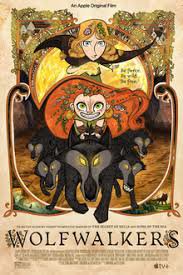

It should not be suprising I suppose that one of my favorite films of the year (spoiler alert) came from the small, Irish, animation studio (Cartoon Saloon) that gave us the likes of The Breadwalker, Song of the Sea and The Book of Kells. This long awaited 2020 release arrived with much hope and anticipation and did not disappoint in its dazzling example of cinematic invention.

The studio’s films have long been interested in shedding light on the beauty of Irish mysticism and mythology, but unlike the afforementioned films (Song of the Sea and The Book of Kells), the Celtic Mysticism in this beautifully hand drawn 2D animated film sneaks up on the story. The quiet nature of the first half hour gives us the space to really get to know these characters, the village and community, while offering us glimpses of the forming culture that surrounds them, much of which lies invisible and forgotten by the village dwellers. We get the sense that their world is much bigger than what lies witin the shelter of the city wall, and this sets us up to desire the revealing of this mystery which lies just beyond in the thick of the surrounding forests, the same forests now envisioned as a roadblock to their wanted progress.

One of the thing Wolfwalkers does is bring together myth and history as a way of helping us to understand the larger story of the Irish people. With the inclusion of The Lord Protector as Oliver Cromwell, Wolfwalkers reimagines the conquest and Chrsitianizing of the Irish peoples in its historical and mythological context, with the wolves symbolizing the Irish heritage lost to this tragic story of theses abuses of power and progress. The mystery of the woods contains the myths of this heritage, something the people living within the walls of the city have been taught to now fear and oppress. From the perspective of the Lord Protector, the obstacle that stands in the way of progress is the forest, and what stands in the way of tearing down the forest are these mythological wolves and the wolfwakers thought to live among them in Irish lore.

What the film does so brilliantly is weave together this sense of history and myth as a way of locating this deep rooted Irish spirituality and coaxing it to the surface as liberating and opposing view to this kind of destructive power. Caught up in this reclamation of Irish cultural beauty are modern notes of feminism and racism as well, which intermixes seamlessly with the ancient perspective of its spiritual traditions. It’s a well crafted script that works in perfect tandem with the brilliant animation, which takes the nostalgia of that old hand drawn animation and creavitely imagines it as a fresh taspestry on which to explore new ideas and approaches. A memorable soundtrack and score also allows it to reach for moments of true tanscendence.

So imagine my surprise then when I encountered multiple podcasts talking about this film in a fashion that unabashedly, if unintentionally writes off this rich Irish spirituality as little more than an ancient lie. Reclaiming this Irish heritage for these think pieces essentially means learning how to see these old belief systems as one and the same- outdated modes of thinking that have been superseded by modern science and thus can be enjoyed today as “fairy tales” (to borrow the most oft phrase I heard) rewritten from a modern and very Western enlightenment lens.

What’s ironic about these interpretations of the film is that the very image they are condemning (Christian conquest and assimilation) becomes the fuel for their own analysis of the story. For these critics and podcasters, there is no distinction between myths, fairy tale, Irish spirituality or Christian history. They are simply all to seen in t he same light as falsehoods, dangerous superstitions better relegated to categories of our “rationalized” imaginations.

Which to me is a very narrow understanding of what these ancient stories are. Equally a very narrow understanding of the ways in which myth, legend, history, folklore, and even its more modern iteration “fairy tale” work in relationship to one another.

Perhaps more so yet, it suggests a lack of awareness of the beauty of story and storytelling, or at least of what makes something like Wolfwalkers beautiful as a rich expression of a long and colorful Irish heritage. In a very real way, these criticts and podcasters and writers are actually commiting the same sin that the colonizers did so long ago. They are assimilating Irish spiritualism into their own, largely Western perception of enlightenment ideals, telling it what it should and must be in order to be valued and taken seriously. The problem is, once you diminish this story to these calculated and heavily guarded definitions of “fairy tale” as falsehood. you have lost the source of its beauty and your ability to see images like wolves not simply as a cold and empty metaphor, but as a living breathing picture of the cultural spirit that informs it and gives it life.

I found myself in a similar conversation recently regarding how to understand the story of Christ’s birth, with people who casually toss it aside as “just a myth”. They used this word in a highly dissmissive and condescending fashion, suggesting that one could not appropriately understand the story of Christ’s birth without carefully categorizing it as a lie and a product of old superstitions. What happens then is an often misunderstood temptation for many to want to condemn the Christianizing of the pagan stories that they see informing it. And in doing so they likewise, if inadvertently, force these pagan stories to submit to the same “modernized” rules of how story must work.

