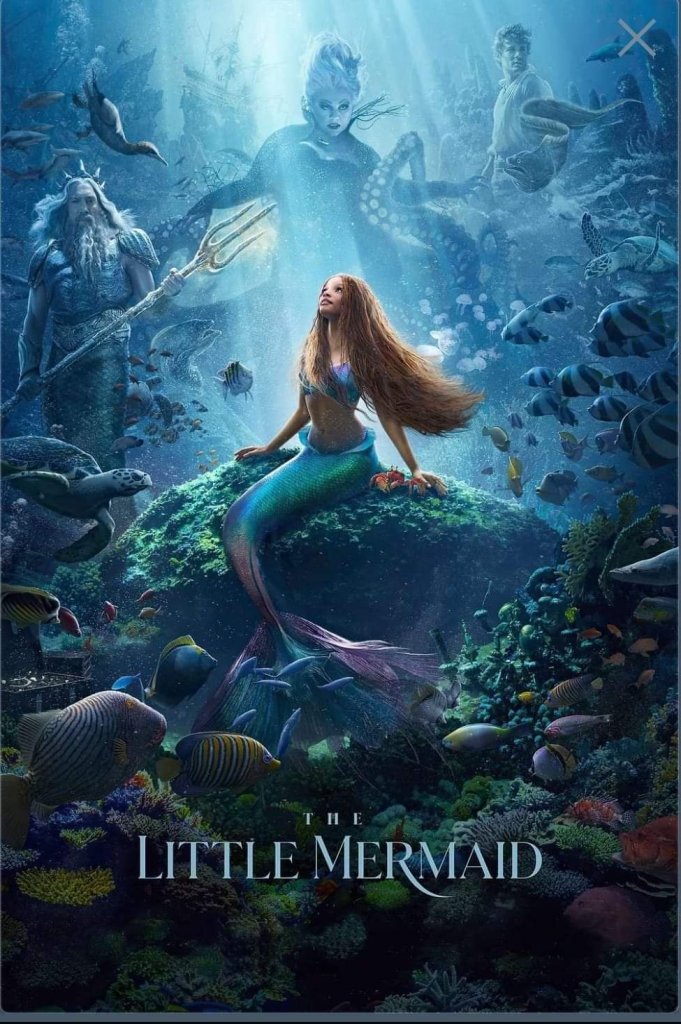

Film Journal 2023: The Little Mermaid

Directed by Rob Marshall

There is a lot to love and much to appreciate in a film that exhibits a few minor issues when it comes to “translation”.

Live action remakes tend to demand particular attention to what they want to emphasize and what gets reimagined so to speak within a different mode of filmmaking. Where The Little Mermaid is able to use the live action to its advantage is in accentuating the different settings. With the whole motif of worlds colliding-worlds reconciling, be it sea and land or parent and child, the film utilizes different aesthetics as a way of emphasizing the otherworldly vibrancy of the world under the sea and the old world romanticism of the seaside village on land.

Further yet, the filmmakers flesh out a clear thematic focus using contrasts, like the diversity of the mermaid daughters meeting with the diversity of the lands cultural expression. Or the mirrored stories of daughter and son being confined on land and sea. Of course the familiar beats of the story use the larger backdrop of stigmatization towards land and sea creatures as a means of bringing these worlds together, but there is a certain intimacy this remake affords the characters themselves in terms of the subtext of their own journies being given clarity and voice.

Where the film shines the most actually is where it spends a good deal of time on the land, telling what feels like a good, old fashioned medieval love story. Here the humor and the set pieces and the plot are all working in perfect cohesion, providing a really satisfying arc to follow from sea to land and back again. As I mentioned, it is soaked in old world charm, and this whole middle section I found to be particularly riveting.

This is purely my opinion, and others might have a different experience to this end, but the weakest part of the film “in translation” is the third act climatic moments. This isn’t all that surprising given that this is where the CGi is demanded the most, and where the source material is least suited to the live action approach..I would also add my other critique here, which is that too much of the film is cloaked in darkness. There are moments when it works (a moonlight boat ride for example), but there are also moments where it becomes difficult to make out the details. That’s a small note though in a film also filled with wonderful and striking visual sequences.

To add to the above, I would also suggest that I feel Melissa McCarthy was slightly miscast as Ursula. She has moments where it is clicking, but the third act problem could have benefited from a more grounded persona. Her tendency to play over the top makes the character slightly campy when it felt to me like it should have veered darker and more serious. An opportunity to give Ursula that real world human presence. Bardem gets closer on this front.

Overall though I do think this film proves to be a resounding success, and if I had to hang that one single dynamic I would single out Halle Bailey. This is a true star in the making moment, and she deserves all the accolades that should be going her way. Closely tied to that is the chemistry between her and Jonah Hauer-King, who plays Eric. Pitch perfect and resounding with heart. In fact, the whole film is resounding with heart. Say whatever you will about the remake, it feels authentic and true and even timely and important. And that goes a long way in making a case for its existence. I think Beauty and the Beast more effectively managed all three acts on a visual level, striking a more consistent tone, but the moments where this one clicks, it really shines.