I’ve been working through a Torah course on the book of Judges as a follow up to the recent time I spent in the books of Numbers and Joshua. And while I have only recently started my journey through this tumoltuous time in Israel’s history, some of the context for the book that I have been uncovering has started an intriguing line of thought that I felt was worth pausing to briefly reflect on.

To Name A Judge

The English title for the book’s title comes from a word that translates similarly in the Greek, the Latin and even later English (to make it revelant to my personal, modern context). As with many words that translate from the original Hebrew, the word itself faced (and does face) some specific problems when it comes to capturing the essence of it’s original meaning. This might be most readily evident when we see the word in modern judicial terms, as is the tendeny in the English speaking West. The root of the term “judges” comes from the Hebrew word that evokes something broader than simply a judge offering up a verdict on someone who is either evil or who committed an evil act (and the flipside the declaration of innocence). At its core, in Hebrew the term “judges” conjures up allusions to one who both saves and one who reforms. It is a relational term that evokes images of a savior rather than demonstrating a legal or legislative postion, and images of purifying or reforming rather than a condemning sentence.

The root of the word flows from Moses story in Deuteronomy (chapters 16-18), where we see “judges” defined as appointed figures alongside the Priests (Deut. 16:19-20; 17:8-13), a concept which has to do or is concerened with living as the people of God and in relationship to God and one another. At this point in Israel’s story we see the establishment of this new community, a people called to demonstrate God’s vision for the world, taking shape.

What is important to remember about the term “judges” is that this same appointed position flows outwards into the concepts of Priest, Prophets and the Kings. All of these are terms that relate to a kind of appointed position or governance, and the best way to understnad Israel at the time that these terms emerge is as a decentralized group of disparate people coming together from different cultures and different walks of life to co-exist with a shared experience of oppression. During their time in Egypt, and subsequently throughout the experiences that follow the Exodus story, this would have been a growing mix of all kind of people who simpy shared in their experience of being under the Egyptian power (according to the Hebrew Tradition). Similar to the surrounding nations, and further on in Greek society, one could then describe Israel as a loose confederation of disparate states held together by single collective force. In the ancient world this was most often religion, which itself was bound together through a nations or a people’s origins story. These origins stories were both how a nation distinguished itself from another and how they co-existed as a diverse people with a unified vision.

What is interesting then is to track what happens to these different “nations” or people groups as one or another of them begin to develop into empires. In most cases what woud would happen is the empire would recognize that the best way for these conquered nations to live together under the rule of a single entity was to be afforded some degree of freedom to coexist within their belief systems, so long as allegiance was payed to the ruling empire and religious system through trade and money. In other words, in a world where mutliple origin stories had to be synchornized in order to function productively in service to a powerful empire’s rule, religion was often traded for some version of forced economic and trade relations. Which is not to say that religion was done away with, but simply that they allowed religious observance through (expected and forced) economic participation. This is what it meant later on in Jesus’ day to say that Caesar is Lord under Rome. This is the very nature of assimilation.

And when a nation is forced to assimilate, what often happened is that people would begin to forget about their origins story and find greater comfort and safety through marrying their own tradition to the customs of the land they now reside in. This was the state of Israel at the time of the Judges. The time of the Judges (traditionally there are 12 of them) reflected the official shift from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age, which coincided with the development of the “sea people” (the Philistines) and, theologically speaking, provides the bridge between the end of Joshua’s story and the beginning of the era of the Kings. In tension was their memory of their origins story, which at this time was the story of the Exodus which culminated with Moses on the mountain, which later melds with the Genesis narrative of creation and Abraham,

In both Moses’ narrative and Joshua’s narrative we essentially end with a call to Covenant renewal. The reeestablishing of their collective religious memory as a unifying force. Between Joshua’s death and the period of Judges we see an immediate decline in the state of the people. We encounter an almost anarchist tone of a people too numerous to count in the book of Numbers, albeit a tempered one, where this eclectic and diverse group of people living in the land together have quickly forgotten the Exodus story (in the same way they did in the book of Numbers… AND THEY JUST LEFT EGYPT!!). They lived essentially without a ruler, rather appointed persons and offices, that is until they started to see the powerful nations around them (in the book of Judges we see the Philistines), nations who had rulers.

