The last time I remember spending quality time in the book of Ecclesiastes I was working as a Youth Pastor for a Lutheran Church. The funny thing is, when I was hired as Youth Pastor it was my first time stepping through the doors of a Lutheran Church. So I had a lot to learn, especially when it came to getting my head around the liturgy and the traditions. I also learned that Lutherans love to sit around and have long talks about theology… a lot of long talks. My dream job!

When I think back to those years, some of my most memorable discussions happened around a series I was asked to do on the book of Ecclesiastes. And if there was one thing I took away from these discussions, it is that the themes in this book have a powerful way of digging underneath the surface and getting very, very personal very, very quickly in ways that other topics might not. Which tells me this is a challenging book not just to teach, but to read, to study, to meditate on. A challenging book for many people for many different reasons. And I think, if I could take my best guess, this it at least partially because the book has a way of exposing the things we bring to our reading of the text out of the particular places we find ourselves on this journey called life, most notably our fears and our anxieties about matters of faith and matters of doubt.

Making Sense of Life and Death

When I was preparing to speak on Ecclesiastes this time around, an old cartoon came to mind:

The more time I spend in Ecclesiastes, the funnier this cartoon gets. And truth be told, this is how I tend to picture the teacher of Ecclesiastes in my mind. Sitting up in his bed and thinking about life and death, struggling to figure out what it all means. The teacher is on a journey, having grown old and left to ponder the worth of his life. So we get everything, the good the bad and the ugly of this candid reflection. This also means we find contradictions of course, reflections that we see changing and overlapping from one moment to the next as he tries to weigh his experiences and struggles through the lens of a complicated ancient world (and in truth, Ecclesiastes ends up as a hard book to categorize, especially as it tries to fit into the OT canon and the wisdom tradition). In an effort to find meaning and purpose, the teacher offers us a very intimate portrayal of what is a very personal and very human struggle, on one hand finding solace in things like work and rest, merriment and relationship, while on the other seemingly haunted by the idea that even these sort of temporary joys remain allusive and finite.

The Little Prince and The Search For Meaning

I have written elsewhere in this space about this film, but “The Little Prince”, based on the novel by French writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, had much to add to my own reflections on Ecclesiastes, especially when it comes to fleshing out this very human struggle. It tells the story of an aging Aviator, who is searching for someone to share his story with, and his growing friendship with a little girl who lives next door, a girl who ends up, after facing the vanity in her own life, wanting to help him find the right ending to his story, the one she believes would be more just. The story that the Aviator wants to share is the story of the little Prince and his rose who both live on one of many asteroids in the sky (the stars that the Aviator and the little girl look up at and admire). The Prince forms a relationship with this rose but eventually becomes distracted by the promises of the world around him. He decides to forget about the rose and heads out to explore the other asteroids in the universe. As he does this, we come to discover that each of these asteroids represents one of the many places in which we tend to find our identity in this world of ours- admiration, success, money, work.

In a similar way, the teacher in Ecclesiastes is searching for wisdom. He writes, “Yet when I surveyed all that my hands had done and what I had failed to achieve, everything was meaningless, a chasing after the wind. Nothing was gained under the sun.” (2:11)

And so he record his thoughts, saying, “I devoted myself to study and to explore by wisdom all that is done under the sun.

A note about the phrase “under the sun”. It is mentioned over 30 times in this book. It is an all encompassing phrase that depicts a sun rise and a sun set, the days of our life measured and counted.

And what does the teacher find when he studies all that is done under the sun?

“What a heavy burden God has placed on humankind.” 1”13.

No wonder Charlie Brown can’t sleep.

Looking Between the Bookends: The Search For Meaning

Just to reinforce this idea, a further word on the structure of the book itself. Ch1 and Ch 12 act as bookends, told from a Narrators perspective, which hold together the words, or the searching of the teacher that makes up the body of this work. These bookends are marked by the phrase vanity of vanities, all is vanity, or all is meaningless.

