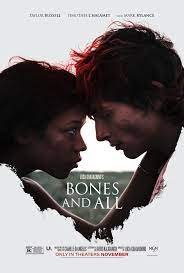

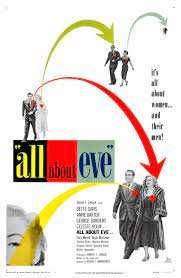

All About Eve (Directed By Jospeh L Mankiewicz)

An outstanding character study built on the stand out and largely complimentary performances of Bette Davis and Anne Baxter in the role of these two women in quiet contest each with their own interests and motivations. The script is equally wonderful as it weaves in some wonderful twists and turns. And that ending. Absolutely transfixing and haunting.

Definitely shines as a true classic with some wonderful reflections on the artistic world, the creative process, and its ambitions and allure.

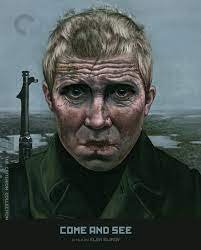

Come and See (Directed By Elem Klimov)

It’s not often an initial viewing inspires a five star rating. Typically my rule is time and consecutive watches for bumping it up from a 4.5. Every once in a while a film comes around that is simply that undeniable. This is one of those.

A true masterpiece in every way, so much so that it’s nearly impossible to say anything profoundly observant that would add to this experience in any way. Certainly nothing that hasn’t already been expressed many times over through the years since it’s release. I’m content to say this is simply a film you need to experience in order to fully appreciate, an inspired story of two young lost souls caught up in the unimaginable horrors of war being forced, well beyond their years, to wrestle with the tension that exists between hope and despair.

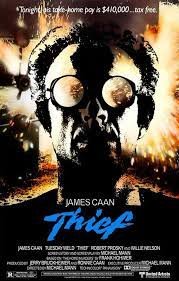

Thief (Directed By Micheal Mann)

Mann’ debut feature, and he directs this like he is already a master of the craft. Captures the grime and the grit of its street level story, a setting which also allows the characters to follow suit (also an early feature for James Caan). A deliciously fun ride that manages to expose the fallacy of the great American dream.

High and Low (Directed By Akira Kurosawa)

A superbly written detective story that simply moves with the dance of its effortlessly positioned performances. The first hour alone features some expectionally written dialogue stationed as it is in a singular apartment. The high and low of the story frames the films setting as it moves through the city with the second half broadening our point of perspective with the unfolding mystery.

Everything about this, from the small details of the story and the set pieces to the cinematography is richly designed and an example of genuine craft that demands your attention and likely several rewatches. Simply brilliant.

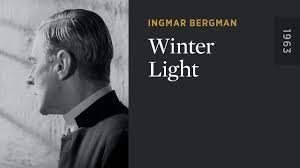

Winter Light (Directed By Ingmar Bergman)

“If only we could feel safe and dare show each other tenderness. If only we had some truth to believe in. If only we could believe.”

I’m not sure I can recall a more honest prayer being uttered. That it emerges from such a striking posture of doubt and struggle is what makes it more than merely honest, but also palpable and formative. Building off questions raised in Bergmans previous film regarding the tension that exists between God’s love and Gods seeming silence in the face of tragedy, Winters Light digs deep into the feelings of despair that emerge when the silence appears to be far more present than the love.

The question of Gods love is intimately attached to loves expressive voice in relationship to one another, suggesting that wrestling with God is not something we do in isolation. It is community with one another that holds the power to awaken is to communnion with God as the same tension plays out in the inner workings of our lives. We see this in the contrasting responses of the Priest’s joyous celebration over the liberating acceptance of unblief and the parishioners concession of lifes futility. This is a tension that longs to be reconciled as we are confronted with the cruel nature of this world. The tension becomes more real when we bear the weight and responsibilty of stepping into the struggle of another to offer hope.

There is a thread of personal failure that makes its way through the character arc of the Priests journey. He fails himslef, his marriage, his mistress, his parishioners, his church, and ultimately God. There is a sense in which this becomes a necessary beginning point for contemplating the nature of God, beckoning us towards an acknowleegment that we are not in control and that we desperately long for something to make sense of our uncertainty. In the above prayer this doesn’t come through certain answers but rather a posture of humility and acknowledgment of both our fears and our longings. As we see this transforming the way we see one another, we can see it transforming the way we see God, with love being the truth that once again makes itself known.

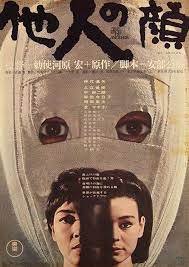

The Face of Another (Directed By Hiroshi Teshigahara)

“Looks like you’re getting used to the mask. Or is the mask getting used to you?”

