The best that can be said of Irish cinema today is that it certainly exists. Even with its

strata of ‘worthy’ and ‘unworthy’ films, its commercial entertainments and its dark

dramas, Irish film at least now produces enough films for there to be such divisions in the first place.

– The identity of an Irish cinema by Dr. Harvey O’Brien

Brooklyn, John Crowley’s internationally celebrated Irish film from 2015, features a recognizable and common distinctive among Irish film- the relationship between a longing for a distinctive Irish culture and presence and the reality of it’s prolonged Diaspora. The tension between these two sometimes complimentary and often opposing cultural forces still exists today even as Ireland’s modern cinematic landscape has managed to grow a stronger sense of identity, with some animosity existing between the Irish and Irish-Americans/Canadians (for example) who like to claim they are Irish. As one writer put it, as this conflict grew, more and more it became an obvious struggle between empire on one side and capitalism on the other.

Brooklyn, John Crowley’s internationally celebrated Irish film from 2015, features a recognizable and common distinctive among Irish film- the relationship between a longing for a distinctive Irish culture and presence and the reality of it’s prolonged Diaspora. The tension between these two sometimes complimentary and often opposing cultural forces still exists today even as Ireland’s modern cinematic landscape has managed to grow a stronger sense of identity, with some animosity existing between the Irish and Irish-Americans/Canadians (for example) who like to claim they are Irish. As one writer put it, as this conflict grew, more and more it became an obvious struggle between empire on one side and capitalism on the other.

FAMINE AND THE DIASPORA

Ireland’s rocky cinematic history begins in the way most nations do, with the first Lumiere images making their way to the Country in the 1890’s. What is interesting about these images is that they reflected a brief period of optimism for a people people who had lived through the tragedy of the Potato Famine. These images would soon give way to violence and more despair.

And yet, these picturesque depictions of the early emergence of the moving image would become an important symbol for Irish cinema, the product of a small island and a modest population. Given how the Potato Famine had displaced its people to foreign territory, the struggle of early Irish cinema would set the tone for years to come, forcing Irish film to depict Ireland from a distance. As these stories evolved, they came to depict the immigrants story somewhere between a love and longing for the homeland and the promise of more prosperous conditions elsewhere. And while the Country continued to struggle on a socio-political level, what is clear today is how important Irish cinema would become to protecting and developing a true Irish heritage. As the Country went so did its cinematic presence, and it becomes clear looking back, and even looking at Ireland today, that where Ireland was able to establish a localized industry and film community, Country and people were also at their strongest.

WAR, CIVIL WAR, CULTURAL IDENTITY AND FURTHER DIASPORA

With World War 1 and the fight for independence just around the corner, Irish cinema would suffer the same fate as so many Countries around the world. As the war wreaked havoc on Countries and cultures and economies, the loss of cultural and national identity became a byproduct. As the war ended, cinema would go on to play a massive role in the reconstruction of this identity, and thus the Country, around the world, including in Ireland.

What makes Ireland’s story unique from places like Italy and France is that they would find themselves once again a decimated community being thrust into yet another war, this time the civil war for Independence. With the Country already struggling to reclaim its people, something that had plagued even the optimism of James Joyce opening Ireland’s first cinema in Dublin in the early 1900’s, those films coming largely from abroad and/or attracting foreign filmmakers to film in Ireland rather than developing Irish films and Directors. Even one of Ireland’s earliest and most popular films of the early silent era, The Lad From Old Ireland made by the newly established Kalem Film Company, was an example of a film that had more connection to abroad. And time would reveal that even though the Kalem Film Company was based in Ireland it had very little to do with Ireland or growing Irish identity itself (closing up shop in 1914).

THE FILM COMPANY OF IRELAND AND THE CONTINUED FIGHT FOR IDENTITY

The Film Company of Ireland (http://filmireland.net/2017/06/14/early-irish-cinema-a-new-industry-the-film-company-of-irelands-first-season/) attempted to change the narrative that had been set by the Diaspora and Ireland’s international sprawl, opening in 1915 and developing in the early post war era before facing immense struggle in the face of the civil war. The film Knocknagow, which released in 1918, is notable for its attempt to reestablish the Irish story and an Irish mythology. One note said that film was intentional in competing against the American film Birth of a Nation, apparently even outgrossing it. And while the company would not survive the civil war (their most successful film, Willy Reilly and His Colleen Bawn, coming right before its demise), it would pave the way for important policies and movements following their Independence.