In this light, the recognition that life is meaningless, the vanity of it all, becomes the starting point towards the books final word, the conclusion of how, and if, God fits into this whole discussion as a sacred text. And as one commentator (Donald Berry) puts it, this starting point moves us through 3 essential crisis of faith (or meaning) that the teacher sees as the root of this very human struggle, this wrestling with the vanity of it all:

1. Ignorance of the ultimate, or those big questions surrounding who God is, where He is and why He does what He does.

2. The sense of life’s injustice, that in looking at the world around us life is inherently unfair.

3. And a perceived lack of gain or reward for our actions and effort, the fact that for as much as we try and try and try again, this world, and our life, still spins outside of our control.

And as readers, as we move through this book, we become aware of these three crisis of faith through the realization that there is nothing new under the sun (1:9), the limitations of self indulgence, hard work and even wisdom to truly define us in chapter 2. The plight of the oppressed and oppression in this world in chapter 4. Envy, lonliness, worry, the foolishness of our actions all come up as the Teacher also considers the inability of material possession, wealth and status to bring us true joy and satisfaction.

And so the sun rises, the sun sets, we get older and death eventually has its way, with all of these temporary and finite sources of identity and purpose eventually fading away with into the vanity of it all.

Here we arrive at the true challenge of learning how to read this book well- to know how to move from this place, the vanity of it all, to the idea of a God who gives this heavy burden, this persisting sense of vanity, meaning.

And this challenge exists both in understanding the authors intent or purpose for writing this book, but also for understanding who we are as readers and hearers of the text. Here the teacher assumes that we are either aware or we remain unaware of the vanity that he observes, struggling with or choosing to deny the struggle. And (he) is convinced that for us to move towards the God of 3:11, who it says is making all things beautiful in His time, the same God who resurfaces again in the final chapter (12) as the book pushes towards its conclusion, the result of its searching, we must learn how to face this vanity, this sense of meaninglessness, head on. And the result of facing this vanity? Here, after all has been measured, after all has been considered, is the end of the matter: Fear God and keep His commandments, for this is the whole duty of humankind.

And here is something I have found important for my own study of these final words: Fear God does not arrive as an alternative to all the vanity, all the meaninglessness. Rather, it is the end result, the conclusion of this grand experiment called life, this search for wisdom that has consumed the teacher, the result of wrestling with the uncertainties of life instead of running away.

A line in The Little Prince puts it this way. “What makes the desert beautiful, is that somewhere it hides a well.”

Fear God: A Complicated Notion

So what does this phrase actually mean, practically speaking, this call to fear God? I have struggled with this phrase for a while now. I think the first clue we get though is found in the “for” statement that follows:

“For God will bring everything into judgment, every secret and unknowable thing regardless of good or evil.”

If life is simply a roll of the dice. If the way the cards fall is less than fair or just or forgiving when we take a long and searching look at the state of our world, then it is the judgment of God that arrives not as a defeatist notion or condemnation, but rather as a source of life, a judgment that breathes hope into our reality, a renewed sense of purpose. It is in this sense of hope, this renewed sense of purpose that we find unconditional love, forgiveness, and grace. These are the things, the teacher believes, are the things that can help us make sense of this world, of the question of God. We begin with vanity, but the vanity opens us up to our need for God.

In all Things “God”

The words “all, whole, every” in chapter 12, and through the whole of the book, carry a certain force in this text. They tell us that God is source of everything and everything belongs to God. And when all else fades away, as the book insists it will, God will remain.

And here is the amazing thing. if this is true, if this something we can truly trust and give our lives towards, then this means we also belong to God, the God who is making something beautiful out of the mess, out of the tragedies, out of the brokenness, in the midst of so much hurt and pain in this world that surrounds us every, single day. And this truth arrives not in our moments of certainty and clarity, but in the places of our uncertainty, in the unknowable, n our limitations, and in our lack of control over taming the evils, the injustices that we see in this world.