The story follows two essential characters- a man with a facial disfigurement who gets a mask which he wears to cover up his blemishes, and a young woman with a scar that holds in its presence the larger story of war, post war reality, and socio-political headship. Here the intimacy of the indivual story is seen through the larger context of the world that forms it.

This comes alive through the Directors attention to detail, with each frame and each sequence calling us deeper into the the film’s questions. In many ways these questions revolve around identity and identity crisis, wondering about how it is that we make sense of who we are where we are in a given moment and a given context. Whats powerful about this is the way the camera awakens us to matters of perspective, the one that we perceive looking in on us and making judgments of us and the one we perceive and judge looking outwards. These perspectives are shaped togther informing one another as we attempt to move out into the world and participate as we are, or as the mask suggests, as we wish to be seen.

The uncertainty that comes with the fear of being recognized for who we are lingers in the forgotten spaces of the details, which makes so much of this film an exercise in memory. Memories of the forgotten past set in tension with the unseen future, an idea that this young woman with a scarred face projects on to the larger socio-political reality. This is, in its way, what pushes us in our insecurities to engage in a constant process of juggling several masks at the same time, with the question of how we begin to unconsciously conform to these identities being a crucial one. It’s relationship to the larger culture in terms of that inevitable tension between the ways we are formed by it and the ways we inform it is where we uncover the layers, ultimately allowing us to reapply this to the notion of the indivual in helpful ways.

A powerful film that will require mulitple watches to uncover the richness of its detail and it’s substance.

Cries and Whispers (Directed By Ingmar Bergman)

The cries and whispers of the inward soul spill out into the seemingly endless void of an ambivalent, uncaring universe. We do not matter because we do not matter to oursleves.

And yet, the mystery begins to speak quietly from void in ways unexpected- by way of someone who hears. Someone who picks up these cries and whispers and formulates it into a conversation. We matter, it turns out, because we matter to an other, and this frees us to matter to ourselves.

This is how the mystery makes itself known. Where God has heard the cries and the whispers he is given it to us to stand in the void as the hands and feet of the one who hears, the one who loves, the one who, in its most basic expression, is present. Simply togther.

The Death of Mr. Lazorescu (Directed By Cristi Puiu)

Operates as a scathing critique of the health care system whole affording its workers and the patients caught within it a great deal of empathy. It’s surprisingly funny too for something this serious and important. Paints a deeply human portrait.

Sweet Smell of Success (Directed By Alexander Mackendrick)

A breathtaking romp through the mud of some generally disgusting and nasty human behavior. This film is chock full of memorable and great lines, but one word rings true- they are all “snakes”. No other way to describe this mash up of characters.

The story essentially follows a columnist writing for the New York Times and his efforts to break up a romance he disapproves of between his sister and a jazz musician. He has a way with words of course and is used to being in a position of control. The more things spin wildly out of control the deeper he sinks into this increasingly self interested and merciless scheme. This is where charachter and motivations and the desperation of the damaged ego rises more and more to the surface.

The fllm translates readily across eras and feels uncomfortably familiar to certain traits of modern society. While the treatment of women on display rings loud as a product of its time (making its commentary that much more profound) what’s perhaps more scary are the ways this still expresses itself today in different forms.

The black and white sinks this all into the wonderful noirish vibes, making this a real visual delight along with a near perfect script and outstanding performances.

Fanny and Alexander (Directed By Ingmar Bergman)

From the opening scene Bergman beckons us forward into the world of this film and invites us to linger in the shadows where we are able to experience the story from the perspective of a child. Or perhaps more poignantly from the the perspective of widened adult eyes peering backwards into the solace of those complicated childhood memories. It would seem, given that this was his final film, and a majestic one at that, that Bergmans desire was to capture the trajectory of his career, writing this story through the lingering presence of his own formative experiences and shaping that against a career of deeply expressed longing, exploration, questioning and curiousity. Where the darker edges still seem to haunt him here spiritual imagination takes over bringing to life visions of a world that is able to move effortlessly between this earthly reality and transcendent truths. The film weaves together the supernatural and the natural tightly until they cannot exist above or apart. Similar with the fluidity of the life and the dream which Bergman Directs with expert attention to the cinematic transitions. Certain key images, the puppets being a highly visible one, anchor is in a sense of belonging functioning as both comfort and fear.

The films epic runtime takes its time and immerses us in its story, allowing us thd chsncd go get to know the characters before deconstructing their grace filled life with the intrusion of a legitimate horror, eventually putting it back together by way of this persistent grip on hope and innocence.

It’s a profound film built around a grand vision and told with an intimate and personal touch.