Another one of the most recognizable aspects of Irish film is its relationship to Ireland’s Protestant-Catholic past and its relationship to National politics with the ongoing division of North and South. Of note is something called the “Censorship of Films Act” (https://www.tcd.ie/irishfilm/censor/), a policy which basically came to determine the character of truly Irish film according to “Catholicism and republicicicisim.” On the flip side, this would establish the means by which film could also push back on these things on an artistic, and therefore cultural level.

This policy was established in 1923, and it would connect later to the National Film Institute (https://ifi.ie/about/history/), an institution created by the marriage of Church and State to uphold Irish Catholic vision and values in film as part of their National identity. This comes in the face of the still ongoing struggle to separate Irish Identity from the dominating pressure of foreign and international presence, such as The Film Society of Ireland, an independent film company concerned with bringing international film to Ireland. What was clear in Ireland was that while Irish filmmakers abroad and international film efforts coming to Ireland to take advantage of their landscape did exist, in order to establish a National identity and culture they needed a way to define that story and that identity according to their own voice. Theater and literature had a strong presence in Irish culture, but the reach of cinema in the modern age proved most necessary to develop now, something that kept evading them even as Countries like Italy had seen a resurgence in cinema and the strengthening of their people and Nation. So while censorship is never a great thing, the one positive that did (and does) come out of it is the ability to develop a unifying ethos. The National Film Institute strengthened the relationship between the Irish people, the Government and the Film Industry, thus giving them a tangible place on which to begin defining what it means to be Irish.

It is out of this that Ardmore film studios would emerge, which as one article put it, “was the Irish Government’s first serious attempt to encourage the development of an Irish Film Industry, a modern studio facility in Co. Wicklow suitable for both national and international production. Ardmore was intended as a signal to the world that Irish cinema had a place on the international stage…”

FROM STRUGGLE TO IDENTITY- IRISH CINEMA EMERGES

As I continue to travel the world through cinema in 2020 I am continually shocked by just how big of an impact the emergence of television had on the global film industry. It is easy to assume that television was simply the latest incarnation of a constantly evolving industry (similar to how we view streaming), but that misses the context of how television impacted these Countries. What is often missed is the many shadows that so many of these Countries had to emerge from, particularly when it comes to wars both global and internal, and how vital the film industry was to rebuilding these Countries in times of great uncertainty. The truth about television is that it has never and does not play a similar role. In fact, in so many of these Countries it is had the opposite and adverse affect. Because of the nature of how television works it tends to decentralize rather than unify, blurring lines between art and its relationship to national identity. It simply does not contain the same impact and definable cultural force that film is able to have on the development and health of a Country.

At the same time, television has consistently placed immense pressure on the film industries around the world which have been so integral to protecting and building a Countries ethos and identity, and there is ample evidence to show that as the film industry goes, so does the Country in the modern age. This is at least in (no small) part due to the fact that one of the great shifts of the modern age is away from the kind of cultural touchpoints that used to bring people together (such as live theater). Cinema plays the role it does precisely because it has the ability to bring people together around these collective stories of identity and form in the way other artforms cannot. Films can hold national identity in one hand and establish that on international soil with the other.

So it was of no surprise to me then to discover that Ireland faced a similar narrative. As John Ford would release one of Ireland’s most defining films (A Quiet Man) in 1952, the rise of television would, as one writer put it, have “a disastrous affect on Irish Identity, combining with the decline of cinema.” And yet, the inspiration of the Irish cinematic story is one that makes my own Irish-Canadian heritage jealous. As we enter the 1970’s, we see a reinvigorating and hard nosed movement to not let cinema die and to breathe into it a new commitment to using it to shed light on the Irish people and identity. And while Irish Cinema today is a shadow of what, say, American Cinema represents in content and numbers, their conviction to the artform in the face of consistent outside pressures (like streaming) actually stands taller in its relevance. With the pride of cinema comes a pride of Irish heritage and a stronger and more unified Country, something doubly important in a land still divided. The Film Act of 1970 allowed Irish Film to expand and to grow (http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20120621-travelwise-the-evolution-of-irish-cinema), while the Irish government was one of the first and early adapters of a film tax initiative. The films that emerged from this became what is known as the Irish First Wave, demonstrating a fresh vision for art and Country.