Yes, this book recognizes that the feeling of vanity, of meaninglessness might not always feel welcome. It never feels welcome actually. But the teacher reminds us that the vanity represents an opportunity to see God at work and to learn what it means to trust Him even when we can’t know or see what’s ahead. The teacher reminds us that where we cannot control the evils and injustices in this world, in faith God is able to use us as agents of hope of something better, something meaningful.

And here’s the thing. I think the whole point of Ecclesiastes, of the Teacher’s reflections, is to teach us how to position our lives in such a way as to “consider” the work of God in a world that often seeks to blind us to it so that we can then be God’s hands and feet in this world, God’s presence and voice in the meaninglessness.

From Vanity To Grace

In the film The Little Prince, as the Prince goes from asteroid to asteroid searching out the universe, eventually he comes to the same realization as the teacher. All is vanity. And while he has long forgotten his relationship with the rose, eventually he remembers the value that the rose gave his life. And so he desires to return, to fin this rose again, only now he fears he has wandered too far, and that there is not enough grace in the world to help him find that rose again.

In one particular scene in the movie, we find the Aviator and the little girl lying in the grass and staring up at the stars imagining the lessons of the Little Prince for their own lives as they consider their own discontent with the world around them. The Little girl laments having to grow up, to grow older, to which the Aviator says, “Growing up is not the problem, forgetting is.”

Learning to Remember

If all of this seems a bit lofty or difficult, or even too theological, we also arrive at a final, very practical piece of wisdom in the opening verses of chapter 12 that can help us make sense of what it means to Fear God in our day to day life. This is the same advice that the aging Aviator gives the little girl, now coming from the mouth of the Teacher: “Remember” the teacher says. “Remember your creator.”

And while this passage speaks about remembering “in the days of our youth”, I think it more accurately supposes a concern for the present, regardless of age. What I hear in these words is a sentiment to never stop remembering regardless of how old we are, to not let the stuff of growing up cause us to forget who we are as a reflection of God’s work, God’s grace. If you are 7, remember. If you are 70, remember. It is never too early or too late to remember your Creator. Because it is this act of remembering, this act of positioning ourselves so as to see God in the vanity, that remain our source of life and hope and meaning in our final breathe.

My Story

On this same practical note, this verse is an important one for me in my own life. Sometimes I am very protective of this story. Sometimes I feel the need to share it, usually to remind myself of what it means in my life. It is a story that fits with the text of Ecclesiastes and the words of the Teacher. It comes at a very tough time in my life, a time when I was wrestling with many of the questions of Ecclesiastes and when circumstances had kind of left me bare and wondering who I was. One particularly tough night everything kind of came together in a perfect storm. I remember laying in my bed much like Charlie Brown and thinking about life and death. I was at the end of my rope, struggling with suicidal thoughts. And in that moment I had a very direct conversation with God. I asked him to give me something, anything, to hold on to. I made it through the night. The next morning I went on my way. I was broken on the inside, but still doing life on the outside. I was very involved at my local Church. And this day I was heading out to meet with someone at the Church for something completely unrelated. When I got there, there also happened to be someone else there, a third party who at one point eventually asked to pray for me. I said yes and they prayed for me. This prayer ended up catching me off guard, as this person, whom I did not know and did not know my situation, ended up recounting my conversation with God the night before. As it turns out, they had been praying earlier that afternoon and God had given them words to say specifically to me, words that I call my Letter from God.

This letter said a few things, but the thing I remember most are the words “remember”. Remember back to a time when your faith was strong. Remember back to a time when I expected God to work in my life.

And so from this time forward I began to give myself over to this remembering process. I built into my life a practice of self reflection. I went through my old photos and old letters. I spent time thinking back over memories of my life. And what I found is, the more I looked the more I saw God working in ways I had long since forgotten. In more recent years, I started a blog, following my 40th birthday actually, so that I could (and can) keep reflecting and keep remembering through the written word. My 40th year was a really tough one for me to be honest, and it kind of rekindled some of that encounter with God all those years ago. It gave me my first real sense of growing old, of the kind of loss that comes with growing old. And I had the feeling this loss was only going to grow harder and harder from here on in. And so I continue the journey, continue the search, wrestling through the vanity to try and see God, and to allow God to infuse this vanity with a sense of joy, a sense of purpose.

The Strength of Aging Well

I found myself in a discussion with my brother and my sister in law recently while I was working my way through Ecclesiastes. They are both connected to the field of social work and social services. After having read through and reflected on Ecclesiastes in preparation for this, I came away with the thought that, man, it has a really negative view of aging. Getting old, according to the Teacher, seems like it is really going to suck. So enjoy life while I have it.

My brother and sister in law said something to me that caused me to go back and read through the book again with a different perspective. They were talking about long term care homes and the struggle of seniors in these homes. They said the number one problem that seniors face in these places is depression. There is a loss of identity that is very real for them, a sense that they no longer matter or are needed in this world. That they have nothing left to contribute. And sadly this is something that many people my age (and younger) tend to perpetuate. The truth is, after all, that life has a way of swooping in and stealing our faith, stealing our sense of meaning, of God, of what matters. And we can try and try and try and give ourselves to creating the best life possible, but in the end it is out of our control, just like the powerful montage in the movie UP that shows an aging man coming to terms with the cruel realities of this world, a reality that leaves him shutting himself away from the world and giving into his own sense of misery and grief.

And yet, their (my brother and sister in law) conviction was that there is a really simple solution to the problem- social activity. Social interaction. This is the same thing that we see in the movie UP, a friendship giving the aging man a reason to come out of his house, to face the world and to go on living. Giving the aging population the opportunity to contribute to society on a daily basis. They brought up statistics. The aging population today has much to offer still. They are the ones (not all, but many) who are known for saving, for having worked long hours and building the sort of ethic that has much to give to our economy, to our society. My generation (and younger), statistically speaking, is not great at saving, has not had a lifetime to accumulate, and is known for having gone through multiple careers before we have even reached 25. We (and they) are known for contributing in other ways.

Two generations that live very differently, and yet the one thing we share is the one thing that is a big part of the solution- time. We have time to give and the aging population needs our time, something I have neglected in my own life. And in the view of the teacher, time is what we have in the present, however fleeting it will eventually become.

It’s kind of funny. The last time I spent time in Ecclesiastes I was a good deal younger than I am now. Having moved away from years on the assembly line doing wharehouse work, I was still a bit stuck in a mindset that tended to look at aging with a lot cynicism. In the wharehouse you fell into one of two categories- you were either young or you were considered a lifer. And we often argued about where the line was, that point of no return when you become too old to leave. And the assumption was this- young means the opportunity to make something of yourself. Old means it’s too late to be something meaningful. And those of us who were young used to look down on the lifers.

But then I started to get older myself. And I realized how much my young self didn’t know. How little I could really depend on those ambitions, those opportunities that I assumed gave worth to my youth.

I bring this up to say, when I considered this conversation with my brother and my sister in law in the light of Ecclesiastes, I found myself reading back through the text and discovering that the text actually presupposes the value of aging. Yes, there is much that aging steals away from us and much that we can rightly grieve. But this call of the teacher to fear God, to consider the work of God, to remember our creator, is a practice that no only allows us to age well, but a practice that gains that much more worth in the text the older we get. The call to remember our Creator in this text is not so that we remember while we are young and forget when we are older. It is so that when we grow up, when we grow older, the vanity doesn’t steal our vision of the God who is carrying us forward, who is the source of our meaning. And here is what I missed on that assembly line all those years ago. How amazing is it to find a witness of faith in someone who is 80, someone who has experienced and face the vanity head on and still managed to say, I trust God with all my life, all my heart. And how much empathy did I need to give myself as I fail to do that (in so many ways) as I cross that dreaded 40 marker. And instead of fearing becoming a lifer, I wish I would had known what it meant to fear God instead.

If I have something to offer to those who are young, it would be that I never knew back then how much I would need the voices of the aging and the experienced in my life, voices that made the decision to remember their creator. And I feel shame over the fact that I neglected what I could also give to the aging as well, those who might be struggling to remember their creator in the midst of the vanity of life.

But as the text says- grace. Remember your creator in the present. Do the work of fearing God today. And for me, I see an importunity to invest in the live of the young people in my own place or work, and perhaps to push myself to sit and listen with those who are older than me.

Learning to See the World Again

“The world conspires to make us blind to its own workings; our real work is to see the world again.”

– Adam Gopnik (in his commentary on The Little Prince)

This is where the teacher leaves us, with the work of seeing God again, of seeing the world from His perspective. If there is a final message to the film, The Little Prince, it would be that it is in community that our commonness becomes uniqueness. It is when I learn the name of my neighbour and hear their story that they, and I, become distinguishable, are given meaning. The Little Prince learns this when he finally remembers and considers the value of the Rose. The Aviator learns this when he finds friendship with this little girl, one who is wiling to hear his story. And the girl finds this when she is forced to face the ending of the Aviators story, something that reminds her of the worth she has in her own.

And in the same way, in our communion with God, our shared struggles, our wrestling with the vanity, whatever that may be, becomes a personal expression of God’s grace, a grace that then is able to extend meaning to the world around us as well. And as Christians, we have the ultimate expression of this communion in the coming advent season. The celebration of the most practical examples of God’s work in our lives and our world- Jesus. In Jesus God chooses to enter into the vanity and the meaninglessness in order to share in our struggle. And in this sharing we find our meaning, we are given meaning.

And here is the truth this offers to us as ones who trust in what we cannot always know, what we cannot always see. God is okay with the mess. God is okay with us trying to make sense of him from the places that we find ourselves, however uncertain those places might be.

Merest Breathe, All is Merest Breathe

As a closing word, one commentator that I read left me with a word that I found very helpful. The word “vanity” is what the indicates breathe. And in translation it can move between two meanings. One indicates the fleeting sense of “breathe”, the vanity. The other is life giving, the breathe, or the exhale of the spirit of God Himself. This commentator suggested that maybe the text is better translated as “merest breathe, all is merest breathe”, a picture of God exhaling his spirit over our struggle, our finite efforts. And in translating it this way, maybe there is a picture here of God breathing life into the emptiness, of breathing meaning into vanity. I think this fits with the teachers own conclusion of his search, his journey. When all else fails, as he would insist, God remains. And it is in God that we find our true identity. Amen.

Coco and The Contextualization of Family

Coco and The Contextualization of Family By the end of the film we see these two competing forces come together through a resonating message that, however messy family can get it is also the context in which we are able to learn forgiveness, grace, and the merits of unconditional love, all of the things necessary for belonging. For Coco (and the Mexican tradition it brings to light), the call to “remember” ones family is not necessarily about narrowing our perception of the places to which we belong, but it is about the opportunity to envision these acts of forgiveness, grace and love into our personal context. But in a world as vast and as colourful and as intricate as the one Coco illustrates for us on screen, it also operates as a stark reminder of just how quickly theses things can become lost when our vision of family becomes too narrow, when the family structure and name becomes our idol, the means by which “we” belong (somewhere) rather than the model for how we relate to and include the “world”.

By the end of the film we see these two competing forces come together through a resonating message that, however messy family can get it is also the context in which we are able to learn forgiveness, grace, and the merits of unconditional love, all of the things necessary for belonging. For Coco (and the Mexican tradition it brings to light), the call to “remember” ones family is not necessarily about narrowing our perception of the places to which we belong, but it is about the opportunity to envision these acts of forgiveness, grace and love into our personal context. But in a world as vast and as colourful and as intricate as the one Coco illustrates for us on screen, it also operates as a stark reminder of just how quickly theses things can become lost when our vision of family becomes too narrow, when the family structure and name becomes our idol, the means by which “we” belong (somewhere) rather than the model for how we relate to and include the “world”.

And when I do it causes me to miss who this kid really is in the process, in a given moment. It also, and this perhaps the greatest struggle, causes me to miss what this kid actually needs in the process, in a given moment.

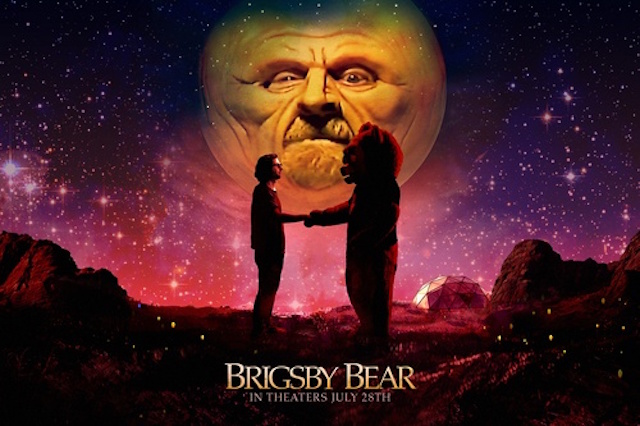

And when I do it causes me to miss who this kid really is in the process, in a given moment. It also, and this perhaps the greatest struggle, causes me to miss what this kid actually needs in the process, in a given moment. There has been little tougher for me than allowing my son the freedom to wrestle with his memories of his birth parents and celebrating his memories of life in the orphanage. Because as a parent it just makes me angry to consider what he had to endure in such a brief amount of years. But for him it is important. It is necessary. It is life giving even. And the film does a masterful job at juxtaposing the world of James’ isolation against his emergence into the world he is now coming to discover. For years he had been raised on episodes of Brigsby Bear where the imagination of these childhood images ended up mixing with subtle and confusing messages that had fostered empathy for his captors, for the world that had been handed to him. We catch glimpses in this show within a show of strange phrases such as “Prophecy is meaningless. Trust only your familial unit”, or “curiosity is an unnatural emotion!” These are phrases meant to instil in him a sense of compassion for the world that has kept him safe and fear for the world outside that might or could infringe on this sense of safety. And a part of the process for him as he remerges back into the world is figuring out how to come to terms with what is real and what is not, what is the truth and what are the lies that he has been told, and perhaps most significantly which emotions he can actually trust when it comes to what is good and what is bad in his mind.

There has been little tougher for me than allowing my son the freedom to wrestle with his memories of his birth parents and celebrating his memories of life in the orphanage. Because as a parent it just makes me angry to consider what he had to endure in such a brief amount of years. But for him it is important. It is necessary. It is life giving even. And the film does a masterful job at juxtaposing the world of James’ isolation against his emergence into the world he is now coming to discover. For years he had been raised on episodes of Brigsby Bear where the imagination of these childhood images ended up mixing with subtle and confusing messages that had fostered empathy for his captors, for the world that had been handed to him. We catch glimpses in this show within a show of strange phrases such as “Prophecy is meaningless. Trust only your familial unit”, or “curiosity is an unnatural emotion!” These are phrases meant to instil in him a sense of compassion for the world that has kept him safe and fear for the world outside that might or could infringe on this sense of safety. And a part of the process for him as he remerges back into the world is figuring out how to come to terms with what is real and what is not, what is the truth and what are the lies that he has been told, and perhaps most significantly which emotions he can actually trust when it comes to what is good and what is bad in his mind.