Prophet, Priest, Judge and King

To repeat again, the notion of a “judge” belongs in the same designation as prophet, priest, and king. And all of these titles, although expressed and defined differentlly throughout the different situations that these appointed figures encounter, have two essential descriptives in common-

1. They are appointed by God

2. They are intended to deliver or to save

As well, they are best understood in terms of a method of governance. A way of unifying a diverse group of people within a single vision of where they came from and where they are headed. Of concern in the midst of this, and what the Israelite story could speak speak to, is this figuring out of the relationship between their cirucmstnace and their own actions. They are freed from Egypt, and yet freedom often leads back into further slavery to surrounding nations as we follow the Israelite story. We see this in the desert, in the occupying of the promised land, in the exile and demolishing of the temple. Thus what came to be undertood is that if a promise of freedom is defined as a covenant, either God has broken His side of the promise or they broke theirs. In an effort to locate the reason for their continued oppression, their point of perspective continues to flow back and forth between these two realities, with appointed positions raised up to remind them of God’s faithfulness and their sinfulness as the root of the issue. If they find themselves in positions of suffering and far from the freedom they hope for, it is not because God has abandoned them, but rather because they have chosesn something different than God’s vision for their people. As a temple text established to hold this in plain view, this then forms the crux of the Genesis narrative, a narrative that imagines the same dueling force of blessings and curses that flows from the mountain on which Moses first establishes this marriage between Yahweh and Israel as a functioning and brithing community.

In the scope of the larger Christian narrative, where we see this story finding its climax is in the person of Jesus. As Jesus arrives on the scene, he arrives in line with these designations of rule or governance that have run through Israel’s history. He embodies the completeness of these designations, designations that are constructed according to the rule of the surrounding nations, such as the call for a King if simply because the powerful nations that surround them have a Kingd. These appointed positions can be seen as broken signposts, to borrow the language of N.T. Wright, of something greater, flawed characters calling a flawed people to unity in the midst of division as they await the promise of the fulfilled covenant. Jesus embodies the people’s collective memory and becomes that unifying force. All things now come together in Jesus who is seen as the restored Temple, the New Adam, the full Israel, the indwelling or tabernacling of the presence of God in the lives of a people who are declared loved by God.

It is in Jesus then that this particular label of “judge” finds its clearest expression as an intimately formed Jewish idea. As the story of Israel has been unfolding, the trajectory begins with one man (Adam, the image of God), moves outward from the garden (which represented God’s unified vision for the cosmos, for the world, the divine throne room where he occupies the heavens with the earth as his footstool) to the story of Noah (which in this progression provides the central antithesis to this unified vision now reconfigured through the violence of Cain and Abel that breaks it apart). Here we see a society built on the shedding of blood being held in contrast with the unity of the garden, with the flood story functioning as a de-creation narrative in patterned allignement with the Genesis origins story of the waters held above now being let go. This returns us to the garden through this vision of these symbolic “pairs”, which gives us a picture of this return to vision of unity within our diversity that through the covenant with Noah moves forward through one man (Abraham) with a renewed vision for how this unity can and will work- one man for the nations (the world). This is what Abrahams name literally means. Thus we find the unfolding narrative that becomes the essence of the Christological or messianic expectation. This one man (Abraham) becomes embodied in a single nation raised up for the sake of th world, through which we then begin to narrow in scope again to a family (Davidic line) followed by an even further narrowing to a single seed. Out of which we move into the period of exile and towards the fulfillment of the promise in one man, the New Adam (Jesus).

A couple important points here. Through this lens we can locate both the coming exile and the broken signpost of these failed titles of prophet, judge, priest and king to bring Israel to covenant fulfillment, as a de-creation process. A saving work. A purifying work. Similarly, we can see the state of Israel in the story of the “judges” in this way as well. Secondly, what we can recognize is the intention in seeing in the final judge (Samson, as is the case with King David and Moses and Joseph leading up to the Exodus) a Christ type. Consider that he is a Nazirite born with a declarative promise given from an exceptional birth, and that he is seen to be set apart for the sake of his people and sacrifices himself for his people in a kind of cleansing or destroying act with the purpose of fulfilling a decreation-recreation process.

The Uniquely Unifying Vision of the Israelite Promise

With this in mind, what is important to keep in mind when reading the Book of Judges is how this trajectory, this messianic focus and typology, and in Christendom this understanding of the fulfillment of these governing titles in Jesus, there is a single idea that seemed to set Israel apart from the surrounding nations. And it has to do with how we move from a unified people under God (or in the broader sense, religion) to a people for the world without getting caught in the trappings of empire. If the Christian narrative can be summed up as a singular contest, it would be as a contest of empires. There seems to be this ongoing tension presented throughout the Judeo-Christian story that suggests there are two ways of building society, beginning with the Garden as a constrating picture of a “building” society (one birthed in the tree of life, the other birthed in the blood soaked story of Cain and Abel), and then carrying through the story of a people set apart for a different vision of empire, perhaps most recognizably patterned against the story of Babel (a people unified under conquest and conformity and assimilation that becomes the literal and metaphorical template for “Babylon” that runs through Genesis to Revelation… the contrasting picture of empire). The problem that we find over and over again is that as nations develop into empires, a people (Israel) set apart to represent a contrasting vision of empire find themselves under conquest and thus desiring and conforming to the wrong idea of empire. Thus, as the messianic promise unfolds the office of prophet, priest, kind and judge continues to call them away from these visions of conquest and economic control and back to remembrance of their origins story. This most often happens through an ongoing cycle of deconstruction and reconsruction narratives, and perhaps more readily happens through thet flawed systems that see Israel mired in these undesirable cycles of violence and conquest as well. This is where Jesus becomes the fulfillment and fullest expressions of these office’s true concern- liberation and reform for the sake of a new creation. In Jesus we can see how Yahweh’s desire for Israel was something other than these destructive cycles which are not brought on by God’s doing, but rather by Israel’s forgetting of their true identity- where they came from and where they are headed as a people for the world.