Once again, this all falls under the same category of falsehood and calculated imagination, stripping the stories of the source of their power and diminishing their ability to speak as “spirit” filled stories in the ancient perspective. This limits our ability to be formed by their truth, taking spiritual truths and rewriting them as simple, moral lessons, even though these stories have a much broader point of perspective in mind.

I was having a terrible time of trying to to get this point across when, purely at random, I came across this wonderful new podcast called In A Certain Kingdom, cited as a “Retelling of Slavic Fairytales and Myths, and an Explanation of How These Stories Help Us Better See and Live in the Real World”. It is a podcast born out of the Eastern Orthodox Church, a culture and faith expression that looks and feels much different than our Western expressions of faith, with Orthodoxy retaining much of the wonder and magic of that ancient context and form of of storytelling. In this tradition, myth is not seen as the enemy of truth, rather it is the doorway to truth, the bringing together of revelation and history, of inquiry and imparted knowledge.

The first episode of the podcast looks at the old Russian fairytale “The Tale of Prince Ivan and the Grey Wolf”, retelling the story and then taking some time to intelligently reflect on its significance for us as modern readers. As a story full of ancient symbols and ideas, from firebirds, trees and water to ideas of life emerging from death and of hidden spiritual knowledge being revealed through our awareness of the other, it provides an amazing lens through which to approach both this ancient story and ancient world that we find in Wolfwalkers and the Christmas story. It raises the beauty of an ancient cultural perspective perhaps long lost to our modern biases to the surface, daring to imagine what it is to find wonder in transcendent notions such as God, creation, spirit and beauty.

To this end, there is a transcript that goes along with the first espisode of In a Certain Kingdom that I thought provided some really powerful words regarding our relationship to story and our ability to truly encounter someting like the Christmas story with a true openness to its ancient perspecive. I will link here to the full episode should you rather find the time to listen to the whole episode as you prepare for the culmination of the advent season (or as someone who doesn’t celebrate Christmas in the Christian sense), but the part that I quote below I found especially compelling as I think about the relationship between faith, memory and and story, something that I think is equally true for any faith tradition, regardless of whether you celebrate Christmas or not. In truth, in a society like my own that has its own unfortunate history of Christian led abuses and historical tragedies, Christmas as a largely embraced and secularized holiday can feel oppressive to many simply because of what it represents (tragedy). As Wolfwalkers reminded me of though, the answer is not to simply conform these ancient cultures and belief systems to some kind of idealized and monolithic modern, Western narrative in response. To do so would be to commmit the same tragedy, just in a more ideological form. Perhaps the answer is to actually come to these stories with humility, inviting them to reveal something to us that we need to hear, to be open to the spirits forming work in and through their cherished and long held narratives.

Link to the full podcast episode: https://www.ancientfaith.com/podcasts/certainkingdom/prince_ivan_and_the_grey_wolf

(EXCERPT FROM THE TRANSCRIPT FOR THE PODCAST “IN A CERTAIN KINGDOM”, EPISODE 1, The Tale of Prince Ivan and the Grey Wolf)

Whatever shadow may fall on your life—maybe you’re worried about the fate of your country, or perhaps dark thoughts visit you concerning your own future, or maybe your entire life seems an unbearable wound—remember the fairy tale. Listen to her quiet, ancient, wise voice.

These perhaps surprising words were spoken by a Russian philosopher named Ivan Ilyin, speaking to an audience of Russians in Germany in 1934. Strange, it sounds a lot like something you might hear now in our pandemic-ridden country. His world had fallen apart already. His country had been overwhelmed by Communists, and he was just about to witness the worst slaughter ever inflicted by man upon fellow man. And yet, where did he find his consolation? In the simple, some would say childish, fairy tale. He says:

Don’t think the fairy tale is a childish diversion, not worthy of the attention of a grown man. And don’t think that adults are smart and children are stupid. Don’t imagine that an adult has to stupefy himself to tell a story to a child. No (he continues), is it not perhaps the opposite? Aren’t our minds the source of most of our woes? And what is stupidity, anyway? Is all stupidity dangerous or shameful, or is there perhaps a kind of intelligent stupidity? Or better yet, let’s call it simplicity, something desirable and blessed, that begins in stupidity but ends in wisdom.

Socrates famously said, “All I know is that I know nothing.” And yet, even now so many of us are convinced, whether we realize it or not, that our own minds can contain the universe, that science can help us understand the mysteries of life, that a thorough training of our minds can make us masters of our own existence. Well, that hasn’t been happening these past few months as the pandemic rages, and it seems to me that the more people read and the more science they seem to have on their side, the less they seem to understand what is actually happening. And yet the more we feed our minds, the less we think about our hearts. That’s the point. And the results are not good. Many of us have lost the ability to see the beautiful in the world completely, not only because of the pandemic—even before. Many of us were stuck in our own chosen ideologies, points of view. And how often have you seen people on social media or in person battering down those who disagree with them into submission to their own will? And it’s true, our world is no longer as enchanted as it was when we were children; the magic is simply gone. Have you noticed that for many of us, so has the joy? Well, Ilyin has something to say about that, too; here’s what he says:

Only he who worships at the altar of facts and has lost the ability to contemplate a state of being ignores fairy tales. Only he who wants to see with his physical eyes alone, plucking out his spiritual eyes in the process, considers the fairy tale to be dead. Fine, let’s call the fairy tale simplistic, but it is at least modest in its simplicity. And for its modesty, we forgive it its stupidity. After all, it takes courage to be simple. The fairy tale doesn’t even try to hide its inaccuracies. It’s not ashamed of its simplicity. It’s not afraid of strict questions or mocking smiles.

Ilyin continues; he says:

Fairy tales are not fabrications or tall tales, but they are poetic illumination, essential reality, maybe even the beginning of all philosophy (and, who knows, possibly even theology). Fairy tales won’t become obsolete if we lose the wisdom to live by them, no. We have perverted our emotional and spiritual culture, and we will dissipate and die off if we lose access to these tales.

I’m talking not about physical death, but about something much worse; I’m talking about spiritual death.

What is this access to fairy tales? (continues Ilyin). What must we do to make the fairy tale like the house on chicken feet, turn its back to the forest and face us? How can we see it and live by it? How can we illuminate its prophetic death and make clear its true spiritual meaning?

But, really, Ivan Ilyin, are you serious? Spiritual meaning? Talking wolves, houses on chicken feet, and wimpy princes crying on tree stumps? What are you talking about? Well, Ilyin’s talking about an entirely different way of relating to the world. Here’s what he says; he says:

For this, we must not cling to the sober mind of the daylight consciousness with all its observations, its generalizations, its laws of nature. The fairy tale sees something other than this daylight consciousness; it sees other things in other ways. You see, the story itself is art. It conceals and reveals in its words an entire world of images, and these images symbolize profound spiritual states.

Spiritual realities transcend what we can see or express in words, and yet we know they exist. We know it in the relics that we see, in the myrrh-streaming icons we smell, and in the lives of men who transform everyone around them from beast to angel. I’m talking about the saints. These realities, before we can grow up spiritually to experience them for ourselves, they’re often best expressed in metaphors, in images, or in symbols—in other words, in stories. It’s a kind of art similar to myths and songs. Here’s what Ivan Ilyin says; he says:

It comes from the same places as dreams, premonitions, and prophecies. This is why the birth of a story is at the same time artistic and magical. It not only tells a story, but it sings it into being. And the more a fairy tale sings, the easier it enters into the soul, and the stronger is its magical force: to calm, to order, and then to illumine the soul. The fairy tale comes from the same sources as the songs of mages with their commanding power. This is why stories repeat phrases and images so often.

After all, think about it: Christ himself, reaching down to the low level of his fallen creation, told the most compelling truths in the most compelling way: through parables and through symbols. Here’s another quote for you. This is J.R.R. Tolkien, from Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics. He says:

The significance of a myth is not easily to be pinned down on paper by analytical reasoning. Its defender is thus at a disadvantage. Unless he is careful and speaks in parables, he will kill what he is studying by vivisection, and he will be left with the formal or mechanical allegory, and what is more, probably with one that will not work. For a myth is alive at once and in all its parts, and it dies before it can be dissected.

Interesting take on the movie!

LikeLike

Thanks for reading 🙂

I had been wrestling with these thoughts ever since seeing the film and reading/listening to some reviews. And then I got into a discussion elsewhere about christmas, and it struck me that the discussions felt very, very similar.

And then I came across the podcast and it helped put some of those thoughts in perspective..

LikeLiked by 1 person