The sun was getting ready to set, and as we approach the base of the John Seigenthaler Pedestrian Bridge we notice an individual, a woman likely in her mid twenties/early thirties, who is visibly agitated and yelling something seemingly towards someone on the top of the bridge. As we got closer we were able to make out that the string of profanity accompanying this woman’s agitation had something to do with the “black nigger bitches” walking the pedestrian bridge above her.

The sun was getting ready to set, and as we approach the base of the John Seigenthaler Pedestrian Bridge we notice an individual, a woman likely in her mid twenties/early thirties, who is visibly agitated and yelling something seemingly towards someone on the top of the bridge. As we got closer we were able to make out that the string of profanity accompanying this woman’s agitation had something to do with the “black nigger bitches” walking the pedestrian bridge above her.

We don’t know what led to this war of words. What we did know was that this woman, clearly agitated and obviously a little drunk, was now occupying the space by the elevator doors we needed to take to get to the top of the bridge.

Lingering in the shadows for a bit while hoping this lady would eventually give up and go away, we eventually were able to follow behind another middle aged couple for whom this seemed to be “just another day in Nashville”. They saw us following up behind them and quickly ushered us into the elevator doors where we were able to make our way to the top.

Both of us were sweating a little. Of course that might have had something to do with the 30 degree weather in Tennessee. Or the 40 degree weather inside that elevator.

Exiting the elevator we emerged onto the pedestrian bridge to see the group of 5 young, African American adults who had been the source of the ladies ire. And suddenly all 5 of them were turned staring straight at the two of us.

No, wait. They were staring straight past us. At the elevator doors.

Turning around we saw the lady from the ground level had boarded the elevator and was now making her way up.

“Oh shit, oh shit, oh shit” one of the younger ones exclaims.

We share the sentiment.

Caught in the middle, we quickly retreated to the side of the bridge where, at the very least, we would no longer be stuck in the middle. The group of 5 retreated downwards towards the base of the bridge and the agitated woman followed after them. We took the opportunity and quickly started heading for the top of the bridge…

Putting ourselves definitely in the middle of someone shooting a music video.

Or a music something.

There was a conductor, who also happened to be the one working the camera. And in front of him is a man and a woman, one with a keyboard and the other with a guitar, both who look like the came straight out of 1980’s Maranatha Church music video.

The conductor, giving everything he as to breathe life into this music video is getting more and more animated while the musicians keep keep more and more straight faced. Aware that we were most definitely not in Kansas anymore, we nudged our way as best we could past the camera. As I did this I looked for some sort of open box that might indicate these guys are playing up a routine to gain tourist dollars, but there seemed to be nothing of the sort. Just this strange scene playing out in front of us as though we had entered an episode of the twilight zone.

Finally getting past this rather odd state of affairs, I turn my head and suddenly there it is. Music City unfolding right before us bringing a little bit of sanity back into the picture.

Welcome to Nashville!

Nashville in July is hot. I know it’s obvious, but I felt it needed to be said.

A peculiarity about Nashville is that to see this city on a budget, which is a necessity if only because this city of music and museums can easily get expensive and out of control if you let it- nearly everything you will end up doing on a budget puts you outside in the heat.

Which is only to say I’m not sure we would visit again in July. Give me the fall or the winter and a good show though and the stuff that clearly makes this city tick would turn into a great experience. As any good tourist usually does, our exploration of this city started with a jaunt down Broadway where the endless Honky Tonk bars are all vying for the attention of the packed streets. And as the sun sets and the lights come up it only gets livelier.