What we actually find then is a nation, a people unified by their origins story for the purpose of then being pushed back out into the diversity of the world with a single vision of God’s love. By enveloping the diversity of the world into this unifying force that declares the power to uphold it, they can then bear witness to the new creation reality, a Kingdom being built according to a different way than economic purposes. In the story of the Judges this is demonstrated through being reminded of their covenant with Yahweh. In the Christian story this covenant promise is then fulfilled in Jesus. Scholarship pretty widely recognizes that this represented a unique vision in a world full of religious diversity. Rather than measure their Kingdom according to a self serving and self protected religious devotion on one end, or simply forgetting that religious devotion in favor of building their kingdom through the marks of conquest, economy and trade, on the other end, Israel was called to a different way of moving into the world- a people called to the kind of power that flows through the sacrificial image of the Cross. A people who become the least in order to bear witness to the true liberation being extended to all the nations of the world, a vision of liberation which represents Yahweh’s heart for a diverse world born through this being fruitful and multiplying purpose, and which carries the good news of a truly unifying picture of love embodied through its diversity.

Understanding Judges Through the Genesis of This Diversity

A recent and very wonderful episode of the Bible Project does an excellent job at breaking down how this picture is represented straight from the beginning in the Genesis text. Rather than the typical reading of Genesis that simply sees the man created to rule over his wife, and the rest being subservient to the original Adam as a form of understanding the true rule of God, a reading that has more in common with the opposing view of empire, we must begin with the Adam as representing a singular humanity. They note that this humanity is set alongside the idea of a diversity of animals, something that comes up again in the story of Noah in the notion of “pairs”. If Adam (humanity) is seen as the image of God, what we find in the creation story is a model through which to understand this concept of being unified in our diversity. The proper terms for Adam and Even, or hu-man and wo-man carried a strong poetic presence. It’s the idea of hu-man being divided in two so as to have a mirror image of ones self, the same identity as the image of God. Seeing a singular vision of God in the other as the image bearers of His identity and character. And it is in this mirror image that we then see the pattern of the Godly image for creation playing out, along with the ways in which our distorting of this image in the other leads to division. One divided then becomes one through the metaphor of marriage, out of which a singular whole is once again produced. This singuar whole then separates from the one (leaves mother and father) and goes through the same process, embodying the call to be fruitful and multiply.

What’s important to remember here is that this is not dogma but rather imagery, metaphor. If Genesis reflects an origins story, that means it is a temple text. And the tempe in Israel represents this unifying vision for creation with God as its indwelling centre, dwelling in their midst. The whole image of two divided and becoming one and thus creating diversity through this multiplying act is held together by this singular truth- in Yahweh and in Christ we find our unbroken identity that allows our diversity to flourish. It is when we we neglect this diversity for the sake of ourselves or oppress this diversity for the sake of our conquests that the covenant promise for this Edenic vision to be made new becomes broken and compromised. Which is why Jesus as fulfillment becomes such a hopeful and unique idea. When we are unable to see the image of God in what is essentially our mirror image (the other), then we tend to do harmful things to the other and thus ourselves. This is where Jesus becomes the image of God made incarnate (made in the image) and, through His death and and resurrection, indwells as the image of God in the hearts of all. Jesus calls us to see the other anew.

It’s also important to recognize that, as a metaphor, this idea of unity through diversity is blown wide open through the unfolding narrative of adoption that encompasses the story of Israel and the early church. Family, to borrow the ancient language, comes in many ways. Becoming one happens in many ways. Not simply through marriage or blood. The mirror image is simply the “other”, and in coming together in relationship to the other we are able to see the image of God and bear witness to its diverse presence as a single, declarative truth. This is what built the nation of Israel, is the bringing in of a diverse group of people from all different nations and with different gods by binding them together through a shared experience of oppression and liberation and then calling them outwards towards a different way of being together, one not built on the empires of conquest but the Kingdom of God. A people for the word.

This forms the meaning of John 12:47, where it says, “I do not judge anyone who hears my words and does not keep them, for I came not to judge the world, but to save the world“, and John 3:17 where it says, “do not judge anyone who hears my words and does not keep them, for I came not to judge the world, but to save the world.” To understand the appointed title “judge” in this particular OT book we must see it through this larger vision and context of Israel’s purpose, and the best way to do that is to to return to that origins story, the story that provides the context for continued covenant renewal. And then ask the question, how do we then grow as people of the covenant in our diversity without retreating into division. In truth, if Judges has suggeststed anything to me this early in the the Torah Course, it is that my own creation, de-creation process, which is what we find in judges, is a way towards that end. A recreation process.

According to film historian Daw-Ming Lee, one of the major gaps in scholarship surrounding the study of Taiwan film history is the period before the 50’s.

According to film historian Daw-Ming Lee, one of the major gaps in scholarship surrounding the study of Taiwan film history is the period before the 50’s. To truly understand Taiwanese New Cinema (New Wave), one needs to be able to understand their colonial past, as their more recent struggles to define themselves over (and depending on the lens one uses, against) mainland China has tried to locate their identity within and in relationship to this developing history. Taiwanese cinema was the earliest of Japan’s colonial industries (film markets), and can also be considered its most vibrant, which allowed the Taiwanese people to use this fact to quietly grow their culture even in in the midst of colonization.

To truly understand Taiwanese New Cinema (New Wave), one needs to be able to understand their colonial past, as their more recent struggles to define themselves over (and depending on the lens one uses, against) mainland China has tried to locate their identity within and in relationship to this developing history. Taiwanese cinema was the earliest of Japan’s colonial industries (film markets), and can also be considered its most vibrant, which allowed the Taiwanese people to use this fact to quietly grow their culture even in in the midst of colonization. THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT

THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT THE POWER OF LANGUAGE AND THE RELEVANCE OF ART

THE POWER OF LANGUAGE AND THE RELEVANCE OF ART A PRESENT AND FUTURE INDUSTRY

A PRESENT AND FUTURE INDUSTRY Where ever you start in exploring the Country through film, and it is likely you will begin to explore Taiwan through its New Wave films (which in and of themselves reflect a diversity within their shared focus and characteristics), what is immediately evident is the level of awareness and intelligence present in these films. As a cultured representation of a people defined by persistence, patience and awareness, these films refuse to rush their narratives. They hold a real ability to reflect, but with a past-present-future focus. And above all, they show a spirited refusal to give in to outside pressure, to conform, creating some of the most honest and integral artistic films available. A true inspiration, and an industry that will be exciting to watch develop even further.

Where ever you start in exploring the Country through film, and it is likely you will begin to explore Taiwan through its New Wave films (which in and of themselves reflect a diversity within their shared focus and characteristics), what is immediately evident is the level of awareness and intelligence present in these films. As a cultured representation of a people defined by persistence, patience and awareness, these films refuse to rush their narratives. They hold a real ability to reflect, but with a past-present-future focus. And above all, they show a spirited refusal to give in to outside pressure, to conform, creating some of the most honest and integral artistic films available. A true inspiration, and an industry that will be exciting to watch develop even further. I first saw the film Tolkien, directed by Dome Karukoski, back when it released in theaters. Back when theaters were still open and when the world wasn’t being held captive by a virus as fierce as any dragon from Tolkien’s mythology. I remember actually showing up to the theater intent on doing a double feature (with Aretha Franklin’s concert film, Amazing Grace), but being so affected by this film that I refunded my ticket to the second showing, downloaded the soundtrack, and just went for a drive into what was one of the coldest nights of that winter.

I first saw the film Tolkien, directed by Dome Karukoski, back when it released in theaters. Back when theaters were still open and when the world wasn’t being held captive by a virus as fierce as any dragon from Tolkien’s mythology. I remember actually showing up to the theater intent on doing a double feature (with Aretha Franklin’s concert film, Amazing Grace), but being so affected by this film that I refunded my ticket to the second showing, downloaded the soundtrack, and just went for a drive into what was one of the coldest nights of that winter. What I noticed this time around when watching the film was this intentional and constant movement from light to dark, dark to light, both on a narrative and cinematic level, allowing this to weave the narrative of Tolkien’s particular journey into one that must make sense of these two extremes living together, ultimately learning to imagine the world through his mother’s eyes, through that twisting lantern which becomes the reigning visual as it forms the backdrop of the final scene in which we witness Tolkien finally picking up a pen to write the first words of The Hobbit story.

What I noticed this time around when watching the film was this intentional and constant movement from light to dark, dark to light, both on a narrative and cinematic level, allowing this to weave the narrative of Tolkien’s particular journey into one that must make sense of these two extremes living together, ultimately learning to imagine the world through his mother’s eyes, through that twisting lantern which becomes the reigning visual as it forms the backdrop of the final scene in which we witness Tolkien finally picking up a pen to write the first words of The Hobbit story. As these two meet, this young man and young woman from different walks of life but also with a shared understanding of poverty, the film shifts back to the darkness and we find Edith employing language in order to describe their environment and to imagine another world in the light of the kingdom motif, one where poverty is not a constraint, where the light shines brighter than the darkness. This imagining once again cuts us back to the war, which sets the stage for this developing friendship between the brotherhood of four as another light in the darkness, bringing with it this proclamation that to die is not within our control, but to live is. The brotherhood become the soldiers, using their stories, their art, as their weapon to fight for good. Here both the beauty and the horror come together in a single but complex frame, one that is willing to sit in the tension that this creates for Tolkien.

As these two meet, this young man and young woman from different walks of life but also with a shared understanding of poverty, the film shifts back to the darkness and we find Edith employing language in order to describe their environment and to imagine another world in the light of the kingdom motif, one where poverty is not a constraint, where the light shines brighter than the darkness. This imagining once again cuts us back to the war, which sets the stage for this developing friendship between the brotherhood of four as another light in the darkness, bringing with it this proclamation that to die is not within our control, but to live is. The brotherhood become the soldiers, using their stories, their art, as their weapon to fight for good. Here both the beauty and the horror come together in a single but complex frame, one that is willing to sit in the tension that this creates for Tolkien. It is this magic that brings in the other thoroughline in this narrative imagery, which is the people and forces that occupy his story. Here we see Tolkien talking about dragons much in the same way as the brotherhood was talking about hell, applying it as a slightly ambiguous fusion of both light and dark motifs. Later on in the film this causes Edith to wonder whether she is actually the dragon in this story as Tolkien quickly redirects her attempts to speak of a princess into the larger imagery that his word is now imagining in terms of their own relationship together. Tolkien takes the normal princess motif and turns it into something so much richer, which is where the girl as the dragon then merges with this image of the dragon cast against the war, once again returning us to the darkness on a cinematic level.

It is this magic that brings in the other thoroughline in this narrative imagery, which is the people and forces that occupy his story. Here we see Tolkien talking about dragons much in the same way as the brotherhood was talking about hell, applying it as a slightly ambiguous fusion of both light and dark motifs. Later on in the film this causes Edith to wonder whether she is actually the dragon in this story as Tolkien quickly redirects her attempts to speak of a princess into the larger imagery that his word is now imagining in terms of their own relationship together. Tolkien takes the normal princess motif and turns it into something so much richer, which is where the girl as the dragon then merges with this image of the dragon cast against the war, once again returning us to the darkness on a cinematic level. One of my favorite scenes in the film is when Tolkien takes Edith to the opera. Or attempts to. As Tolkien is trying to count out pennies and comes to realize he doesn’t have enough to pay for the only remaining seats (the more expensive ones), we see the both of them coming together around their shared reality of feeling like life and circumstance has them imprisoned, a prison they both want to escape from. This leads them to duck into a passageway underneath the auditorium in the hopes of finding a way to sneak in. With all the doors locked and once again feeling dejected and defeated, the music starts to play and the two of them suddenly come alive, acting out the play as if they are a part of the story, a story they are creating for themselves. The shot of the kiss is brilliantly captured, with the camera slowly panning out and moving backwards down the passageway, giving it the allusion of the path that Tolkien had described during their dinner together.

One of my favorite scenes in the film is when Tolkien takes Edith to the opera. Or attempts to. As Tolkien is trying to count out pennies and comes to realize he doesn’t have enough to pay for the only remaining seats (the more expensive ones), we see the both of them coming together around their shared reality of feeling like life and circumstance has them imprisoned, a prison they both want to escape from. This leads them to duck into a passageway underneath the auditorium in the hopes of finding a way to sneak in. With all the doors locked and once again feeling dejected and defeated, the music starts to play and the two of them suddenly come alive, acting out the play as if they are a part of the story, a story they are creating for themselves. The shot of the kiss is brilliantly captured, with the camera slowly panning out and moving backwards down the passageway, giving it the allusion of the path that Tolkien had described during their dinner together. This encounter with the professor gives Tolkien a way back into his story, this grand vision of Middle Earth that is unfolding in his context and with real meaning and attachment to his experience and his world and the persons that embody this world. But now the timeline of the film catches up with the war, being interrupted by its announcement. There is an amazingly captured scene here where, as the war is being announced and people are erupting in emotions, Tolkien keeps trying to tell his story, even as his words slowly fade amidst the greater reality.

This encounter with the professor gives Tolkien a way back into his story, this grand vision of Middle Earth that is unfolding in his context and with real meaning and attachment to his experience and his world and the persons that embody this world. But now the timeline of the film catches up with the war, being interrupted by its announcement. There is an amazingly captured scene here where, as the war is being announced and people are erupting in emotions, Tolkien keeps trying to tell his story, even as his words slowly fade amidst the greater reality. It is a reuniting with Edith and the renewed expression of their love that brings these two frames, of light and dark, love and loss, together. In love, they must once again depart as he goes off to fight the war on the battlefield. Two dragons, one back at home, one he is about to face out there. One forming his darkness, one confronting his darkness and bringing it out. This is then twinned again with his relationship with Geoffrey, a narrative line that carries him through the war through Geoffrey’s death and his reuniting with Edith. The section that holds these two narrative lines together is a scene that finds him running helplessly through the battlefield, looking for the brotherhood but only finding tragedy, death, loss and horror. The film’s shooting of this scene brilliantly allows the chaos to gradually fade away, giving us an image of the Cross framed against all of the death around him, and ultimately leading him into the silence of what remains, alone with the demons of his imagination and his experience. All except for a single white horse that dots the battlefield, which contrasts with a rising figure cloaked in black. This is described by Edith as trench fever, the images given to someone scarred by what he has seen on the battlefield.

