My 2020 Film, Writing and Reading Challenge:

Travelling Around the World Through Film, Blog and Book

The Particulars:

International Film Challenge

I’ll be using the full list of Oscar submissions as my base (available here: https://www.screendaily.com/…/full-list…/5133396.article)

Beginning with a Country’s submission from this list, I’ll be doing research on films and Directors etc. from that Country, making a list of necessary and important films and viewing the coinciding projects.

For the reading challenge side of it, I’m hoping to pair books on the history of film and culture within these particular regions with the Country these films are concerned with.

I have no set number or timeline for how long to spend in a given Country, so I will see how far I get.

Integrated Writing and Reading Challenge

I define a film critic primarily as someone who writes/talks about film and who has a base of followers. These two distinctives are what separates a critic from a fan (or hobbiest, or lover, or whatever label best fits for you).

The other side of this is my personal definition of film “criticism”. Anyone who has feelings and thoughts about a film is engaging in criticism, and I think it is important to recognize that criticism at its root is not a negative term. It simply means to think about or assess a films qualities and distinctives.

I love to write and talk about film (criticism), and I engage with critics who have followers because they offer me a place to write and talk with others about film. The best critics I have found encourage a given community to think about the art and the craft of filmmaking in light of our experiences, and the best communities care about providing and sustaining a safe place to express these thoughts with one another

The ongoing challenge of film criticism for those who share a love of film as a critical medium is balancing awareness of the craft with our experience of a film. The danger of engaging film criticism within a functioning community is its penchant to categorize people, opinions and thoughts in terms of who is right or who is wrong. When this persists it creates insiders and outsiders (cliques). I see this happen with film critics. I also see it happen in film communities.

Sadly, in my own experience too often conversation about film gets boiled down to right and wrong, subjective versus objective, and when ones experiences differs from another’s, our default response becomes one of predetermined dismissiveness- I’m glad it worked for you, but it didn’t for me. These types of responses are good for protecting against unnecessary conflict, but they do little to alleviate the existence of insiders and outsiders, and dont help in our understanding of what film “criticism” actually is- conversation rather than opinion. And I am guilty of this same thing myself. Our experience of film should never be something we feel we need to protect or defend, rather it should be something that our mutual conversations look to shape.

The truth is, our awareness of the craft is ALWAYS subservient to our experience of the craft. All objective opinion is measured subjectively. This is the marriage we work within when we participate in the art of conversation together. To see film and film criticism any other way is dishonest and disingenuine, and worse yet can be dismissive and demeaning.

And yet often the pressure does exist within film communities to appear more objective than we are for the sake of being taken seriously in conversation with others. What this leads to though is elitism, always and consistently, and it, by default, provides fuel to the idea that there are insiders and outsiders within this systematized approach to what should be a communal exercise.

What makes film such an important art form is its social component, and the strength of its social component is found in the shared experience and the shared discussion in a way that is not discriminatory. An ability to converse on equal ground is key to our ability to engagement and likewise learn, whether we are a critic or a viewer. This means listening first and speaking second, with emphasis on the fact that conversation depends on this two way street.

In 2019, and as someone who cherishes film, I found myself confronted with the reality of these insider/outsider categorizations. The reality that so much of our social interaction (and sometimes all of it) comes from online forms compounds these categories, largely because they are able to persist in these spaces silently and at a detached distance. We arent responsible for the inclusion and acceptance of others we cannot see, thus it becomes incredibly easy online to feel, rightly or wrongly, that you and your opinions belong and somehow are at the bottom of a perceived, figurative, and also very real at times social ladder. The sad part of the reality is for some, if not many, is that there is shame in admitting that we think or feel this way at all, especially when it comes to communities built around things we are passionate about.

In truth, within the context of online film communities these realities can easily turn thinking and writing about film into a socially driven fear and a challenge rather than a joy. Because film is such a passionate and personal medium, missing the nuance of social interaction is all too common in a virtual world predicated by quick wit, single sentence (lest it succumb to TLDR), story breaking, eye catching, popularized online vernacular. Like too much high art, praise too many blockbusters, write too long, too short, see films too late or too soon, don’t watch enough, watch too many, read the right stuff or the wrong stuff, be emotional or not emotional enough, have a hot take or a dumb take, taken together all of these things can hold significant sway in whether you feel you do or don’t belong in conversation with others and whether you are an insider or outsider in these online communities.

It is the nature of conversation as an art and writing as a form. The first belongs to everyone as a product of being a social creature. The other comes with the baggage of being a given and aquired talent and skill. The problem is that in physical social context we can find like minded individuals more easily. In the online world not all writing is considered equal, and yet writing (and the wit that accompanies it) is a singular and measured form. What follows then when this becomes the dominant form of relating to one another within film communities is the loss of one’s ability to converse on equal grounds as “people”. We are only as good as our ability to converse in written form.

This can be a nasty and awfully hard world to navigate at the best of times, particularly for an artistic medium where experience, and the sharing of those experiences, is such an integral facet of its expression. To be sheltered behind a keyboard means it is that much easier to disappear behind it as well. Write an unpopular opinion or say something too emotional or pen something in the wrong form and the wrong way and it cause you to feel isolated in the virtual eyes of others forever (when most of the time people arent aware this is happening). And if you arent witty or savvy enough or elegant enough to navigate out of these trappings it can feel very defeating and near impossible to avoid this feeling of isolation. It is a powerful force.

And theory and research seems to show that virtual isolation can be even more damaging than physical isolation primarily because it allows us to remain ignorant of its impact and to create the existence of this isolation in particular ways in our own heads that allows it to grow into monstrous forms.

And yes, every group will say that everyone belongs, but everyone who is a part of a community also knows how real the feeling and presence of that isolating social ladder is. There are always people at the top and people at the bottom, and when we translate this to film community and film discussion, what make this doubly destructive is that the medium is one that invites us into conversation, only to make us feel more isolated in response when we feel our online opinions dont measure up. It can feel like we’ve been mislead or duped into a false sense of hope and identity.

It is the challenge for those who experience this to persist in speaking and to find the motivation to keep writing about something that is meaningful to them even when they feel that their opinions dont matter, might be judged or wont be heard. And the reason to keep doing this is because we need this community, and we need to share our experiences with film with one another as part of what it means to be human. One way to ensure this doesnt happen at all is simply not to share and not to write at all, which would be more harmful.

As the world turns and physical social reaction around film becomes less and less common, there remains a desperate need to figure out how to make this online community work. One of the things I am trying to do this year is to rediscover my own voice in this context. I spent so much of 2019 trying to figure out how to balance hanging with the elite of the online film groups I am a part of, and I came to realize that is something I could be chasing after forever. It doesn’t help to make me feel like I belong. If anything it just reminds me of why I dont. So how do I respond? How do I still engage in these communities in a healthy and meaningful way?

First, knowing that it is important for me to feel that I am not writing simply for my own sake or in a vacuum (or in online form, a virtual vacuum), the only true response I can have that is within my control is to continue to commit to reading the work of others. If someone takes the time to write, pens a review, has some thoughts, regardless of who they are or where they are on this social ladder I take the time to read their work from start to finish and genuinely consider it worthwhile. No excuses.

Second, I decided to give far more time to writing this year in a way that best expresses my voice in an honest way. I am someone who is interested in narrative over character and story over performance. I appreciate all aspects of film, but the films that inspire me and the scenes that speak to me are the ones with strong narrative focus and a meaningful story. My hope is to focus back in on that aspect of film and to give more voice to the stories and narratives that stand out to me in 2020 rather than feeling the need to qualify those feelings with certain external polishes (giving lower star ratings, elevating weaknesses to something they aren’t, using certain emphasis) just so that I can feel I can participate in the discussion.

To coincide with this, I am also hoping to work into my reading challenge books on film technique and storytelling methods. It’s been a while since I’ve read one, and I think re-familiarizing myself with the nuts and bolts off narrative structure would be a helpful asset as I write more as well.

And one more thing to add as an aside…

Additional Reading Challenge

I have made a list of books to read that my favorite films are based on/were adapted from to include in my reading challenge for this year as well.

Happy New Years everyone. May it bring more great reads, watches and reflections for you all.

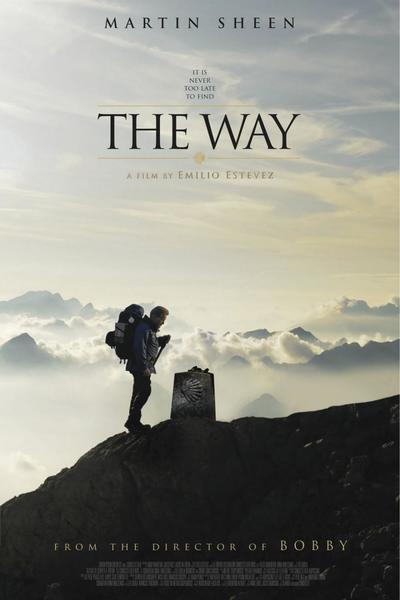

The Way of Jesus

The Way of Jesus For Tom, his change in direction brings him to the possibility of healing and reconciliation. Coming to the foot of the cross, he finds peace in the end once again within the walls of a church. It’s a beautiful and freeing moment where we see him finally fully broken and vulnerable, open to what The Way has to teach him as a forgiven, fully reconciled and hopeful child of God. And it is this moment that frees him to reconcile with his son at the ocean side by spreading his ashes at the final, declarative point of this journey. Not as a way of saying we arrived and been transformed, but as a way of saying we live in the promise of this transformation now even though we are still being made new every single day.

For Tom, his change in direction brings him to the possibility of healing and reconciliation. Coming to the foot of the cross, he finds peace in the end once again within the walls of a church. It’s a beautiful and freeing moment where we see him finally fully broken and vulnerable, open to what The Way has to teach him as a forgiven, fully reconciled and hopeful child of God. And it is this moment that frees him to reconcile with his son at the ocean side by spreading his ashes at the final, declarative point of this journey. Not as a way of saying we arrived and been transformed, but as a way of saying we live in the promise of this transformation now even though we are still being made new every single day. To help celebrate Christmas this year I chose a grouping of films to watch over the Advent season (6 in total), with each film coinciding with one of the virtues that Advent celebrates through the lighting of the candles. The first Sunday is hope, and the second Sunday is Faith. This past Sunday, for which I chose my favorite film of last year “If Beale Street Could Talk”, was Joy. With the emphasis that Advent places on darkness and light, where we arrive at joy in this seasonal and liturgical process is by way of the darkness that helps emphasize the slow and gradual illumination of the light.

To help celebrate Christmas this year I chose a grouping of films to watch over the Advent season (6 in total), with each film coinciding with one of the virtues that Advent celebrates through the lighting of the candles. The first Sunday is hope, and the second Sunday is Faith. This past Sunday, for which I chose my favorite film of last year “If Beale Street Could Talk”, was Joy. With the emphasis that Advent places on darkness and light, where we arrive at joy in this seasonal and liturgical process is by way of the darkness that helps emphasize the slow and gradual illumination of the light. This becomes a pivotal point in the film in which hopelessness then leads to this ultimate picture of hopefulness, the arrival of this expectant child bursting into the world in a grand display of light. It’s an incredible moment, and I think it encapsulates what the joy of Christmas is all about. Into the darkest of places the Christ Child arrives, and in this Child we find the promise of what feels like a still uncertain future. That’s what we hold onto, and that is where we are free to reclaim the joy that this season offers. Not that things will be made right in the here and now or that our problems will be solved. The film brilliantly leaves the idea of him getting out of prison and them getting married and how long they will remain separated as ambiguous. We arent given this information. What we do get to see though is a joy reclaimed through the promise of this child. As she says in the end, “we have the life we have been given, and by (this life) our children can be free.

This becomes a pivotal point in the film in which hopelessness then leads to this ultimate picture of hopefulness, the arrival of this expectant child bursting into the world in a grand display of light. It’s an incredible moment, and I think it encapsulates what the joy of Christmas is all about. Into the darkest of places the Christ Child arrives, and in this Child we find the promise of what feels like a still uncertain future. That’s what we hold onto, and that is where we are free to reclaim the joy that this season offers. Not that things will be made right in the here and now or that our problems will be solved. The film brilliantly leaves the idea of him getting out of prison and them getting married and how long they will remain separated as ambiguous. We arent given this information. What we do get to see though is a joy reclaimed through the promise of this child. As she says in the end, “we have the life we have been given, and by (this life) our children can be free.

Which is precisely what the darkness is imagined to be as well. A disrupter. Only over the course of the film what we come to realize is that what the darkness disrupts is our sense of self reliance, the very thing that opens us up to this desperate and innately driven need of FAITH as the thing that can reorient us towards the light when things feel largely aimless, lost and out of our control. The same faith that can then shine a light into the world at large.

Which is precisely what the darkness is imagined to be as well. A disrupter. Only over the course of the film what we come to realize is that what the darkness disrupts is our sense of self reliance, the very thing that opens us up to this desperate and innately driven need of FAITH as the thing that can reorient us towards the light when things feel largely aimless, lost and out of our control. The same faith that can then shine a light into the world at large. This is what the light does. This is what Christmas celebrates. As we stand looking out over the world with our own existential questions and our own awareness of the darkness in mind, we are able to frame (or reframe) our place in the world not according to our weakness or our strength, but according to the idea that in our weakness we are a part of a grander story.

This is what the light does. This is what Christmas celebrates. As we stand looking out over the world with our own existential questions and our own awareness of the darkness in mind, we are able to frame (or reframe) our place in the world not according to our weakness or our strength, but according to the idea that in our weakness we are a part of a grander story.

The Beauty of A Human Moment

The Beauty of A Human Moment The film is not absent of the despair and struggle and everyday monotony that is so prominent in Roma. There is division and there is the pain of an isolated and oppressed culture. There is the corrupted image of a street that holds in its stone promenades the story of a divided Country. This is the one side of that glass wall. But it doesn’t want to leave us there. It allows the characters to bridge the coldness and the distance in order to give us that sense of closeness, intimacy, warmth and love that its centrals characters, and we if we are honest, so desperately long for.

The film is not absent of the despair and struggle and everyday monotony that is so prominent in Roma. There is division and there is the pain of an isolated and oppressed culture. There is the corrupted image of a street that holds in its stone promenades the story of a divided Country. This is the one side of that glass wall. But it doesn’t want to leave us there. It allows the characters to bridge the coldness and the distance in order to give us that sense of closeness, intimacy, warmth and love that its centrals characters, and we if we are honest, so desperately long for. The Hopeful Work

The Hopeful Work A Street That Paves The Way Forward

A Street That Paves The Way Forward