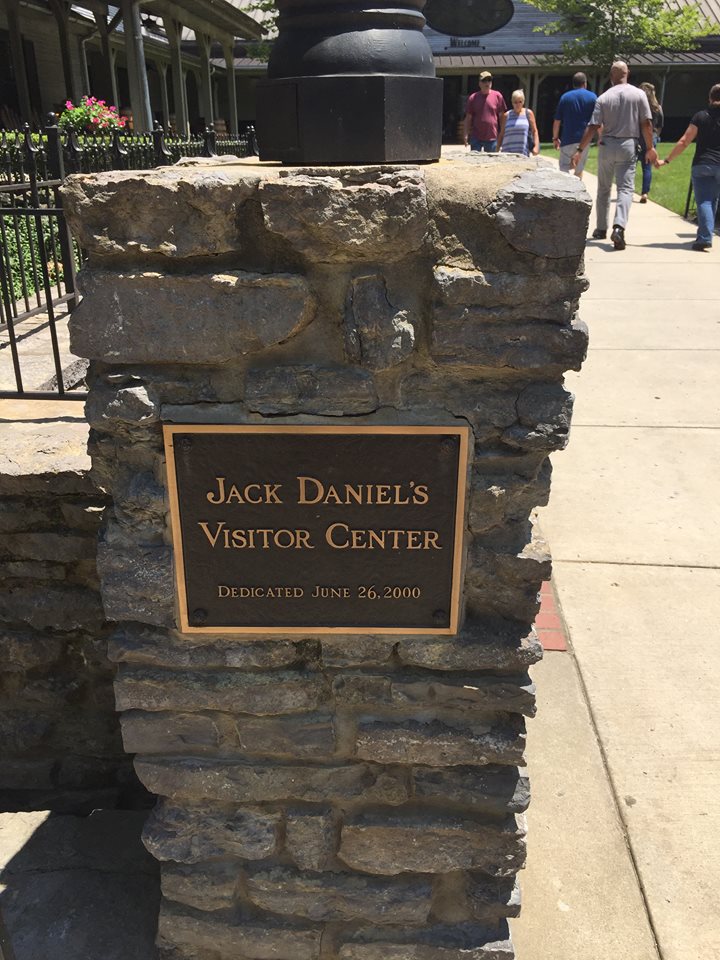

After a drive through South-Eastern Tennessee, which took us through the historic Chattanooga (a fun stop) and Lynchburg (the home of Jack Daniel), we spent the next three days in the Nashville area. Rather than simply reflect on some of what stood out for me in this area, I thought I would do something different for this one and focus more on the vacation than the introspective journey.

Given our approach to the city, I figured I would go through our time in Nashville from the angle of doing Nashville on a budget. It is an expensive city, but it doesn’t have to be. And although ours is just a singular experience, here is at least one perspective on how to see Nashville and maybe save a bit of money while you are doing it:

Tip #1: Take advantage of the free parking

When I was researching Nashville one of the things that kept coming up was that it was hard to find parking and the parking that you can find is either expensive or not available during the day.

One of the most popular pieces of advice I found was to look into parking in one of the lots at the Tennessee Titans Stadium and using the Pedestrian Bridge that sits right beside the stadium to take you right into the heart of downtown (a block away from Broadway). There are (I believe) 2 lots that are free to park in on days where there are no games or other major Stadium events happening. The problem with this, and what this advice did not clearly divulge, is that these spots can be reserved ahead of time. And so unless you are booking way ahead it is tough to actually find an available spot there.

On a fluke though I came across a secondary piece of advice that instructed me not to go into the lots but to instead to enter the Stadium grounds, drive through the lots and turn towards Titans Way, Victory Avenue, or First Street South. All of these streets are either entirely unreserved or have portions that are unreserved and free, unlimited parking on days (both during the days and in the evenings) that are not Stadium event days. And if you don’t find anything on Titans Way (your closest proximity to gain access to the Pedestrian Bridge elevator), just drive up 1st Street and you will find a spot closer to the actual foot of the bridge where you can simply walk up and over to the downtown attractions.

It is also worth noting that parking is free in downtown Nashville after six, but you might have a hard time finding a spot that is closer to the attractions than the stadium lot.

Tip #2: Take the free bus

If you are parking by the Stadium lot (or in the lot) and using the bridge as your entry point into downtown, directly the bridge you will see a bus stop called Music City Star Riverfront Station. There are two buses (the Green and the Blue Line) that you can catch from this station that are free and that make several different stops along the major sights and attractions. The routes overlap at a few points, but there is a map at this station letting you know which one you might want to take.

The only place in the downtown district these buses don’t go is to Music Row. It does however take you within reasonable walking distance.

Tip #3: Plan a morning at the free museum and Bicentennial Park

This might not be the greatest idea when it is 35 degrees in the middle of the day, but if you do get out early before the midday sun this is a decent option for getting familiar with the history of Tennessee and taking in some of downtown Nashville’s public spaces. The free bus takes you straight to Bicentennial Mall and there is a lot to see in that area, including the downtown farmers market, the free Tennessee History Museum, and the more affordable (and I heard many argue more interesting) Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum located between fourth and fifth avenues right beside the Tennessee State Capital (also something to see).

Tip #3 Plan a sunset Walk in Centennial Park

If you are content with simply seeing Music Row and not doing the Studio B tour (which is really the tip of what becomes a long line of really expensive museum exhibits), take some pictures, grab a treat from the famous Goo Goo Candy store downtown, some of the famous Hattie B’s “hot Nashville Chicken” (two locations, one that has parking a little further from downtown, and one that is hard to find parking closer to downtown) if you are so inclined,

some of the famous Hattie B’s “hot Nashville Chicken” (two locations, one that has parking a little further from downtown, and one that is hard to find parking closer to downtown) if you are so inclined, and head up to Centennial Park for a picnic and a viewing of the rather breathtaking, made to scale recreation of the Parthenon. If you never make it to Greece this might be the next best thing. And it gets more glorious in the sunset after the lights come on.

and head up to Centennial Park for a picnic and a viewing of the rather breathtaking, made to scale recreation of the Parthenon. If you never make it to Greece this might be the next best thing. And it gets more glorious in the sunset after the lights come on.

The park is free and you can walk all around it for free. But one bonus during the day is that for a small fee you can actually go inside and visit the gallery that is houses, which includes the largest statue ever made.

Tip #4: The Museums are expensive but the music itself is affordable

Take a walk down Broadway and you will realize you can take in show after show for free. And this is because most of the places where bands are playing are opened up to the street. You can waste an entire evening lingering here and enjoying the venues and not spend a dime.

Should you want to actually go in and find a seat in one of these places though, most of them do not have a cover charge, which means you only need to buy food.

Also of note is the famous Bluebird Cafe. Really hard to get in, but if you want to spend a portion of your day waiting in line (being there around 2 or 3 hours early would give you a good chance of snagging one of the unreserved spots which are first come, first serve. We were there just over 2 hours early and no one was in line yet), this is a mostly free venue where you can catch great music (with a minimum $10 per person drinks/meal along with the odd fundraiser that sometimes costs $10 or $15 per person).

Also for later nights is a place called Cafe Coco. I bring them up because they are known for good music, open late and they are a cafe, which means you can choose from a more dessert oriented menu.

http://cafecoco.com/

And it’s Nashville. It’s all about the music all the time. Research what’s going on downtown on any given evening/weekend and there is a good chance you will encounter more opportunities for free music. And if you track down where the locals like to peruse, chances are you will find an affordable evening with the best of Nashville’s music along the way as well.

Tip #5: See the Gaylord Opryland Resort for free

If you don’t really care for the high end shopping centre while you are out seeing the legendary Grand Ol’ Opry (extra tip: there is a book for sale in the Opry gift shop for $25 that essentially photo ops the entire backstage tour. If you want to take the tour but you don’t want to pay the price, linger a little bit and page through this book, or purchase it. It will make you feel like you’ve taken the tour and seen the Opry: https://www.opry.com/backstagebook), then wander over to the Gaylord Opryland Resort. Park at the far end of the mall and Opry parking lot and you will see a walkway that takes you through the wall and into the resort grounds. Follow this walkway and you will eventually arrive at the side entrance of what is a very, VERY big resort. Once you are inside, don’t be afraid of feeling like you are inside a hotel where you are not supposed to be. Keep going forward and you will enter the central plaza. This is the area, or multiple areas, that is housed by that glass dome visible from the freeway. There are maps at every entrance into this central plaza area, and you can follow the trail from there through the waterfalls, the garden, the town, etc., and it will even take you to the grand front entrance.

(extra tip: there is a book for sale in the Opry gift shop for $25 that essentially photo ops the entire backstage tour. If you want to take the tour but you don’t want to pay the price, linger a little bit and page through this book, or purchase it. It will make you feel like you’ve taken the tour and seen the Opry: https://www.opry.com/backstagebook), then wander over to the Gaylord Opryland Resort. Park at the far end of the mall and Opry parking lot and you will see a walkway that takes you through the wall and into the resort grounds. Follow this walkway and you will eventually arrive at the side entrance of what is a very, VERY big resort. Once you are inside, don’t be afraid of feeling like you are inside a hotel where you are not supposed to be. Keep going forward and you will enter the central plaza. This is the area, or multiple areas, that is housed by that glass dome visible from the freeway. There are maps at every entrance into this central plaza area, and you can follow the trail from there through the waterfalls, the garden, the town, etc., and it will even take you to the grand front entrance.

It might sound odd, but it is definitely something to see. And you can wander, stay, sit, shop, peruse as if you were actually paying the money to stay in the hotel.

https://www.marriott.com/hotels/travel/bnago-gaylord-opryland-resort-and-convention-center/?scid=bb1a189a-fec3-4d19-a255-54ba596febe2

Tip #6: Take in dinner and a movie (and maybe some pretty fantastic ice cream) in the Hillsboro Village District.

Along with The Gulch downtown (https://explorethegulch.com/) and The Arcade downtown (http://thenashvillearcade.com/) where you should track down the boiled peanuts, a Southern delicacy, Hillsboro Village is another great place beyond the downtown borders to wander and window/culture shop.

http://www.visitmusiccity.com/visitors/neighborhoods/hillsborovillage

If you are from Winnipeg, think Corydon Avenue atmosphere. And there are places to park!

The Belcourt Theatre is a great little indie theatre where you can see more independent movies and hang (and chat if you aren’t too introverted) with some of the locals. A cheap night out in Nashville. And in the area are some popular restaurants, including Fido and the Pancake Pantry (Nashville is known for their pancakes along with their hot chicken).

And highly recommended would be a stop at Jeni’s Splendid Ice-Creams, just down the block from the Belcourt Theatre.

Their cake ice cream is even gluten free, and so, so good.

https://jenis.com/

The great thing about heading to this area out of downtown as well is that it gives you an opportunity to drive through the Belmont neighbourhood, which is also where the Belmont Mansion is. Again, if you are already spent on museums and can’t spend any more, driving through the neighbourhood and by the mansion is a great Sunday drive that gives you a sense of its history.

Tip #7: Use the Greenways

If you are mobile enough to make use of the Greenways, look up Nashville’s greenway system, connecting the Opryland to downtown. It’s a cheap and affordable way to get around we well and gives you some great views of the city.

http://bikethegreenway.net/

That’s all I have for our budget trip to Nashville. I’m sure there is plenty else one could add, but for a first time to Nashville and as someone who wanted to see the big sights but not pay the big prices, these tips were a great way to feel like we got up close and personal with this beautiful, quirky, lively and very hot city without breaking the budget.

There are a lot of museums in Tennessee. And a lot of them are not cheap. In Nashville alone, two persons could easily drop more than a few hundred dollars within a couple block radius on museums.

There are a lot of museums in Tennessee. And a lot of them are not cheap. In Nashville alone, two persons could easily drop more than a few hundred dollars within a couple block radius on museums. The telling fact about this museum’s attention to detail is the scaled down replica of the Titanic that houses the exhibit itself, including the worlds largest lego Titanic.

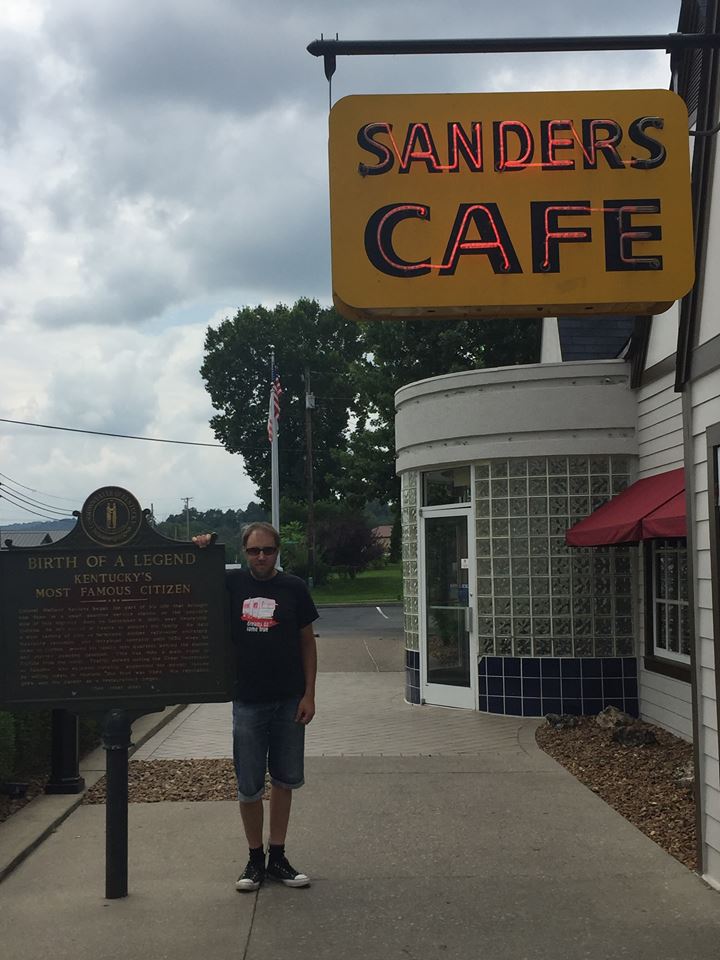

The telling fact about this museum’s attention to detail is the scaled down replica of the Titanic that houses the exhibit itself, including the worlds largest lego Titanic. Perhaps the most offsetting thing you learn about Jack Daniels (Which, as they will point out is the name of the distillery, not the drink. If you want to describe the drink it is “Jack Daniel”) is the fact that Lynchburg, the small town that houses the Distillery, is a dry town.

Perhaps the most offsetting thing you learn about Jack Daniels (Which, as they will point out is the name of the distillery, not the drink. If you want to describe the drink it is “Jack Daniel”) is the fact that Lynchburg, the small town that houses the Distillery, is a dry town.

Get close to the Mountains and talk about Moonshine, and the conversation pushes even further yet. Moonshine is the stuff of raw experience, unaged and unfiltered. The sort of drink you risked drinking and that shaped the plight of the drinker. And yet it is still Whiskey, even in its rawest form.

Get close to the Mountains and talk about Moonshine, and the conversation pushes even further yet. Moonshine is the stuff of raw experience, unaged and unfiltered. The sort of drink you risked drinking and that shaped the plight of the drinker. And yet it is still Whiskey, even in its rawest form. And the truth of all Whiskey, whether Bourbon or Jack or Moonshine, it all shares the same source, the same origin. And when it comes to the sour mash, it is akin to sour dough, with a single, seemingly eternal source giving life to endless creations.

And the truth of all Whiskey, whether Bourbon or Jack or Moonshine, it all shares the same source, the same origin. And when it comes to the sour mash, it is akin to sour dough, with a single, seemingly eternal source giving life to endless creations.

In the ancient world mountains were seen as mysterious and apprehensive places. They were obstacles to be conquered as one either fled from or journeyed toward a particular place. They were were wars were fought and they tended to be places that evoked a strong sense of fear and wonder and apprehension. They were the home of the gods as they say (which is also why they were also given the names of different gods).

In the ancient world mountains were seen as mysterious and apprehensive places. They were obstacles to be conquered as one either fled from or journeyed toward a particular place. They were were wars were fought and they tended to be places that evoked a strong sense of fear and wonder and apprehension. They were the home of the gods as they say (which is also why they were also given the names of different gods). Gatlinburg is the Mountain town that sits right outside the gates to the National Park. In earlier years it represented both a settlement for the early settlers and became an important battlefront during the civil war where the union troops that eventually settled in the area (and that remain represented today) encountered the challenge of a heavy Confederate force.

Gatlinburg is the Mountain town that sits right outside the gates to the National Park. In earlier years it represented both a settlement for the early settlers and became an important battlefront during the civil war where the union troops that eventually settled in the area (and that remain represented today) encountered the challenge of a heavy Confederate force. Pigeon Forge by contrast holds the remnants of the areas industrial roots, being built around this old iron forge that eventually was shut down and turned into an old mill that is still functioning today.

Pigeon Forge by contrast holds the remnants of the areas industrial roots, being built around this old iron forge that eventually was shut down and turned into an old mill that is still functioning today.

, dot the interstate itself.

, dot the interstate itself.

Now mere remnants of a failed dream, Lafayette used to be an epicentre for the longest canal ever built in North America, the Wabash and Erie Canal that closed after operating only for about a decade. It becomes a bit of a treasure hunt to track down traces of the old canal these days, but one of those places is a restored 10 mile historic section of canal trail that connects to Delphi along the Wabashi river, a short drive from Lafayatte. You can even take a wonderfully quaint canal ride on a restored canal boat or walk the trails to gain a glimpse of the canal’s grand past.

Now mere remnants of a failed dream, Lafayette used to be an epicentre for the longest canal ever built in North America, the Wabash and Erie Canal that closed after operating only for about a decade. It becomes a bit of a treasure hunt to track down traces of the old canal these days, but one of those places is a restored 10 mile historic section of canal trail that connects to Delphi along the Wabashi river, a short drive from Lafayatte. You can even take a wonderfully quaint canal ride on a restored canal boat or walk the trails to gain a glimpse of the canal’s grand past.

(Picture from Indianapolis monthly of the Indeanapolis Canal)

(Picture from Indianapolis monthly of the Indeanapolis Canal) But it was our missing our 164 East exit, which would have veered us directly away from downtown Louisville, that offered us a spectacular up close and personal view of the park, the skyline and the Big Four Bridge (a joint effort to connect the Indiana/Kentucky state line which is divided by the river) right before looping us back through the heart of downtown in order to get us heading back East.

But it was our missing our 164 East exit, which would have veered us directly away from downtown Louisville, that offered us a spectacular up close and personal view of the park, the skyline and the Big Four Bridge (a joint effort to connect the Indiana/Kentucky state line which is divided by the river) right before looping us back through the heart of downtown in order to get us heading back East.

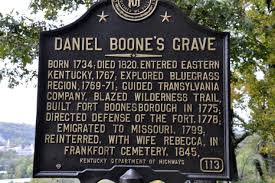

His story has developed into a legend that appears to serve both sides of a competing political view, on one hand as an icon and symbol of conquest and Western expansion who is depicted brutally scalping and murdering the “savages” threatening their progress and their lives, while on the other hand representing someone who shunned images of early American civilization and development by removing himself from these areas and establishing positive relationships with the indigenous people in a life lived isolated from the ignorance of the cities themselves.

His story has developed into a legend that appears to serve both sides of a competing political view, on one hand as an icon and symbol of conquest and Western expansion who is depicted brutally scalping and murdering the “savages” threatening their progress and their lives, while on the other hand representing someone who shunned images of early American civilization and development by removing himself from these areas and establishing positive relationships with the indigenous people in a life lived isolated from the ignorance of the cities themselves.

, noting it as the home of the “world’s best” gummi bear (of which I can now attest).

, noting it as the home of the “world’s best” gummi bear (of which I can now attest).

Which is simply to say, dreams are made of both the highs and the lows. Dreams are made of both excitement and fear. And what I realized is that rather than make me cynical, this truth should give me reason to be grateful. Because if there is one constant in the high’s and low’s it is this- stepping out into our dreams helps build a foundation. It gives us a place to start from and a means of moving forward. It teaches us something important about the present moment while offering us something to invest in for whatever our future dreams might become. It shapes our voice and give us a way to speak above (and through) the noise of the everyday. It allows us to embrace and not miss the joy and deal with the disappointment.

Which is simply to say, dreams are made of both the highs and the lows. Dreams are made of both excitement and fear. And what I realized is that rather than make me cynical, this truth should give me reason to be grateful. Because if there is one constant in the high’s and low’s it is this- stepping out into our dreams helps build a foundation. It gives us a place to start from and a means of moving forward. It teaches us something important about the present moment while offering us something to invest in for whatever our future dreams might become. It shapes our voice and give us a way to speak above (and through) the noise of the everyday. It allows us to embrace and not miss the joy and deal with the disappointment.

It captures the power of the unexpected, and it is the ability to wonder what lies behind the next bend or the next corner that awakens us to the joy of being a kid that the film wishes to express and celebrate.

It captures the power of the unexpected, and it is the ability to wonder what lies behind the next bend or the next corner that awakens us to the joy of being a kid that the film wishes to express and celebrate.

And I imagined her meeting a Bobby, played with an unrelenting compassion by the talented Willem Dafoe, someone who could tell her that no matter what the world told her that she had a place to belong. And I imagined her putting on her dress and running through the gates of Disney World to celebrate with the children on the other side of that divided line regardless of her slightly run down house, ethnicity or neighbourhood stereotype. And I turned from my imagination to offer up a prayer. A prayer that this little girl might never lose that sense of joy. That she would aspire to be a Moonee. A prayer that the next time my own actions needed to speak louder than my words that I would chose to do more than simply ignore it. That I would aspire to be a Bobby.

And I imagined her meeting a Bobby, played with an unrelenting compassion by the talented Willem Dafoe, someone who could tell her that no matter what the world told her that she had a place to belong. And I imagined her putting on her dress and running through the gates of Disney World to celebrate with the children on the other side of that divided line regardless of her slightly run down house, ethnicity or neighbourhood stereotype. And I turned from my imagination to offer up a prayer. A prayer that this little girl might never lose that sense of joy. That she would aspire to be a Moonee. A prayer that the next time my own actions needed to speak louder than my words that I would chose to do more than simply ignore it. That I would aspire to be a Bobby.

Harnessing and Setting the Tone – Creating a True True Mash-up of everything that is good and right about the MCU

Harnessing and Setting the Tone – Creating a True True Mash-up of everything that is good and right about the MCU

Take the opening scene for example. We are thrown into the harsh reality of genocide. This flows straight out of the story of Ragnarok and connects us to the world of the Guardians, the old and the new being brought together through a single picture of desolation. And it is out of this that the film is able to dig into the personal stories of Star Lord, Stark, Thor and Rocket revealing a shared experience on an even deeper and more personal level even though these characters have just met for the first time.

Take the opening scene for example. We are thrown into the harsh reality of genocide. This flows straight out of the story of Ragnarok and connects us to the world of the Guardians, the old and the new being brought together through a single picture of desolation. And it is out of this that the film is able to dig into the personal stories of Star Lord, Stark, Thor and Rocket revealing a shared experience on an even deeper and more personal level even though these characters have just met for the first time. The film uses this as a entry point into the relationship between Stark and Dr. Strange, bridging the mysticism of Strange with the concrete, scientific methods of Stark and connecting it to their need to control (or their inability to control) what is happening and their burgeoning desire to each make a difference and be a difference maker in their own way, or in the case of Stark to leave a legacy that will last beyond his aging presence in these films.

The film uses this as a entry point into the relationship between Stark and Dr. Strange, bridging the mysticism of Strange with the concrete, scientific methods of Stark and connecting it to their need to control (or their inability to control) what is happening and their burgeoning desire to each make a difference and be a difference maker in their own way, or in the case of Stark to leave a legacy that will last beyond his aging presence in these films. The True Story of the Greatest Villain

The True Story of the Greatest Villain

For Thanos, the only way he saves the world is by sacrificing Gomorah, through which we are given a striking picture of this moral ambiguity. Where Thanos stands on the right or wrong side of this line isn’t always clear and throughout the movie we are left to struggle with where his motivation lies, for self or for others. All we really know is that all of this death, all of this loss, all of this destruction is painful and not the way things are supposed to be.

For Thanos, the only way he saves the world is by sacrificing Gomorah, through which we are given a striking picture of this moral ambiguity. Where Thanos stands on the right or wrong side of this line isn’t always clear and throughout the movie we are left to struggle with where his motivation lies, for self or for others. All we really know is that all of this death, all of this loss, all of this destruction is painful and not the way things are supposed to be.

Disassembled Hero’s Assemble

Disassembled Hero’s Assemble