It is a reuniting with Edith and the renewed expression of their love that brings these two frames, of light and dark, love and loss, together. In love, they must once again depart as he goes off to fight the war on the battlefield. Two dragons, one back at home, one he is about to face out there. One forming his darkness, one confronting his darkness and bringing it out. This is then twinned again with his relationship with Geoffrey, a narrative line that carries him through the war through Geoffrey’s death and his reuniting with Edith. The section that holds these two narrative lines together is a scene that finds him running helplessly through the battlefield, looking for the brotherhood but only finding tragedy, death, loss and horror. The film’s shooting of this scene brilliantly allows the chaos to gradually fade away, giving us an image of the Cross framed against all of the death around him, and ultimately leading him into the silence of what remains, alone with the demons of his imagination and his experience. All except for a single white horse that dots the battlefield, which contrasts with a rising figure cloaked in black. This is described by Edith as trench fever, the images given to someone scarred by what he has seen on the battlefield. It is out of this then that the light is able to shine amidst the darkness, not by doing away with the darkness, but by placing it into context of the larger story. Life is both light and darkness which are constantly at war, both within us and around us. And it is our ability to give words to this reality, both hopeful and devastated, heartbroken and joyful, that allows us to enter into this as a story, one in which we find ourselves, and one in which we find ourselves in relationship to others and the world around us. As we walk through the final scenes of the film, we find that Tolkien is not just to be one voice, but rather the voice of the brotherhood. Death can make us loatheless and helpless as individuals, as Geoffrey says, but it cannot put an end to the immortal four, the stuff that gives such a word its meaning. As the Priest says surveying the darkness, he speaks the liturgy because there is a comfort in ancient things that lie beyond our comprehension, and the language of this liturgy then becomes the very thing that can speak meaning and beauty into the darkness, uncovering the light the lies within us, that is being protected in our hearts.

It is out of this then that the light is able to shine amidst the darkness, not by doing away with the darkness, but by placing it into context of the larger story. Life is both light and darkness which are constantly at war, both within us and around us. And it is our ability to give words to this reality, both hopeful and devastated, heartbroken and joyful, that allows us to enter into this as a story, one in which we find ourselves, and one in which we find ourselves in relationship to others and the world around us. As we walk through the final scenes of the film, we find that Tolkien is not just to be one voice, but rather the voice of the brotherhood. Death can make us loatheless and helpless as individuals, as Geoffrey says, but it cannot put an end to the immortal four, the stuff that gives such a word its meaning. As the Priest says surveying the darkness, he speaks the liturgy because there is a comfort in ancient things that lie beyond our comprehension, and the language of this liturgy then becomes the very thing that can speak meaning and beauty into the darkness, uncovering the light the lies within us, that is being protected in our hearts. From out of the war we begin to gain a clearer picture of what it is that Tolkien has attached his words to, the stuff that gives him meaning. The pictures of the family by his bedside merge with the nighttime chat with his new family, the relationship with Edith and their now children. In another one of my favorite scenes, we find Edith challenging Tolkien as they sit on the steps under the night sky, the one who once wrote for pleasure and passion and now feels pointless and where language has lost its meaning, to decide what he wants from his stories, his writing. Find its meaning or abandon it. Here he returns to where the four of the brotherhood used to meet with Geoffrey’s unreleased poetry in hand. And then he returns home with Edith and his children, once again amidst nature, the images of the trees and the light that has been held captive and protected in his heart. As his family asks him what his story is about, Tolkien is finally ready to to attach his words to what is most meaningful to him. It is a story about treasure, and the treasure is love, companionship, friendship, light and dark weaved together to create something beautiful. It is a story about a quest and a journey, a fellowship, our fellowship with one another and with nature and with God.