“What all of these New Wave films have in common is their desire to challenge what had gone before them in cinematic terms. These films aggressively debunked stereotypical images of Ireland and Irish people on film and sought to challenge audiences to see Ireland in a different light.”

The future continued (and continues) to have its challenges of course, particularly in the eventual demise of The Irish Film Board in 1987 and the loss of that unifying voice. But the persistence of the Irish people resulted in films like My Left Foot (Jim Sheridan), The Crying Game (Neil Jordan), The Commitments (Alan Parker), all independent Irish products, paving the way for the rebirth of The Irish Film Board in 1993. Fast forward to today and you have an industry that, not unlike the earlier days of Italian cinema, has found a way to grow in genres, proving to leave quite a footprint in animation (Cartoon Saloon) and even in the likes of horror. But the most important undercurrent appears to be this-

“While big-budget international productions keep crews working and are enormously valuable to the country, it is the indigenous industry that is at the heart of creating opportunity and giving skills and experience to Irish producers, directors, writers and crew, telling the stories that emerge from Irish-based talent.”

As cinema goes, so does Irish identity. And like modern Ukraine, the stronger their identity the stronger Irish Cinema is becoming. It is proving that it doesn’t need to be America in order to succeed, boasting the highest rate of cinema admissions in Europe. It can, simply, be Ireland.

*For my Film Travels, here is the full list of Irish Films I have seen. It is a working and ranked list available on Letterboxd:

https://letterboxd.com/davetcourt/list/film-travels-2020-ireland/

SOURCES

Barton, Ruth, Irish National Cinema (Routledge, 2004)

McIlroy, Brian, Shooting to Kill: Filmmaking and the Troubles in Northern Ireland

(Flicks, 1998)

McLoone, Martin, Irish Film: The Emergence of a Contemporary Cinema (BFI, 2000)

http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20120621-travelwise-the-evolution-of-irish-cinema

http://filmireland.net/2017/06/14/early-irish-cinema-a-new-industry-the-film-company-of-irelands-first-season/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cinema_of_Ireland

https://www.volta.ie/#!/page/608/a-short-history-of-irish-cinema

https://www.ifi.ie/downloads/history.pdf

The identity of an Irish cinema by Dr. Harvey O’Brien

The RHYTHM SECTION, a late January holdover, turned out to be a pleasant surprise. Suffering from a lack of advertising, poor critical reception and breaking the kind of records you don’t want to break (making the least amount of money on a weekend for a film on as many screens as it had), this one was bound to get shoved under the rug and quickly forgotten. Which is a shame. Blake Lively gives an inspired performance, it features one of the great car chase scenes in recent memory, and as thrillers go its competence actually gives way to some compelling moral questions.Worth checking out when it becomes available at home.

The RHYTHM SECTION, a late January holdover, turned out to be a pleasant surprise. Suffering from a lack of advertising, poor critical reception and breaking the kind of records you don’t want to break (making the least amount of money on a weekend for a film on as many screens as it had), this one was bound to get shoved under the rug and quickly forgotten. Which is a shame. Blake Lively gives an inspired performance, it features one of the great car chase scenes in recent memory, and as thrillers go its competence actually gives way to some compelling moral questions.Worth checking out when it becomes available at home. MOTHERLESS BROOKLYN, a film that also ended up largely forgotten and mostly missed in theaters, found its release on VOD this month. To be honest, I was mixed on the film when I saw it on the big screen, but a rewatch this month grew my appreciation for it on a number of levels. I loved the New York Noir setting, and I really appreciated how Edward Norton, in his Directorial debut, shows a real knack for being able to blend together theme, performance and structure in a very methodical and natural way. He has a real future ahead of him behind the camera.

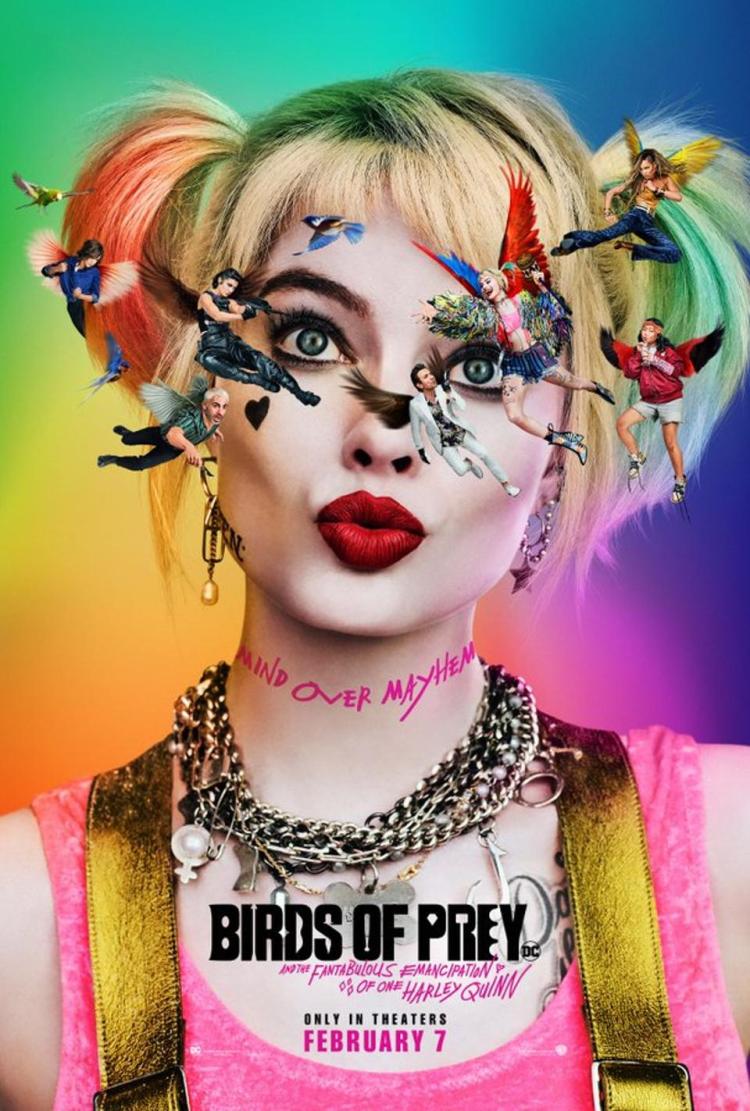

MOTHERLESS BROOKLYN, a film that also ended up largely forgotten and mostly missed in theaters, found its release on VOD this month. To be honest, I was mixed on the film when I saw it on the big screen, but a rewatch this month grew my appreciation for it on a number of levels. I loved the New York Noir setting, and I really appreciated how Edward Norton, in his Directorial debut, shows a real knack for being able to blend together theme, performance and structure in a very methodical and natural way. He has a real future ahead of him behind the camera. Back on the big screen front, BIRDS OF PREY (AND THE FANTABULOUS EMANCIPATION OF ONE HARLEY QUINN) is a TON of fun. It proved that when you have someone like Margot Robbie breathing life into a problematic franchise (Suicide Squad), her powerful vision, an inspired and dominating lead performance, and a willingness to scale back the budget and get a bit more creative went a long way to making this work as well as it did.

Back on the big screen front, BIRDS OF PREY (AND THE FANTABULOUS EMANCIPATION OF ONE HARLEY QUINN) is a TON of fun. It proved that when you have someone like Margot Robbie breathing life into a problematic franchise (Suicide Squad), her powerful vision, an inspired and dominating lead performance, and a willingness to scale back the budget and get a bit more creative went a long way to making this work as well as it did. Also just released to the big screen are two undeniable gems, including the winning romance THE PHOTOGRAPH, a subtle cinematic work that is chalk full of wonderful beats that move us from comedy to mystery to dramatic concern. It’s quiet and not in any way flashy, but it gradually draws you in.

Also just released to the big screen are two undeniable gems, including the winning romance THE PHOTOGRAPH, a subtle cinematic work that is chalk full of wonderful beats that move us from comedy to mystery to dramatic concern. It’s quiet and not in any way flashy, but it gradually draws you in.

Not only did it make history in terms of being the first foreign film to do a lot of things on the night, but the win translated into a wonderful and endless line of dialogue and articles and conversation about foreign films in general, the reward and challenge of engaging subtitles, and the nature of art on a global level.

Not only did it make history in terms of being the first foreign film to do a lot of things on the night, but the win translated into a wonderful and endless line of dialogue and articles and conversation about foreign films in general, the reward and challenge of engaging subtitles, and the nature of art on a global level.

And in case you missed it (as I unfortunately did due to a rough February personally speaking), one of the many reasons to consider supporting our local arthouse, CINEMATHEQUE, is this past months AFRO-PRAIRIE FILM FESTIVAL. It featured a stellar lineup and is one the only places to catch some smaller releases (such as Les Miserables and Clemency). The festival is over, but look for smaller films and festivals to screen here all year round. It always promises to be a very involved and enthusiastic crowd of fellow cinephiles.

And in case you missed it (as I unfortunately did due to a rough February personally speaking), one of the many reasons to consider supporting our local arthouse, CINEMATHEQUE, is this past months AFRO-PRAIRIE FILM FESTIVAL. It featured a stellar lineup and is one the only places to catch some smaller releases (such as Les Miserables and Clemency). The festival is over, but look for smaller films and festivals to screen here all year round. It always promises to be a very involved and enthusiastic crowd of fellow cinephiles. In terms of March releases though, the month kicks off with a bang, featuring a new installment from Pixar called ONWARD. We knew very little about this film seeing as it was a largely unknown original currently being overshadowed by Pixar’s second more anticipated original to release later this year (SOUL). Early word appears to suggest that tempered expectations will work in its favor.

In terms of March releases though, the month kicks off with a bang, featuring a new installment from Pixar called ONWARD. We knew very little about this film seeing as it was a largely unknown original currently being overshadowed by Pixar’s second more anticipated original to release later this year (SOUL). Early word appears to suggest that tempered expectations will work in its favor.

After 4 full seasons of contemplating the afterlife using a good blend of humor, emotion and chemistry, the much beloved series The Good Place came to a close this past week. Known for its ability to take deep philosophical and theological ideas and break them down into bite size questions and relevant conversation that anyone can understand and relate to regardless of religious affiliation, the show was consistently striving to present the idea of the afterlife as a mystery to explore rather than a fact to exploit.

After 4 full seasons of contemplating the afterlife using a good blend of humor, emotion and chemistry, the much beloved series The Good Place came to a close this past week. Known for its ability to take deep philosophical and theological ideas and break them down into bite size questions and relevant conversation that anyone can understand and relate to regardless of religious affiliation, the show was consistently striving to present the idea of the afterlife as a mystery to explore rather than a fact to exploit. As someone who has long struggled with anxiety and depression, including suicidal thoughts, these final episodes left me in a pretty dark place. In his wonderful article on the finale,

As someone who has long struggled with anxiety and depression, including suicidal thoughts, these final episodes left me in a pretty dark place. In his wonderful article on the finale,  Say what you will about the Oscars, and to be clear, every year around this time cinephiles (like me) do seem to have a good deal to say (it’s easy to be cynical about the idea of Hollywood celebrating Hollywood after all), b

Say what you will about the Oscars, and to be clear, every year around this time cinephiles (like me) do seem to have a good deal to say (it’s easy to be cynical about the idea of Hollywood celebrating Hollywood after all), b 1. Underwater (3.5)– Really happy to see that this surprisingly fun horror sci-fi action film is still holding on to a couple screens. Starring the often misunderstood and undersold Kristen Stewart, the film evokes serious Alien vibes as it manages it’s way through some superb set pieces with a subtle interest in themes of female empowerment.

1. Underwater (3.5)– Really happy to see that this surprisingly fun horror sci-fi action film is still holding on to a couple screens. Starring the often misunderstood and undersold Kristen Stewart, the film evokes serious Alien vibes as it manages it’s way through some superb set pieces with a subtle interest in themes of female empowerment.

3. Dolittle (3)– I don’t think anyone will be talking about this one come the end of the year, but children’s stories like this tend to be a rarity these days, and ratings seem to suggest that this is something general audiences are appreciating and responding to. It has done decently well, even if it has a long road to travel in making up its sizable budget. For me its blend of quirky interactions, sentimentality, an inspired performance by Downy, adventure, and a solid message about our relationship to the created world was enough to transport me into its story and put a smile on my face.

3. Dolittle (3)– I don’t think anyone will be talking about this one come the end of the year, but children’s stories like this tend to be a rarity these days, and ratings seem to suggest that this is something general audiences are appreciating and responding to. It has done decently well, even if it has a long road to travel in making up its sizable budget. For me its blend of quirky interactions, sentimentality, an inspired performance by Downy, adventure, and a solid message about our relationship to the created world was enough to transport me into its story and put a smile on my face. 4. The Gentlemen (3.5)– Directed by Guy Ritchie, it should not be undersold that this is an original project. With its blend of humor, edgy characters and scripted fun, this is one that has some very real and very rewatchable appeal.

4. The Gentlemen (3.5)– Directed by Guy Ritchie, it should not be undersold that this is an original project. With its blend of humor, edgy characters and scripted fun, this is one that has some very real and very rewatchable appeal. 5. Rythym Section (3.5)– A solid thriller with a really good lead performance and strong supporting cast. Don’t let the headlines of this film’s record breaking box office slump deter you. This is one that is unfortunately getting lost in the shuffle and is far better than those appearances might lead you to believe.

5. Rythym Section (3.5)– A solid thriller with a really good lead performance and strong supporting cast. Don’t let the headlines of this film’s record breaking box office slump deter you. This is one that is unfortunately getting lost in the shuffle and is far better than those appearances might lead you to believe. 7. Weathering With You– The follow up to the beautiful Your Name, this anime film from Japan will be a solid candidate for animated film of the year come December. With its striking visual presence and solid story, it is worth taking the time to check out on the big screen while you can.

7. Weathering With You– The follow up to the beautiful Your Name, this anime film from Japan will be a solid candidate for animated film of the year come December. With its striking visual presence and solid story, it is worth taking the time to check out on the big screen while you can. 8. Just Mercy (4)- An emotional crowd pleaser with an important message, this popular drama is still playing on a couple screens. It is proving to really resonate with general audiences, and is benefiting from a strong advertising campaign. If you haven’t had a chance to check it out, keep it on your radar. It should be making its way to VOD fairly soon.

8. Just Mercy (4)- An emotional crowd pleaser with an important message, this popular drama is still playing on a couple screens. It is proving to really resonate with general audiences, and is benefiting from a strong advertising campaign. If you haven’t had a chance to check it out, keep it on your radar. It should be making its way to VOD fairly soon. 1. 3 high profile Horror films are set to take North American cinema by storm- The Lodge, which has already garnered rave reviews, the much anticipated The Invisible Man (featuring the always incredible Elizabeth Moss), and the intriguing but still unknown Fantasy Island. My money is on The Lodge, but watch out for the other two to make a splash.

1. 3 high profile Horror films are set to take North American cinema by storm- The Lodge, which has already garnered rave reviews, the much anticipated The Invisible Man (featuring the always incredible Elizabeth Moss), and the intriguing but still unknown Fantasy Island. My money is on The Lodge, but watch out for the other two to make a splash. 2. The long awaited release of Portrait of a Lady on Fire is almost upon us. This international film made quite an impression during festival season last year, and its delayed release has been frustrating more than a few of us cinephiles. Now we will finally get to see what all the fuss is about.

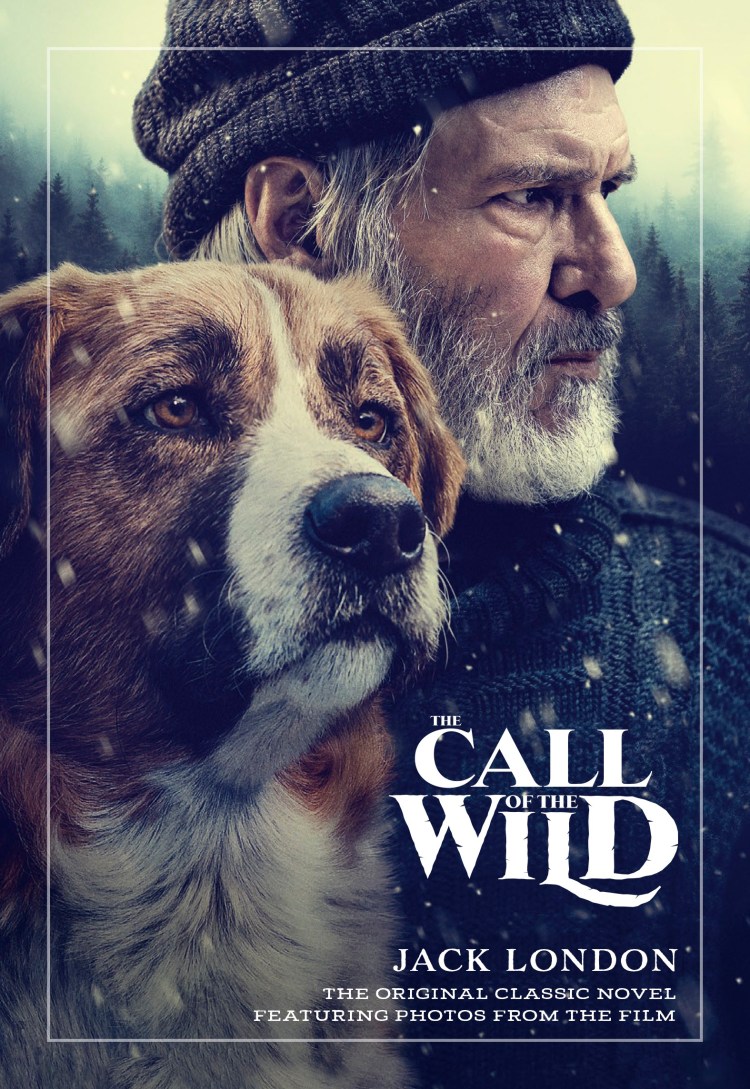

2. The long awaited release of Portrait of a Lady on Fire is almost upon us. This international film made quite an impression during festival season last year, and its delayed release has been frustrating more than a few of us cinephiles. Now we will finally get to see what all the fuss is about. I’m kind of still intrigued about Sonic the Hedghog, and Bloodshot looks like the real deal, but the one I am most excited about is the coming adaptation of The Call of the Wild. I loved the novel, am a sucker for these types of wilderness films with animal characters at their center, and love Harrison Ford.

I’m kind of still intrigued about Sonic the Hedghog, and Bloodshot looks like the real deal, but the one I am most excited about is the coming adaptation of The Call of the Wild. I loved the novel, am a sucker for these types of wilderness films with animal characters at their center, and love Harrison Ford. But just in case you are second guessing Birds of Prey, everything that I have heard so far suggests it’s a super fun romp with an unexpected edge.

But just in case you are second guessing Birds of Prey, everything that I have heard so far suggests it’s a super fun romp with an unexpected edge. 4. Two small time projects with big time appeal- The Photograph is on my most anticipated list, a quiet love story that explores themes of love and commitment. But the one I am REALLY looking forward to is a film called Wendy. From the Director of the amazing Beasts of the Southern Wild, this is a take on the Peter Pan story that blends a child like perspective and imagination with real world struggle. It looks incredible and promising, and I can’t wait to get swept up into its fantastical vision.

4. Two small time projects with big time appeal- The Photograph is on my most anticipated list, a quiet love story that explores themes of love and commitment. But the one I am REALLY looking forward to is a film called Wendy. From the Director of the amazing Beasts of the Southern Wild, this is a take on the Peter Pan story that blends a child like perspective and imagination with real world struggle. It looks incredible and promising, and I can’t wait to get swept up into its fantastical vision.

12. THE PEANUT BUTTER FALCON

12. THE PEANUT BUTTER FALCON 11. LAST BLACK MAN IN SAN FRANCISCO

11. LAST BLACK MAN IN SAN FRANCISCO 10. AD ASTRA

10. AD ASTRA 9. LIGHT OF MY LIFE

9. LIGHT OF MY LIFE 8. TOLKIEN

8. TOLKIEN 7. THE MAN WHO KILLED HITLER AND THEN BIGFOOT

7. THE MAN WHO KILLED HITLER AND THEN BIGFOOT 6. JOKER

6. JOKER 5. THE FAREWELL

5. THE FAREWELL 4. JO JO RABBIT

4. JO JO RABBIT 3. PARASITE

3. PARASITE 2. ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD

2. ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD 1. A BEAUTIFUL DAY IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD

1. A BEAUTIFUL DAY IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD