual. It would be rare to encounter a serious Russian film that veers towards the superficial, and many of them are intently interested in the question of human worth, especially as it has something to say about hardship and struggle. What I like about How I Ended This Summer, even if it would be impossible to speak of Russia without acknowledging my favorite Director (Anrey Zvyagintsev of Leviathan and The Return), is the way it tells the story of an everyday, normal young man recently graduated and taking an interim over the summer so that he can figure out what he wants to do with his life. This is contrasted with the older man who is his boss, offering us these two perspectives on life in Russia. It’s a really interesting character study that brings in certain cultural assumptions in order to tell its story from the perspective of these young ambitions and this world weariness.

Iceland

Woman at War

Heartstone

Juniper Tree

In the Spotlight: Metalhead

Not unlike the other European countrires that surround it, Iceland is a study of the ways in which certain levels of isolation, homogenuity, and specific economic realities can shape a Country’s culture in very particular ways. When it comes to film, this becomes readily apparent in Iceland’s penchant for matter of factness when it comes to life and awareness of it. There’s an illustriousness to their films that comes from an industry that hasn’t faced a lot of struggle and change but that also remains modest and focused on life lived in their Country. This is paired with the darker edges of their locale, which can be both a point of mundaness and beauty. It is out of this that we get something like Metalhead, a film that finds something universal in the particular and seemingly very Iceleandic story of this young girl caught between two worlds, or two ideas of the world she occupies.

1. Mr. Jones

1. Mr. Jones

3. Miss Juneteenth

3. Miss Juneteenth

5. The Vast of Night

5. The Vast of Night 5. Residue

5. Residue 6. The Glorias

6. The Glorias 7. Radioactive

7. Radioactive 8. Broken Hearts Gallery

8. Broken Hearts Gallery 9. The Midnight Sky

9. The Midnight Sky

11. Troop Zero

11. Troop Zero 12. The Call

12. The Call

14. Blow The Man Down

14. Blow The Man Down 15. The Kid Detective

15. The Kid Detective

17. Burden

17. Burden 18. Selah and the Spades

18. Selah and the Spades

20. Judy and Punch

20. Judy and Punch

Even looking back over our 16 years of marriage, which has not been without its struggle, what I can see most clearly is all the ways decisions I have made led to failure, be it financial distress, shifts in career, or the outcome of my regular old bumbling nature. For me, Mary, or Jen, is my best quality.

Even looking back over our 16 years of marriage, which has not been without its struggle, what I can see most clearly is all the ways decisions I have made led to failure, be it financial distress, shifts in career, or the outcome of my regular old bumbling nature. For me, Mary, or Jen, is my best quality.

The Phantom Carriage (1921)

The Phantom Carriage (1921)

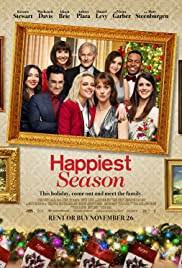

Happiest Season/Fatman (2020)Figured I would highlight two of the better seasonal watches to come out in 2020, even though they could not be further apart. Happiest Season is perhaps a bit conventional, but the charisma of its leads (Levy is so good), the wit of the script, and a really well crafted relational drama that follows two young woman as they navigate Christmas with a family that does not know they are together or that their daughter is gay elevate this as a very worthwhile Christmas viewing. It’s very funny, quite moving at points, and chalk full of all the stuff you might want from a good, sweet holiday film.

Happiest Season/Fatman (2020)Figured I would highlight two of the better seasonal watches to come out in 2020, even though they could not be further apart. Happiest Season is perhaps a bit conventional, but the charisma of its leads (Levy is so good), the wit of the script, and a really well crafted relational drama that follows two young woman as they navigate Christmas with a family that does not know they are together or that their daughter is gay elevate this as a very worthwhile Christmas viewing. It’s very funny, quite moving at points, and chalk full of all the stuff you might want from a good, sweet holiday film.