From out of the war we begin to gain a clearer picture of what it is that Tolkien has attached his words to, the stuff that gives him meaning. The pictures of the family by his bedside merge with the nighttime chat with his new family, the relationship with Edith and their now children. In another one of my favorite scenes, we find Edith challenging Tolkien as they sit on the steps under the night sky, the one who once wrote for pleasure and passion and now feels pointless and where language has lost its meaning, to decide what he wants from his stories, his writing. Find its meaning or abandon it. Here he returns to where the four of the brotherhood used to meet with Geoffrey’s unreleased poetry in hand. And then he returns home with Edith and his children, once again amidst nature, the images of the trees and the light that has been held captive and protected in his heart. As his family asks him what his story is about, Tolkien is finally ready to to attach his words to what is most meaningful to him. It is a story about treasure, and the treasure is love, companionship, friendship, light and dark weaved together to create something beautiful. It is a story about a quest and a journey, a fellowship, our fellowship with one another and with nature and with God. My introduction to Director Kelly Reich was her film Certain Women (2016), an incredibly nuanced depiction of four strong willed women who are all different in character but whom share in a visible and felt struggle to overcome the burden of sexism and oppression. The film brilliantly fuses together three different sources under a singular vision in order to bring these character lines together in one cohesive and masterfully crafted story.

My introduction to Director Kelly Reich was her film Certain Women (2016), an incredibly nuanced depiction of four strong willed women who are all different in character but whom share in a visible and felt struggle to overcome the burden of sexism and oppression. The film brilliantly fuses together three different sources under a singular vision in order to bring these character lines together in one cohesive and masterfully crafted story. In the opening shot, Reichardt features a slow, almost laborious shot of a lone ship trudging down a river. It’s simple, spacious, and basically devoid of surrounding activity. She employs this basic image as a way of anchoring her story in a narrative that transcends time and place, both in the imagery it evokes and in how it provides this central and establishing movement from the present day to the past.

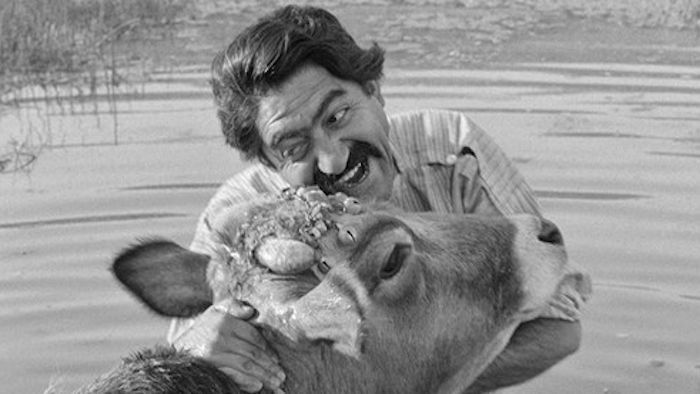

In the opening shot, Reichardt features a slow, almost laborious shot of a lone ship trudging down a river. It’s simple, spacious, and basically devoid of surrounding activity. She employs this basic image as a way of anchoring her story in a narrative that transcends time and place, both in the imagery it evokes and in how it provides this central and establishing movement from the present day to the past. One of the most striking things about the portrait that Reichhardt creates here through these two working images, one of modernity looking backwards, or uncovering history, and the other looking forward anticipating what lies ahead, is how she imagines it within a landscape of diverse peoples, all coexisting around this single cow. The cow itself stands as a colorful and resonant symbol both of the growing bond between Cookie and King-Lu, but also of the nature of progress, it’s milk providing the means of sustenance, cooperation and care, but also demonstrating the essential image of opportunity, the chance for one to establish ones self and get ahead in the world by using the milk to gain a foothold in a competitive environment. The most interesting part of Cookie’s character, and King-Lu for that matter, is that they both imagine from their individual vantage points sitting beneath the shadow of others, that it is okay, then, given this competitive and unfair environment, to engage in certain activities or make certain choices that will allow them to get ahead. This moral line is crossed somewhat nonchalantly, in a matter of fact way that emulates the daily chore of gathering mushrooms and foods from the forest. This is simply what one needs to do. When the milk belongs to the haves, we must rightly take some of the milk in order to help ourselves gain a foothold, to gain some level of significance in this world and be seen with some respect.

One of the most striking things about the portrait that Reichhardt creates here through these two working images, one of modernity looking backwards, or uncovering history, and the other looking forward anticipating what lies ahead, is how she imagines it within a landscape of diverse peoples, all coexisting around this single cow. The cow itself stands as a colorful and resonant symbol both of the growing bond between Cookie and King-Lu, but also of the nature of progress, it’s milk providing the means of sustenance, cooperation and care, but also demonstrating the essential image of opportunity, the chance for one to establish ones self and get ahead in the world by using the milk to gain a foothold in a competitive environment. The most interesting part of Cookie’s character, and King-Lu for that matter, is that they both imagine from their individual vantage points sitting beneath the shadow of others, that it is okay, then, given this competitive and unfair environment, to engage in certain activities or make certain choices that will allow them to get ahead. This moral line is crossed somewhat nonchalantly, in a matter of fact way that emulates the daily chore of gathering mushrooms and foods from the forest. This is simply what one needs to do. When the milk belongs to the haves, we must rightly take some of the milk in order to help ourselves gain a foothold, to gain some level of significance in this world and be seen with some respect. Even more interesting is the fact that Reichardt draws this out within a landscape dotted with all kinds of people, from the settlers, to the Chinese Immigrant to the indigenous peoples. This sense of progress seems to be making its way up through this collage of peoples, providing a compelling picture to carry over into the present day picture of these two indistinguishable skeletons lying side by side. In this sense, the emerging social divide, the essential reality of those on the bottom and those on the top, does not discriminate.

Even more interesting is the fact that Reichardt draws this out within a landscape dotted with all kinds of people, from the settlers, to the Chinese Immigrant to the indigenous peoples. This sense of progress seems to be making its way up through this collage of peoples, providing a compelling picture to carry over into the present day picture of these two indistinguishable skeletons lying side by side. In this sense, the emerging social divide, the essential reality of those on the bottom and those on the top, does not discriminate. It’s an astounding vision that Reichardt presents here, one of two people across ethnic lines being bonded together in struggle, and surrounded by others on all sorts of potential sides of this struggle. But what pulls these two skeletons back into the pages of history as fully fleshed out persons is the image of the cow. The cow is both a hopeful image and a damning one, depending on which perspective we are looking from, either ahead from the past or backwards from history. What’s interesting about the image that looks backwards is that, in some sense it is equally hopeful. This image of two people from diverse backgrounds rendered indistinguishable as skeletons imagines a better future that still could be. But it must be a future built on our true understanding and recovery of the past. How we imagine the Cow as a symbol for our current economic system, and how the Cow is used to achieve our dreams and our imaginings of prosperity and progress, is one of the most important imaginative processes that we can engage in today. This is something that needs to be reformed and redeveloped as we choose to consider the past. Caught between the admiration and appreciation and seeming worship of the Cow is the stuff that eventually leads everything to spiral into chaos in the film, ultimately built by way of competition and capitalist ideals and fueled by an awareness of social placement and division and the human need to belong.

It’s an astounding vision that Reichardt presents here, one of two people across ethnic lines being bonded together in struggle, and surrounded by others on all sorts of potential sides of this struggle. But what pulls these two skeletons back into the pages of history as fully fleshed out persons is the image of the cow. The cow is both a hopeful image and a damning one, depending on which perspective we are looking from, either ahead from the past or backwards from history. What’s interesting about the image that looks backwards is that, in some sense it is equally hopeful. This image of two people from diverse backgrounds rendered indistinguishable as skeletons imagines a better future that still could be. But it must be a future built on our true understanding and recovery of the past. How we imagine the Cow as a symbol for our current economic system, and how the Cow is used to achieve our dreams and our imaginings of prosperity and progress, is one of the most important imaginative processes that we can engage in today. This is something that needs to be reformed and redeveloped as we choose to consider the past. Caught between the admiration and appreciation and seeming worship of the Cow is the stuff that eventually leads everything to spiral into chaos in the film, ultimately built by way of competition and capitalist ideals and fueled by an awareness of social placement and division and the human need to belong. In exploring Iran’s important cinematic history, the most striking characteristic is the overwhelming presence of a liberated cinema which, for example, boasts an incredible representation of women in cinema, but which also bears the mark of a heavily oppressed and marginalized industry (heavy censorship).

In exploring Iran’s important cinematic history, the most striking characteristic is the overwhelming presence of a liberated cinema which, for example, boasts an incredible representation of women in cinema, but which also bears the mark of a heavily oppressed and marginalized industry (heavy censorship). A CINEMA IN CONTEXT

A CINEMA IN CONTEXT A GROWING NATIONAL IDENTITY

A GROWING NATIONAL IDENTITY New Wave and New Iranian Cinema: Distinct Styles and Modern Voices

New Wave and New Iranian Cinema: Distinct Styles and Modern Voices It would be soon after that we find the development of The College of Dramatic Arts, (1963), and the infamous story of The Cow (directed by Masoud Kimiai and Darius Mehrjui), the film that was smuggled out helping to establish the New Wave as a distinct New Iranian Cinema with a continued emphasis on a visual literacy, poetic imagery, and a fusion of fiction and realism. And it is out of this that we find the Iranian Revolution redefining the landscape as a whole. I found this lengthy descriptive from the Tavoos Quarterly regarding this transitioning from the first period to the second period to be helpful:

It would be soon after that we find the development of The College of Dramatic Arts, (1963), and the infamous story of The Cow (directed by Masoud Kimiai and Darius Mehrjui), the film that was smuggled out helping to establish the New Wave as a distinct New Iranian Cinema with a continued emphasis on a visual literacy, poetic imagery, and a fusion of fiction and realism. And it is out of this that we find the Iranian Revolution redefining the landscape as a whole. I found this lengthy descriptive from the Tavoos Quarterly regarding this transitioning from the first period to the second period to be helpful: